Museums across Europe and the United States were poised to commemorate the 500th anniversary of Raphael’s death with spectacular exhibitions dedicated to the Renaissance master. Born in Urbino, and sometimes referred to as il Divino (“the Divine One”), Raffaello Sanzio died at the young age of 37. During his short lifetime, he produced gracefully elegant works that changed the course of art history. This year’s exhibitions may no longer be accessible to visitors due to COVID-19, but we are pleased to present this guest blog post focusing on the provenance of one of the great master’s missing works, Portrait of a Youth. The blog post was submitted by Julia Pacewicz, detailing her research on the work. With a degree in art history from New York University, Julia is currently studying Heritage & Memory at the University of Amsterdam. Prior to beginning her graduate studies, Julia worked as a cataloguer at Paddle8 and Sotheby’s.

In May 1945, American soldiers arrived at the residence of Hans Frank in the Bavarian countryside. There they recovered a wooden chest where two Rembrandts, one da Vinci, and several other paintings lay hidden. The end of World War II marked the beginning of decades-long investigations for Nazi looted art. Prior to the start of the war,Raphael’s Portrait of a Youth, along with Rembrandt’s Landscape with a Good Samaritan and da Vinci’s Lady with Ermine, decorated the walls of Czartoryski Museum in Kraków, Poland. But to this day, Portrait of a Youth remains missing.

My aim is to present to you a case study detailing the story of one of history’s most intriguing paintings. The provenance research below is divided into two components. The first part unearths part of the history prior to the earliest confirmed modern owner (the Czartoryski Family), with the ultimate goal of identifying the lineage of the painting as well as the sitter; the second part focuses on retracing the painting’s movements during the Second World War, with the hopes of bringing us closer to where the painting resides today.

The oil on poplar wood painting is commonly attributed to the great Italian Renaissance master, Raffaello Santi (also known as Raphael). The portrayal of the figure evokes Raphael’s Roman period, and it was most likely painted sometime between 1513 and 1516. The true beauty of the work, a half-length image of an unknown sitter, radiates from its mysterious aura. The figure is clothed in a puffed white camicia with a thick marten’s fur thrown over his (or her) left shoulder. The youth acquires a nonchalant pose, resting his right forearm on an Anatolian rug laid on a table. A black beret is caught slightly slipping down the hair. The sitter evokes a certain casualness, or sprezzatura, which – in the words of Castiglione Baldassari – “conceals all artistry and makes whatever one says or does seem uncontrived and effortless.”

The identity of the sitter has not been confirmed to this date. Scholars have described the youth as a young man; a woman; Federico Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua; Francesco Maria della Rovere, Duke of Urbino; or Evangelista Tarasconi of Parma, also known as Parmigianino, the supposed lover of Pope Leo X. Others believe that the painting is a self-portrait. Princess Izabela Czartoryska, the founder of the Czartoryski Museum, described the painting in a 1828 catalogue of the collection as “a portrait of Raphael, painted by his own hand.” This was a prevalent theory among her contemporaries. The true identity of the youth remains a mystery, largely due to vast gaps in the provenance prior to entering the Czartoryski collection at the turn of the nineteenth century.

Part 1: Mapping the Journey from Italy to Poland

Gothic House, Puławy, Poland, circa 1850

The earliest confirmed provenance traces the painting to the collection of the Czartoryski Family, one of the most prominent princely houses of Poland. It is the mentioned in the 1828 Czartoryski CATALOGUE that locates the painting in an upstairs office of a Gothic house, a small neo-gothic building on the Czartoryski’s property in Puławy. In the catalogue entry, Izabela Czartoryska specified that the painting was purchased by Princes Adam Jerzy and Konstanty Adam Czartoryski from the Giustiniani Family of Venice. However, there are no surviving official documents that record the transaction.

A few years ago, I travelled to Kraków where I met Janusz Wałek, a renowned art historian and former curator of Italian paintings at the Czartoryski Museum. He introduced me to Pieter Jan de Vlamynck’s engraving of the Portrait of a Youth housed in the Czartoryski archives, which sheds more light on the potential provenance of the painting. Below the engraved image of youth, there is an inscription that identifies the Duke of Mantua as a previous owner and M. Reghellini de Schio as the then-current owner of the original painting. The engraving most likely refers to Marcello (Martialis) Reghellini de Schio, Italian-born historian of antiquities that lived in Brussels. The inscription is supported by a record of Raphael’s self-portrait in an 1826 catalogue listing Reghellini’s art collection that belonged to the Duke of Mantua prior to 1630.

Famed art historian Giorgio Vasari stated that Giulio Romano, one of Raphael’s closest pupils, inherited Raphael’s works after his death in 1520. Some scholars hypothesize that Romano brought the painting to Mantua in 1524. If Portrait of a Youth was indeed in Raphael’s possession until his death, it would be possible that Romano brought it with him when he began working at the court of Gonzaga. In this case, the painting would have avoided the Sack of Rome of 1527.

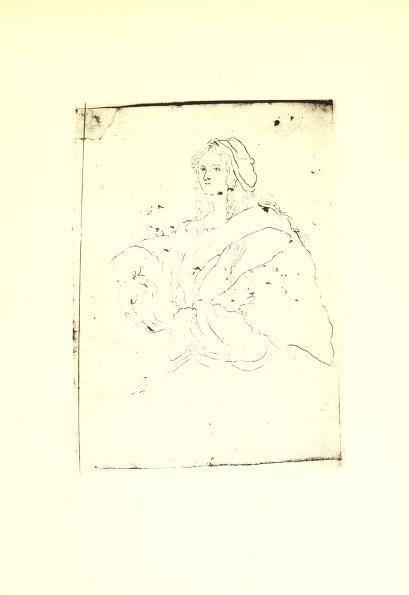

Between 1621 and 1627, Flemish painter Anthony van Dyck memorialized his journey through Italy in a SKETCHBOOK, in which he included a quick sketch of Raphael’s Portrait of a Youth, tracing the soft folds of the sitter’s clothing. Van Dyck began his travels in Genoa in November of 1621. He then briefly visited Rome in February 1622, and then went on to Venice, stopping in Florence and Bologna on the way. He then traveled to Mantua and reached Turin in January of 1623. Soon after, he returned to Rome, where he stayed for a few months. He then went back to Genoa and remained there until 1627, having visited Palermo in the summer of 1624. Unfortunately, it is not known where van Dyck saw Raphael’s painting. The sketch was drawn on a folio next to a portrait of Sofonisba Anguissola, which is the only drawing in the sketchbook that is inscribed (July 12, 1624, Palermo). Although the sketchbook is not sorted in a precise chronological order, we are confident that upon seeing the charming work of the Renaissance master, van Dyck could not help but retrace the enigmatic figure on the other side of the frame. The Flemish master’s drawing offers evidence that situates the painting in Italy in the seventeenth century.

The connection between the painting and the city of Mantua is highly possible considering van Dyck’s sketchbook. However, the de Vlamynck engraving in the Czartoryski Archive most likely depicts a copy of Portrait of a Youth, one that Reghellini aspired to sell to William I, the King of the Netherlands. Sources indicate that Reghellini’s painting was of subpar quality so it was not considered an original work by Raphael. Moreover, the dating of the Reghellini catalogue conflicts with the supposed date of the acquisition of the painting by the Czartoryski Family. (This deviation in the story helps us understand an important lesson in provenance research– always be cautious. For centuries, Raphael’s name has been engraved in the art historical canon and therefore it is not unusual to come across numerous copies, and even forgeries, of his work.)

Nonetheless, a handwritten note below the engraving offers more insights into the history of the Czartoryski painting. The writing dates the purchase of the original painting by Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski to 1808 in Venice. The author of the handwritten note is unknown and the date is also problematic as it is highly probable that Prince Adam Jerzy purchased the painting during his travels in Italy sometime between 1798 and 1801, as he was the only family member to travel to the country at the turn of the nineteenth century.

After the third partition of Poland in 1795, Princes Adam Jerzy and Konstanty Adam were sent to the Russian Court of Tsar Paul I. Prince Konstanty Adam returned to Poland shortly after, but Prince Adam Jerzy remained in Saint Petersburg and began a political career. In 1798, Tsar Paul I sent Prince Adam Jerzy to Italy as an ambassador to a dispossessed King of Sardinia. In reality, Prince Adam Jerzy was sent into exile because of an alleged affair with the wife of the Tsar’s son. Having to part ways from his lover, Prince Adam Jerzy aimed to heal his hollow heart through admiring the Italian culture.

Prince Adam Jerzy first arrived in northern Italy, visiting only the principal buildings of Verona, Venice, and Mantua due to a strict schedule. He then traveled to Florence in the winter of 1798/1799. There, Prince Adam Jerzy visited art collections and studied the Italian language. He also visited Pisa and then moved to Rome, where he embarked on an ambitious project of recording a street map of ancient Rome (this was never completed). After Rome, Prince Adam Jerzy traveled to Naples and Florence again. He briefly visited his mother, Izabela Czartoryska in Puławy in 1801, before returning to Saint Petersburg. Prince Adam Jerzy kept a journal, indicating that he had very little time, if any at all, to acquire the painting in Venice. It is more likely that Prince Adam Jerzy purchased the painting through an intermediary acting on behalf of Venice’s Giustiniani Family, with the work most likely located in an Italian city other than Venice.

During his travels, Prince Adam Jerzy regularly corresponded with his mother, Princess Izabela Czartoryska. Their letters reveal a maternal love with which Izabela embraced Adam from afar. In return, Prince Adam Jerzy sought to find the most treasured gifts for his mother to fill the walls of her new museum. She expressed ambivalence about acquiring new works and instead asked for antiquities. Princess Izabela liked souvenirs that focused on conveying stories rather than mere objects destined solely for aesthetic pleasure. Although there are multiple sources from the Czartoryski Archives that pinpoint different acquisition times for Portrait of a Youth (as recounted above), we do not have any surviving official documentation that records the exact transaction. Based on the available information, we can deduce that the first time Raphael’s painting left its home country was through the acquisition by the Czartoryski Family.

Part 2: Following the Masterpiece’s Footsteps During Wartime

After residing in the Gothic House in Puławy, Raphael’s Portrait of a Youth traveled around Europe, escaping wars during the nineteenth century. During the November Uprising in 1830, the painting was walled-up in a basement of the Czartoryski’s palace in Sieniawa, in southeast Poland. After a few years underground, the portrait was moved to Hotêl Lambert in Paris along with Rembrandt and da Vinci’s paintings. In 1848, Portrait of a Youth was sent by Prince Adam to a London-based antiquarian in the hope of selling it. The painting remained there until 1851, when it was sent back to Paris. The painting returned to Kraków shortly after the inauguration of the Czartoryski Museum in the 1880s. In 1893, it was exhibited in the museum, on a wall left of the entrance, hanging above a neo-Renaissance chest decorated with Florentine cassoni on the sides. After the start of World War I, the painting was loaned to Gemäldegalerie in Dresden in 1915. It remained on public display there until July 1920 when it was returned again to Kraków.

In anticipation of the next war, General Marian Kukiel, the director of the Czartoryski Museum in Kraków, began preparing plans to secure the art collection in April 1939. On August 24, the portrait was transported by truck to the Czartoryski’s palace in Sieniawa. Portrait of a Youth was kept in a wooden chest signed LRR (meaning “Leonardo, Raphael, Rembrandt”). In Sieniawa, the LRR and other chests were hidden behind a brick wall in the basement, in the same location as in the 1830s. On September 15, German soldiers began occupying the Sieniawa palace. On September 18, 1939, they raided the basements and demolished the walls, discovering the Czartoryski’s treasures and breaking into the LLR trunk. The soldiers took precious metal and jewelry, leaving the paintings behind. After the incident, German authorities refused to acknowledge the theft and placed the blame on local delivery boys carrying eggs and butter to the palace kitchen.

On September 20, 1939 the LRR chest was sealed behind the same basement wall. Two days later, the owner of the collection, Prince Augustyn Czartoryski, moved it to his residence, the Pełkinie Palace. It was roughly ten miles south of Sieniawa. Eventually, the head of the regional Gestapo learned about the collection and demanded it for security reasons. The Gestapo also imprisoned Prince Augustyn who eventually escaped from the Nazi regime with the help of the Spanish Royal Family. On October 23, Witold Czartoryski became in charge of the collection after Augustyn fled and was forced to sign a document agreeing for Gestapo to secure the Collection. From that moment on, the Nazi government became in charge of the Czartoryski Collection.

Shortly after, the collection was moved to the Jagiellonian Library in Kraków. A team of art experts examined the artworks before shipping them to Kaiser-Friedrich Museum in Berlin, where Adolf Hitler and Hermann Göring saw the LRR for the first time. Two months after, Hans Posse suggested to Adolf Hitler that the LRR should be moved to the planned Adolf Hitler Museum in Linz. In December 1939, the LRR was split for the first time. Da Vinci’s Lady with Ermine was moved to Kraków to accompany Hans Frank, whereas both Rembrandt’s Landscape with a Good Samaritan and Raphael’s Portrait of a Youth remained in Berlin. During the Nüremberg Trails, Kajetan Mühlmann Austrian art historian and SS officer Kajetan Mühlmann provided an inventory of a safe in Deutsche Bank in Berlin located on Unter den Linden Strasse, which included Portrait of a Youth. Raphael’s work remained as a deposit in Deutsche Bank until July 1943 when Mühlmann personally handed the painting to Wilhelm Ernst Palézieux for the purposes of decorating Frank’s offices in Wawel Castle in Kraków. By mid-1943, the Soviet forces were moving closer to the Nazi occupied territories, and Frank began to prepare evacuation. During the first days of August 1944, the painting was transported by a train to a palace of Manfred von Richthofen in Sichów, Lower Silesia. This is the moment when the trail goes cold.

German authorities prided themselves in organization and were excellent record keepers. However, it is also easy to make documents vanish during times of chaos. A significant amount of information about Raphael’s Portrait of a Youth from the year 1944 onward heavily relies on oral testimony. In 1964, Dr. Eduard Kneiser, a conservator working for Frank, testified that he saw Portrait of a Youth in Richthofen Palace and that it was later seen in the residence of the von Wietersheim-Kramst Family in Muhrau (present-day Morawa). On January 25, 1945, Frank relocated to Neuhaus, Bavaria. The next documented inventory of the Neuhaus location was drafted by the Monuments, Fine Art, and Archives team in May of 1945. This inventory listed the other two paintings comprising the LRR, but it didn’t include our Raphael. It is hypothesized that before Frank relocated, he gave the painting to local authorities for safekeeping in Muhrau. Perhaps this was due to the work’s inconvenient size (28 x 23 inches; 70 x 59 cm). What we know is that the painting most likely disappeared somewhere in the Polish region of Lower Silesia. The fate of Raphael’s Portrait of a Youth remains unknown.

Since the end of the Second World War, many have tried but failed to recover the lost painting, including Stefan Zamoyski, the husband of Elżbieta Czartoryska; the director of the National Museum in Warsaw Dr. Stanisław Lorent; the FBI; as well as Polish, English, and German authorities. Over the years, information gets lost. Hans Frank was tried and executed in Nuremberg in 1946. Kajetan Mühlmann passed away from cancer in 1958. Wilhelm Ernst Palézieux died in a car crash in 1953, only weeks before an appointed meeting with Zamoyski concerning the investigations. Raphael’s portrait remains missing to this day.

During World War II, Poland suffered from extensive plunder and confiscation of heritage; ever since, the government and the public have made extensive efforts to recover and repatriate their cultural property. Raphael’s Portrait of a Youth has become strongly embedded within official heritage narratives in Poland and the lost artwork is at the forefront of the national campaign for art restitution. After the fall of communism in Poland, Prince Adam Karol Czartoryski as the rightful heir reclaimed the rights to a portion of the Czartoryski Collection. In 1991, he established the Princes Czartoryski Foundation, which took care of the recovered artworks, including Rembrandt’s Landscape with a Good Samaritan and da Vinci’s Lady with Ermine. In 2016, the Polish government acquired the Czartoryski Collection, including property rights to the missing painting. Today, the painting lives on in a DIGITAL DATABASE of wartime losses in Poland. It is important to be vocal about lost cultural heritage and not stop looking for it. As Raphael’s Portrait of a Youth lives through its many reproductions, may its ghost haunt bad faith purchasers or others knowingly concealing its hidden location.