After the Japanese military attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, the U.S. government began forcibly removing Japanese Americans from the West Coast and relocating them to isolated, inland areas. Around 120,000 people were detained in internment camps for the remainder of WWII. Among those interned were various artists – some were professional artists, some created works of art or crafts to occupy their time, and others used art to document their experiences during this uncertain time.

Chiura Obata, a notable artist and art teacher, was one such detained Japanese American artist. Last month, the Utah Museum of Fine Arts (UMFA) acquired thirty-five of Obata’s works created between 1934-1943, many of which were created during his internment in Utah.

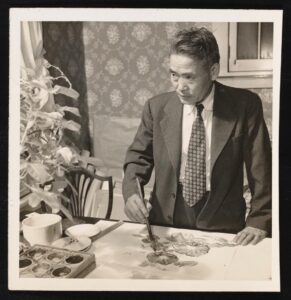

Copyright: Archives of American Art, Chiura Obata Papers

Obata was a California-based artist who emigrated to the United States from Japan in 1903. After gaining notoriety early in his art career, Obata was named as a faculty member of the Art Department at the University of California, where he worked from 1932-1954. However, in the wake of the Pearl Harbor attacks, Obata and his family were relocated from their California home and interned. They were first sent to the Tanforan Detention Center (located in the Bay Area) and then to the Topaz War Relocation Center in Utah.

During his internment at each detention center, Obata served as a leader in creating art schools for detainees like himself. In addition to teaching, Obata created some 350 works during this period. These works included large-scale paintings of the landscapes surrounding the camps, drawings for the camp’s newspaper, and watercolors and sketches that documented life as a detainee (given that cameras were not permitted, artworks were used to create a record of daily life). Obata wished to show that he and his countrymen had not been defeated by the prejudice and humiliations they suffered.

Today, Obata is known for his brush and ink landscapes and portraits of America, in which he blends traditional Japanese brush styles with traditional Western techniques. Despite his time in the camps, Obata’s work shows a fascination with and focus on the rugged beauty of American landscapes, at odds with the ugliness of the detainment centers. He was able to find “the beauty that exists in enormous darkness.” The collection at the UMFA was donated by the Obata Estate. Representatives of the estate hope that “people will be inspired to learn the history of wartime incarceration and go visit the actual camp site in Delta as well as the Topaz Museum,” after viewing the pieces at the UMFA.

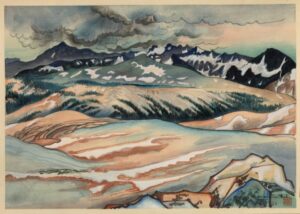

Chiura Obata, Great Nature, Storm on Mount Lyell from Johnson Peak, 1930, color woodcut on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Obata Family, 2000.76.8

Copyright: Lillian Yuri Kodani, 1989

In addition to this new collection, Obata has been featured in several exhibits and his works are in the permanent collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, the Smithsonian, and other well-known institutions.

Art created during this period of internment, however, went beyond Obata’s contributions. Many Japanese Americans had been artists previously or found solace in art during this period. George Matsusaburo Hibi was another notable artist interned with Obata. The two men worked together while at the Tanforan Assembly Center to create an art school, which eventually enrolled 600 students.

Before internment, Hibi was a student at the California School of Fine Arts. Throughout the 1930s, Hibi’s work was exhibited in the San Francisco area, and was even exhibited at the Oakland Art Gallery in 1943 while he was still interned in the camps. Hibi is primarily known for his printmaking and oil paintings. Many of his works depict the bleak aspects of the camp, including the harsh winters.

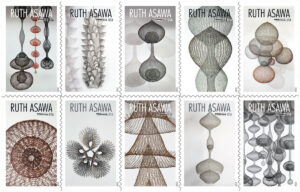

2020 Stamps honoring featuring Ruth Asawa’s art. Copyright: 2020 U.S. Postal Service.

Other notable interned artists were ones that worked as animators for Walt Disney Studios, including Tom Okamoto, Chris Ishii and James Tanaka. Like Hibi and Obata, these cartoonists also used their time at the internment camps to teach art. One of their students was Ruth Asawa, a young girl who had not previously explored art. While interned, however, she found free time to draw and explore her creative talents. Today, Asawa is a renowned artist with works in the Guggenheim Museum and the Whitney Museum in New York. She is known for her wire sculptures and the fountains she was commissioned to create in San Francisco. In 2020, the U.S. Postal Service honored her by featuring her art on a series of stamps.

During WWII, American Japanese internment camps were not the only camps that detained artists. In Nazi Germany, millions of people were forcibly interned. The circumstances and treatment of the prisoners at these camps varied, but in some cases, they were significantly crueler and more repressive. Unlike the U.S. internment camps, many Nazi camps were a mechanism to kill people. However, like the U.S. internment camps, they provided an unlikely source of inspiration and solace.

One famous artist who emerged from the camps was Kurt Schwitters. Schwitters had had gained renown as an artist for his involvement in the Dada movement, but in 1940 he was placed in a camp on the Isle of Man. Like the interned Japanese American artists on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, Schwitters created art in a studio and used his time to teach other prisoners, some of which became successful artists in their own right. However, creating and teaching art were not easy for Schwitters. Given the circumstances in the camps, art supplies were scarce. This forced Schwitters and other artists to become resourceful and find alternate tools to create art. People at the camp with Schwitters recall that he pulled up the linoleum flooring to paint on and even made a sculpture out of his porridge. Regardless of these obstacles, Schwitters produced over 200 works while at the camp. To honor these works and Schwitters’ legacy, a gallery near where he was interned exhibited his work. It attracted thousands of visitors in 2013.

Other works by imprisoned artists are honored at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum. The Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum is located at the site of the site of the former concentration camp and has a gallery with over 2,000 works of art that were created by prisoners at the various Nazi camps. In some of the more restrictive Nazi camps, art and any tools needed to create art were forbidden. Rather, works created in these camps were prepared in secret and using whatever supplies detainees could find. Many of the works were created to defy the Nazis and expose and document the atrocities occurring in the camps.

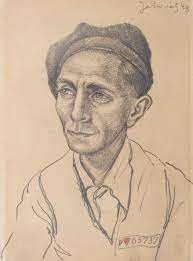

Drawing by Franciszek Jaźwiecki

Photo Credit: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum

Famously, Polish artist Franciszek Jaźwiecki secretly created a historical record through his portraits. An art historian at the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum believes that he drew these portraits for the purpose of creating a historical record, given that he included the prisoners’ numbers in each of his portraits. This has allowed historians to attach a name to the portraits through the number. Jaźwiecki took a huge risk by creating these drawings, as it was strictly prohibited. Records reveal that he hid his portraits in his bed or in his clothes. The portraits survived and after his death, his family donated 100 of his works to the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum in remembrance of his experience.

Many other such works and photographs have been uncovered. Historians believe that, like Jaźwiecki’s portraits, they were being used to document the people, conditions, and events in the camps. On display at the museum is a sketchbook with 22 pictures by an unknown artist. During his time at Auschwitz, he secretly drew the exterminations of detainees. His drawings were found in 1947 in a bottle that had been hidden in the foundations of a building near Birkenau’s crematoriums. This sketchbook is the only artwork uncovered that documents the extermination at Birkenau.

While internment camps are a difficult part of history, the art that was produced there reflects and documents this era. Art was both a practical tool for prisoners to occupy their time, but also contribute to newsletters and document the people and circumstances of the camps. It was additionally an emotional tool to help prisoners distract from their realities, retain their identity and purpose, and in many cases, to expose and cope with the bleak environments in which they were detained.