by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 31, 2023 |

Good news, thrill-seekers! Here at Amineddoleh & Assoc., not only do we provide exquisite legal services for our clients, we also know where to find a good, real-life scare. Our secret? Follow the haunted art!

Read on for our recap of our firm’s top haunted art-themed blog posts. Then, book a ticket to see the haunted art in-person. No tricks here, each destination is a true, Halloween treat.

Witch Way to the Party?

In this recent blog post, our firm traveled to Asheville, NC to get a glimpse at America’s Largest Home – and one of the most haunted. Click the link for all the details on this spooky mansion, including its most famous ghost-in-residence. Not only that, this historic home has a strange room known as the Halloween Room for visitors to experience, plus its own secret connection to protecting American art from Nazi air-raids in WWII. As if that weren’t enough to encourage a click, this post also has dazzling photos of Asheville’s gorgeous fall foliage.

Biltmore House in Autumn. Image via R.L. Terry at Wikimedia Commons.

The Ghoulishly Gory Frescos in Rome’s Santo Stefano Rotondo

Ever see art so gory it incites a physical response? Click here for more info on this real-life syndrome, known as Stendhal Syndrome, in which grotesque art and cultural heritage causes viewers to have palpitations of the heart. For those wanting to experience the syndrome in real-life, look no further than Santo Stefano Rotondo in Rome. While most tourists on a Roman holiday select beautiful frescos at the Vatican, those who venture to Santo Stefano will see a different sort of religious art. Go for the scenes of torture, stay for the bloody depictions of senseless violence. Plan to go before lunch, or else risk spilling the contents of your own stomach at the foot of these cultural works.

Gory frescoes covering the walls of the church. Image courtesy of Leila Amineddoleh, used with permission.

Cursed Art, from Statues to Paintings

Anglophiles, unite! The National Gallery in London is home to one of the most famous paintings in the world. However, this work is not famous for its artistic qualities (though they are divine). Rather, The Rokeby Venus is better-known for its ability to cause viewers to lose their minds. Click here to read all about this painting’s astonishing – and potentially cursed – provenance. The strange stories behind The Rokeby Venus illustrate how all aspects of a work’s life – including whether or not it is cursed – create its provenance. No matter what your opinion is of The Rokeby Venus’ alleged curse, the documented history of strange occurrences attributed to its ownership has become an important part of the work’s provenance.

The slashed Rokeby Venus. Image via artinsociety.com.

Haunted Happenings: The Law of Ghosts and Home Sales

If the average Airbnb isn’t scary enough this season, consider visiting a house that’s actually haunted. More and more people are reporting ghosts in domestic settings – and not always friendly ones. Trouble ensues when the place the ghost calls home is up for sale. Lawyers may be faced with the question: is a ghostly presence a condition that must be disclosed prior to sale? Would a reasonable family purchase a house that comes with a frightening ghost? Read more here to discover the actual laws that govern when a family’s new home comes with an unexpected side of ghost.

Famous ghost photograph of the Brown Lady of Raynham Hall, originally taken for Country Life (first published in December 1936).

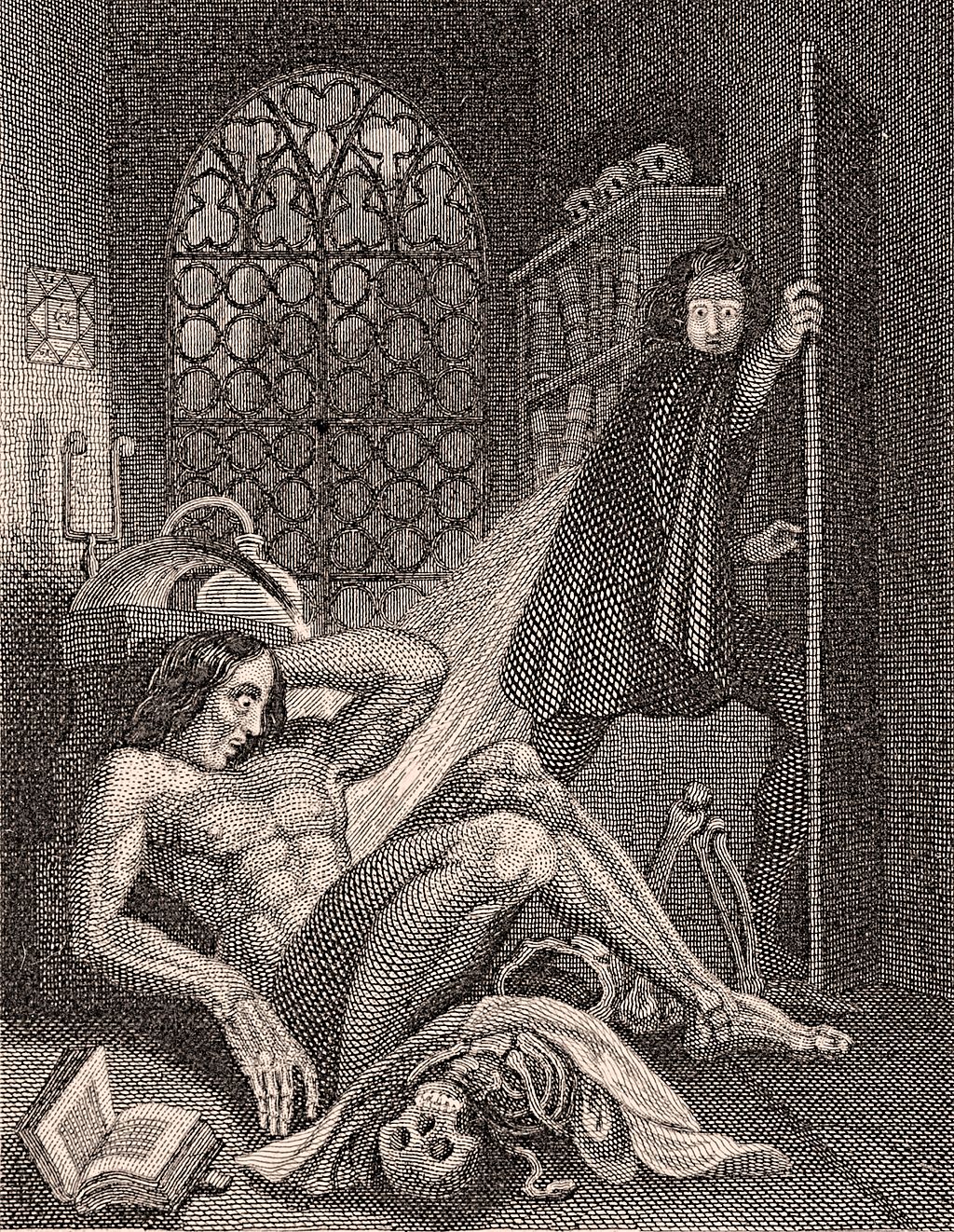

Horrifying Provenance of Monster Manuscripts

This post provides two monstrous holiday destinations in one spooky swoop: ties to Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein can be found in both New York City and Oxford, England. Online versions of Shelley’s copious notes and edits for the story can be found on The Shelley-Godwin Archive’s website through the New York Public Library. To pay a visit to the originals, travel to Oxford, where the original transcript are held as part of the Abinger Collection in the Bodleian Library. If that weren’t reason enough to visit Oxford this time of year, stop by Christ Church College for the Harry Potter-esque tour of the storied grounds. Glimpse the inspiration for the wizarding world’s tall towers and cavernous halls on the college campus. Who knows – wizards also might be walking the grounds, masked in their muggle clothes.

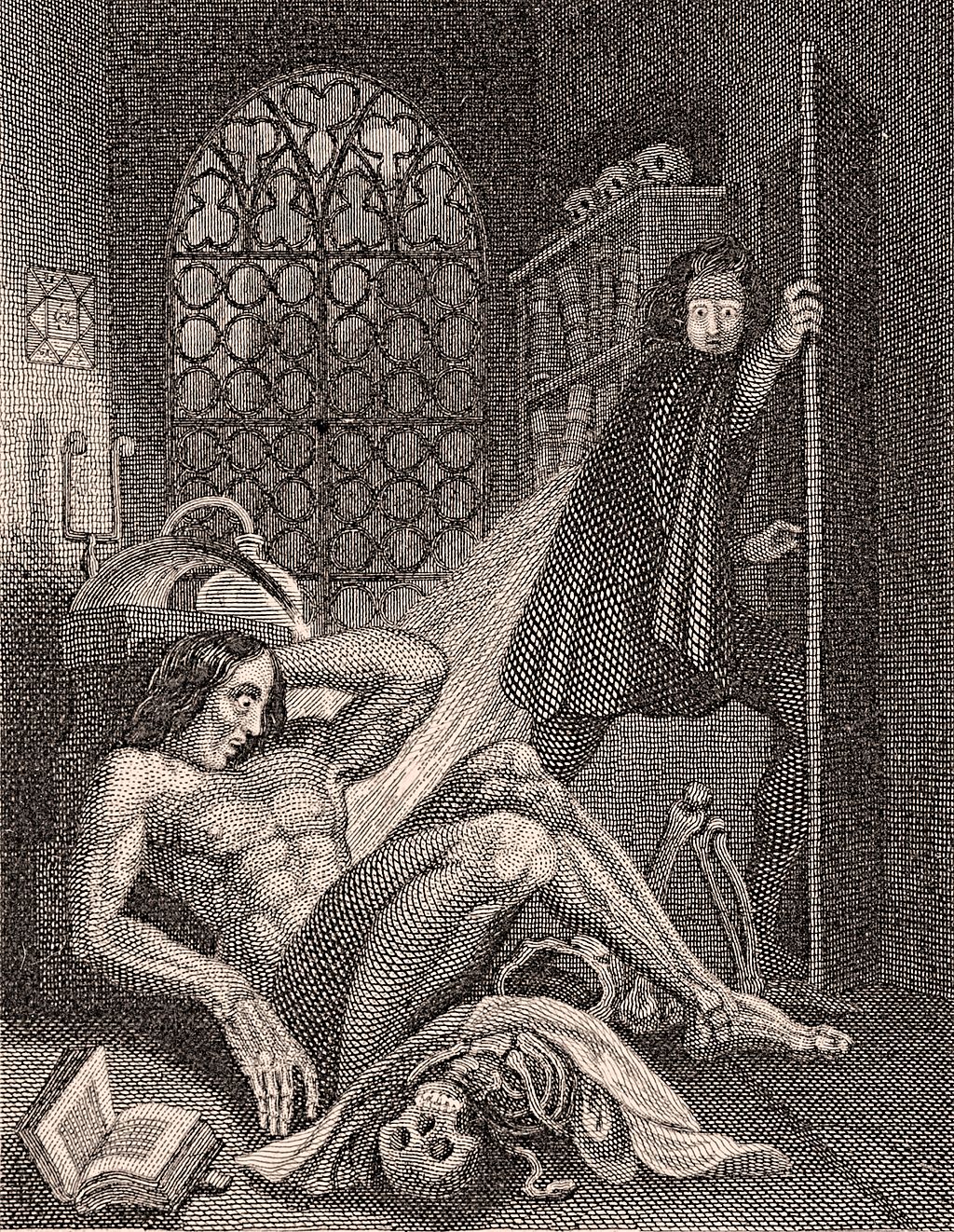

Illustration from the frontispiece of the 1831 revised edition of Frankenstein, published by Colburn and Bentley, London 1831.

The Cat’s Meow: Feline Art Lovers

Word on the street is that the husband of our firm’s founder is dressing as a cat for the second consecutive year this Halloween. While we can neither confirm nor deny the Halloween costumes of our firm’s families (or whether or not, in fact, the members of those families were given the freedom to select their own costumes, or if they were selected for them by their young daughters), click here for a post inspired by our culture’s love for cats in art. Thinking of dressing as a cat this year? As our founder’s husband may say, ‘tis the season!

On behalf of Amineddoleh & Associates, we wish you a safe and Happy Halloween this year!

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Apr 22, 2023 |

Anyone who has been a student knows that the fastest way to capture someone’s attention in a noisy cafeteria is to start a food fight. Last summer and fall, something similar happened in the art world, as museums became the backdrop for messy protests. Now, after a short repose, the culprits are at it again. This time, the action is taking place in Italy, with the most recent attack on art having occurred on March 17th in Florence.

Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, Italy. Image via JoJan through Wikimedia Commons.

Wait, What’s Going On?

The targets are priceless pieces of art and cultural heritage. The culprits are climate activists from several distinct groups with the same singular message: pay attention to climate change. The settings are (formerly) peaceful, as in this last attack in Florence.

In Florence, climate activists disrupted an ordinary day by spraying paint over the outer walls of Palazzo Vecchio. That attack on cultural heritage comes on the heels of the destructive actions taken against artwork in museums around the globe. Soup, cake, ink, and even super glue have been haphazardly applied to the most famous works of art in museums’ prized collections within the past year.

Many of these attacks occurred last summer and fall. Then, around the New Year, there was a brief repose. Art world insiders were optimistic that this trend would stop entirely. Time Magazine reported earlier this year that one major group, Extinction Rebellion, had announced a shift away from flashy civil resistance tactics to gain support for their cause. Instead, the group stated their plan to devote energy to large-scale protests that do not break the law. If other climate change groups followed suit, this would mean a dramatic departure from the ink-splattering and soup-slinging tactics directed at fragile pieces of art and cultural heritage.

Unfortunately, a change in tactics does not seem to be the cards. Not only was the fear that these attacks would continue realized by the recent protest in Italy, a quick check-in with the notorious Just Stop Oil climate activist group – of art attack fame – confirmed their general intention to carry on with the practices of last year. The group, in response to Extinction Rebellion’s statement, promised to “escalate” their actions of civil resistance and public disruption. The group even threatened to begin slashing famous paintings – yikes!

First Rule of Fight Climate-Change Club: Talk as Much as You Can About Fight Climate-Change Club

Van Gogh, Sunflowers, 1888. On view at The National Gallery, London.

The purpose of these art attacks is to get people talking. One recent attack last November was from a group called Last Generation Austria, in protest of Austria’s reliance on fossil fuels. Two activists threw black liquid (presumably representing oil) at the delicate 1915 painting Death and Life (1915) by Gustav Klimt. One activist was promptly removed from the scene by security. The second succeeded in gluing his hand to the glass panel encasing Klimt’s valuable painting. This gluing action was a serious risk both to the safety of the dizzyingly priceless piece of cultural heritage behind the glass, and to the climate activist’s personal hand health. It seems the activist cared very much for climate change, but very little for his hand.

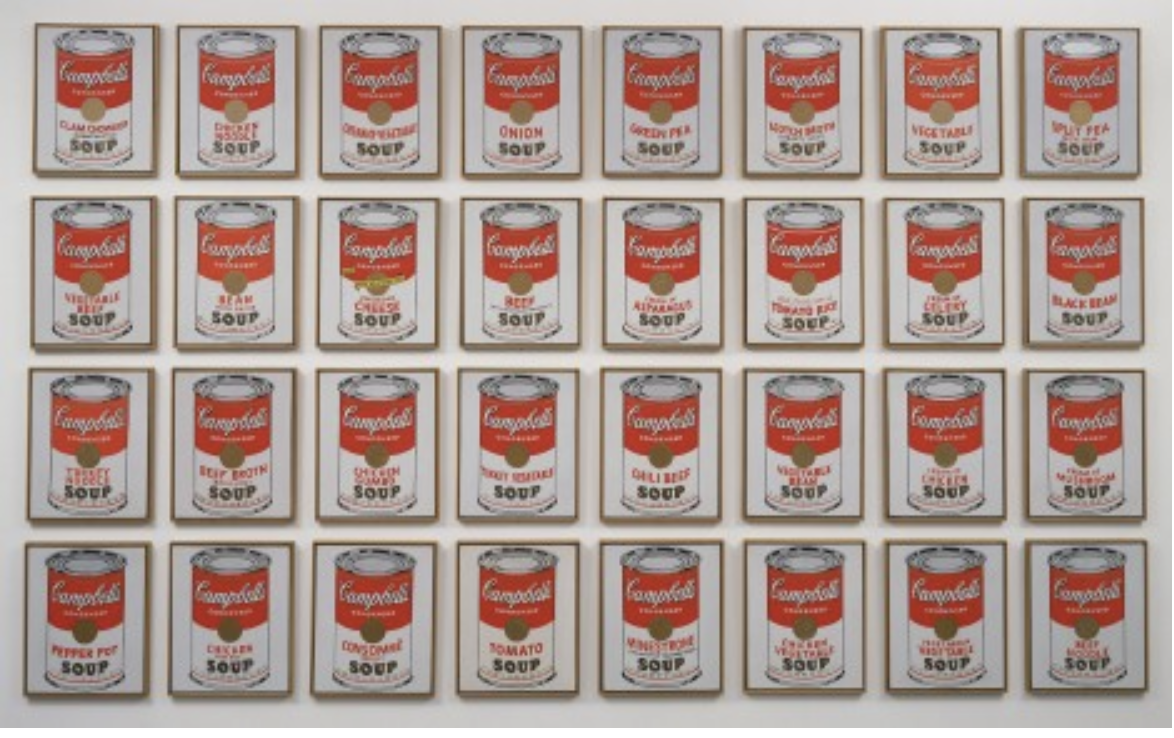

The above attack was likely inspired by the group that finds itself the major instigator of this global operation. Just Stop Oil (the O.G. art attack tribe of climate protestors) has been at this game since earlier last summer. The most publicized attack by Just Stop Oil featured a pair of activists throwing tomato soup at Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers. During the attack, two 21-year old activists leaped over the velvet ropes stationed in front of Van Gogh’s painting, removed their jackets to reveal matching “Just Stop Oil” t-shirts, and slapped soup onto the painting. Not only is this display of wanton disregard shocking, but it boggles the mind that the target of the soup-based attack was not a Warhol work!

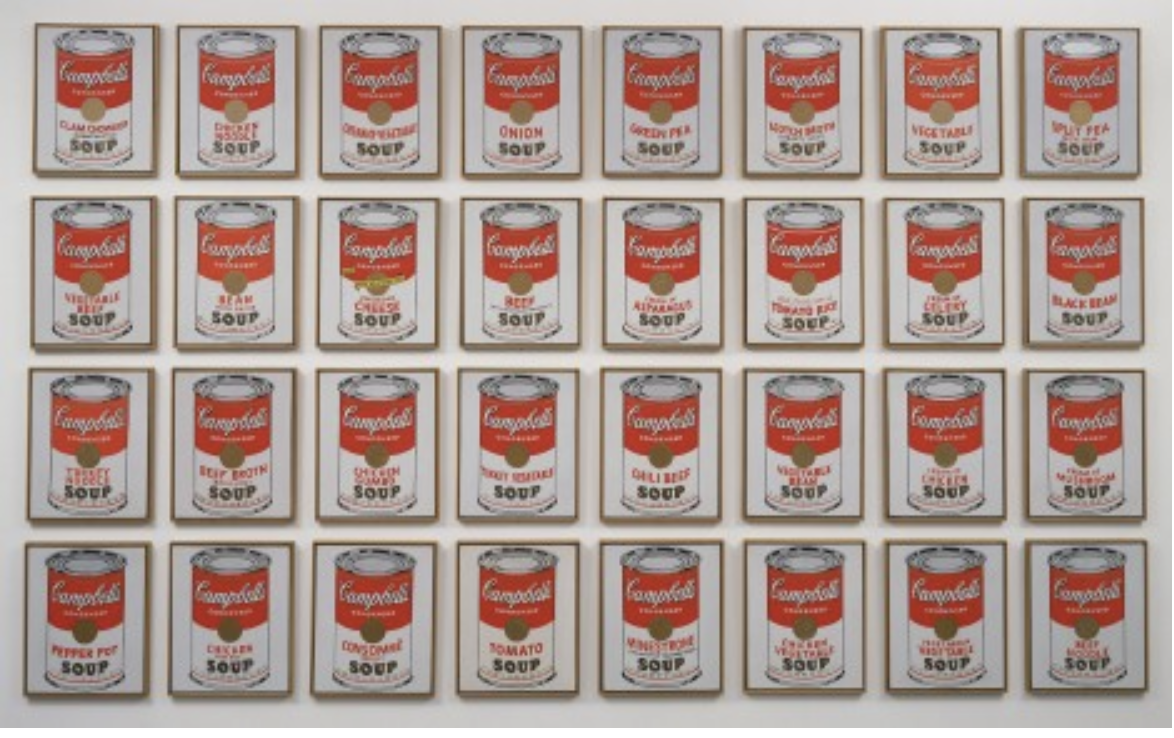

The attack seems to be connected to another recent event of art vandalism that took place that same month in the National Gallery of Australia. That incident involved members of a different group, Stop Fossil Fuels, scribbling ink on Andy Warhol’s screen prints of soup cans. The similarities cannot be ignored, as they follow a similar attention-mongering logic. However, why Just Stop Oil applied soup to varnish, while Stop Fossil Fuels applied varnish to soup, is a total mystery.

The above examples are merely a sampling of the demonstrative protests that have occurred in major museums since the beginning of the summer. They all follow a similar pattern: either a defacing with food or liquid, or protestors gluing themselves to a frame or glass. The latter is an imitation of the form of “locking” protest, in which activists will chain themselves to a stationary object to make it more difficult to be removed by authorities.

Fortunately, it seems that the works involved were unharmed, since they are protected by glass and other protective casings applied by art conservators. In the case of Just Stop Oil and Sunflowers, it was publicly known that the tomato soup would not damage the painting (according to Emma Brown, the founder of Just Stop Oil). Brown asserts that her group’s motivation has never been to destroy art. Rather, it is to engage in a conversation about why damaged artwork incites rage, while news reports of climate change do not.

Andy Warhol, Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962). Image via AP News.

This is not an illogical question, when framed in the proper context. However, when news reports of food being thrown in national galleries are splayed across individual computer screens, the intentions of Just Stop Oil’s efforts are lost in the absurdity of the situation. Food throwing, it seems, is better left in the era of summer camp hijinks.

It seems that the message may have been lost on the public, and that the method of protest may be too radical. In this way, they may be ostracizing potential friends of the cause by turning them off with their flamboyant and messy displays of passion. This would result in the activists seeming to be more like vandals to be avoided, rather than potential friends to be admired.

In fact, these stunts create animosity with museums and the public. By using art to stage protests, museums are now heightening security, leading to a less personal experience at art institutions. Increased security measures and the temporary removal and cleaning of artworks is an added expense for our public institutions. After significant drops in revenue during COVID pandemic, the last thing museums need is to waste funds cleaning up after these messy stunts.

Iconoclasm and Art Vandalism

Just Stop Oil’s flashy protests are not the first instances of art vandalism, nor will they be the last, as art vandalism has a long history of activists using destruction to send a political message. Dr. Stacy Boldrick, author of Iconoclasm and the Museum, explores the history of iconoclasm, which she defines as “image-breaking.” Public perception of iconoclasm influences how the broken image enters a culture’s consciousness, which can result in an almost secondary, separate work of art that begins a life of its own. Even if the piece is restored to its original glory, photos of the work in its defaced form become famous symbols of a particular political movement.

An example of this is none other than the famous Rokeby Venus, and its slashing by suffragette Mary Richardson in protest of the oppression of women. Readers of the blog will recall our firm’s piece on work (for a refresher, click here), and its haunted provenance. The history of the work influenced newspapers of the time to claim Richardson was acting from psychosis induced by Venus’s beauty. Boldrick, on the other hand, makes an argument for Richardson as a legitimate defender of the rights of women, though one who took her message to the extreme. Setting Richardson’s mental state aside, the images of the slashed Rokeby Venus are nearly as impactful as the restored version. The photos of the slashed painting draw the eye toward the ostentatiousness of Venus’s body, framing the voluptuous woman in a context of forced femininity.

The slashed Rokeby Venus. Image via artinsociety.com

Another example of a defaced work sparking its own conversation occurred following artist Tony Shafrazi’s 1974 defacing of Picasso’s Guernica. Shafrazi strode up to Guernica and spray painted “KILL LIES ALL” across the piece, in protest of America’s involvement in the Vietnam War. Fortunately, the painting itself was protected by a heavy coat of varnish. Museum curators were able to quickly clean off the spray paint. Even so, the photos of the defaced work, prior to the cleaning, became political messages. Moreover, Shafrazi himself went on to use the fame garnered by his demonstration to fuel his own artistic career. He is currently still doing well as a successful gallery owner and art dealer in New York.

Shafrazi proves that images of defaced art can send a cultural message by spreading the agenda of the activist who vandalized the work. However, sending a message does not always result in actual change on an individual level. If activists truly desire to change public behavior, there are more effective ways to evoke such action – ways that do not involve defacing fragile, famous works of art. Additionally, museums themselves can take action to promote sustainable, collaborative conversations with activist groups, all while keeping the art safe (and away from tomato soup).

Special Exhibitions

The North Carolina Museum of Art put on an exhibition this past summer that would have appealed to Just Stop Oil’s team of activists, because the show featured artists whose work brings attention to the dangers of climate change. The show, Fault Lines: Art and the Environment, featured artists such as Willie Cole, who did a site-specific installation of a chandelier made entirely out of single-use plastic water bottles. Another artist, Richard Mosse, exhibited works that used infrared technology applied to aerial photographs of geological locations to raise awareness of issues such as deforestation. Featured works of Mosse included: Aluminum Refinery, Paraguay; Burnt Pantanal III; Juvencio’s Mine, Paraguay; and Subterranean Fire, Pantanal.

Richard Mosse, Girl From the North Country, 2015. Image via artsy.net.

Also shown in the exhibit were works created by sisters Margaret Wertheim and Christine Wertheim, whose whimsical crocheted coral reef draws attention to the devastating impact of climate change and plastic trash on the lives of coal reefs. The sisters also did an installation called The Midden, which was constructed of the trash the duo collected walking on the beach over a period of four years.

This writer, a visitor of the exhibit, was particularly influenced by the Wertheim’s trash collecting piece and by the plastic bottle chandelier by Cole. As the writer herself was sipping from a single-use plastic bottle, she was made aware of her personal impact on climate change as a visitor of the exhibit. The writer immediately vowed to use reusable water bottles from that moment on. She joined others on the way out of the exhibit in pledging to reduce all single-use plastics by dropping a recyclable token into the glass canister provided by the front door.

The purpose of the exhibit was to use video, photography, sculpture, and mixed-media works to offer new perspectives in addressing urgent environmental issues. The exhibit highlighted the consequences of inaction, while providing opportunities for patrons to take their own steps towards sustainable environmental stewardship and restoration. This resulted in a celebration of the creation, rather than the destruction, of art in its fullest capacity to send a message to society. By focusing on creation, patrons were encouraged to be part of a constructive solution to climate change alongside the artist activists who produced the pieces shown in the gallery. When asked how about the public response to the exhibit, Virginia Ambar, Assistant Director of Ticketing and Visitor Experience at NCMA said this: “Many people commented on how important it is to highlight our collective roles in affecting our environment and that the exhibit did that in ways that were both startling and beautiful.”

Museum Joint Statement

One way museums have been guarding themselves against art attacks has been to increase private security methods on museum grounds. These increased security measures have taken the form of additional guards, added cameras, and metal detectors – which all come with their own costs. Increasing security is a pricey endeavor, and not one that most museums have the budget for, particularly coming out of the hardships museums faced during the pandemic lockdowns.

Another option is for major public institutions to continue releasing joint statements concerning these matters. The International Council of Museums (ICOM) released a statement signed by over 90 museum leaders. Included among the high-profile supporters were figures from the Prado, the Guggenheim, the British Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The statement explains the precariousness of the art being targeted, and highlights the vulnerability of delicate works of art, even when they are protected behind glass. While the statement does not address the issues raised by climate change, it does draw a clear line in the sand to draw attention to the riskiness of targeting these fragile and irreplaceable treasures.

Climate protestors march through city centers, causing traffic delays. Image via juststopoil.org

It is a showing of museum solidarity against protests. Its impact is yet to be seen, but there is hope that the statement will have an impact on protestors. The breadth of the ICOM statement, combined with the released statement by the American Association of Museum Directors on the same topic, last year, might speak to the protestors in a way that results in fewer art attacks. Taken together, the statements serve to highlight the damage caused by targeting art and the vulnerability of objects used in protests, without casting judgment on the protestors’ message. Rather, these statements encourage compassion on a global scale. Being good stewards of art and advocates for the environment both involve recognizing ways to nurture our shared humanity.

Conclusion

Collaboration is a better way forward than flashy protests. The lifespan of a shocking protest is only that of the flash-in-the-pan clickbait headline. As such, the political messaging of Just Stop Oil continues to be lost in the noise of the internet. Moreover, the fact of the matter is that throwing food at art to send a message is not sustainable. The shock value wears off eventually. It also wastes food and paint, not to mention the environmental impact of cleaning up the destruction. Remember the Italian climate activists’ recent activity in Florence? Ironically, even their spray painting seems to have caused more environmental harm than good. Nardella, the mayor of Florence, reported that “more than 5,000 liters of water were consumed to clean up Palazzo Vecchio” following the destructive protest.

Art, on the other hand, is constantly reinventing itself in sustainable ways that are fresh and exciting. Because of art’s evolving nature, activists who choose to work with artists and museums in a constructive, rather than a destructive, way, have the potential to sustainably effect real social change.

It’s a framework for elevated discourse. It smells like progress, not tomato soup.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Sep 9, 2022 |

A New York bill signed into law on August 10, 2022 will require museums to provide a notice to viewers if works of art on display have links to the Holocaust. This groundbreaking and restorative legislation accompanies two other Holocaust-related bills signed into law: one aimed at increasing Holocaust literacy through curricula in educational institutions, and the other designed to increase pressure on banks that assess fees related to Holocaust reparations. All three bills work in concert to combat rising reports of antisemitism through these targeted cultural, economic, and educational channels.

Provenance

While other states are considering enacting similar legislation to increase Holocaust literacy in schools, New York stands apart in dictating these trailblazing requirements for museums to publicly acknowledge the devastating conditions under which they may have acquired certain works. The origin of a work of art is known as its provenance, and its applicability extends beyond Holocaust-era stolen works (you can access our blog post on the fight to prove provenance for Mexican antiquities here). Provenance is important not only to establish a chain of title when purchasing a work, but also to determine its cultural, political, and financial value.

Proving provenance is no small task, particularly when items have been stolen. This task is rendered even more difficult when the theft occurred during or shortly after the chaos of war. In the case of works stolen during the Holocaust, both these hurdles were present, with the added complications of global economic upheaval, unimaginable human suffering, an overwhelming refugee crisis, and the genocide of the class of people from whom the works were primarily stolen. The process of proving provenance for works stolen during WWII typically involves the heirs of deceased Jewish family members bringing claims to museums in hopes of establishing legitimate ownership of works held by a museum through whatever documents were salvaged after the war. This can include references in letters and diaries, family photographs, and bills of sale. The museum then has its own systems to determine the legitimacy of such claims. If provenance is not proven after the museum’s internal investigation, the museum is then able to claim that it “legally” retains the artwork.

Of course, this is devastating news to families seeking to reclaim an important piece of family heritage. If a museum denies heirs’ claims, they may proceed to file litigation. One high-profile example is Gustav Klimt’s portrait of Maria Altmann, titled Woman in Gold. Another is the ongoing Cassirer case, involving the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid. However, these cases often take years – if not decades – to resolve, leaving the artwork in legal limbo until a final decision or settlement is made.

Of course, this is devastating news to families seeking to reclaim an important piece of family heritage. If a museum denies heirs’ claims, they may proceed to file litigation. One high-profile example is Gustav Klimt’s portrait of Maria Altmann, titled Woman in Gold. Another is the ongoing Cassirer case, involving the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid. However, these cases often take years – if not decades – to resolve, leaving the artwork in legal limbo until a final decision or settlement is made.

It is important to keep in mind that Gov. Hochul’s new law does not specifically address the need to return works to individual families (restitution). However, it does bring to light the importance of acknowledging a work’s provenance as an important cultural indicator of the suffering of a class of people, even if it does not repair the harm done to individual families. Thus, the heirs or successors-in-interest of a dispossessed owner will need to rely on alternative avenues to recover their property.

Restitution

The effect of the public notice requirement speaks to justice outside the courts that can be accomplished through the voluntary restitution of stolen artwork. When restitution is carried out by leading art institutions as part of a larger “duty to remember,” it aids in cultivating peace and strengthening non-legal measures of restitution. Furthermore, it sets a positive example for other art world participants. While public art institutions have often not returned potentially looted art to the heirs of their original owners when proof of theft is not evident, many have expressed a desire to not retain stolen work. Even so, museums as a whole tend to be reluctant to part with prized pieces, particularly when the works claimed as stolen are the very ones that draw visitors to their galleries.

Case law

Decades of case law in the U.S. indicate the difficulties facing claimants. Recent cases against New York museums resulted in wins for the institutions, yet not due to the merits of each respective case. Rather, the Museum of Modern Art squeaked out wins through a confidential settlement, and defended itself by claiming that the statute of limitations had run. In another case, the Metropolitan Museum of Art made the affirmative defense of laches, under the theory that claimants made an unreasonable delay in bringing suit against the museum for a valuable painting by Picasso.

Decades of case law in the U.S. indicate the difficulties facing claimants. Recent cases against New York museums resulted in wins for the institutions, yet not due to the merits of each respective case. Rather, the Museum of Modern Art squeaked out wins through a confidential settlement, and defended itself by claiming that the statute of limitations had run. In another case, the Metropolitan Museum of Art made the affirmative defense of laches, under the theory that claimants made an unreasonable delay in bringing suit against the museum for a valuable painting by Picasso.

Even the most recent ruling in the Guelph Treasure litigation did not fare well for the claimant heirs. The Guelph Treasure litigation follows claims brought by the heirs to a priceless haul of German ecclesiastical relics, currently on display in the Bode Museum in Berlin. The heirs claim that the relics were sold under duress to the Nazi government in 1935 for less than their market value. The museum’s foundation argues that the sale was voluntary, and, further, was not made under the pressure of Nazi occupation in Germany.

Last month’s ruling by the District Court for the District of Columbia dismissed the case on jurisdictional grounds, stating that the Foreign Sovereign Immunity Act (FSIA) blocked suit of Germany in U.S. court (this confirms the holding by the U.S. Supreme Court that remanded the matter to the district court). The claimants relied on an exception to the FSIA which prohibits expropriations that violate international law, arguing that dispossession in cases of genocide qualified for this rule. However, the court found that the claimants failed to prove that their ancestors were not German nationals at the time of the sale, meaning that only domestic law – not international law – was involved. As such, U.S. courts do not have subject matter jurisdiction over the matter, meaning that U.S. courts are unable to make determinations on German domestic law.

The district court’s decision does not eliminate the possibility of appeal or further pursuit of the Guelph Treasure through alternate measures in Europe. However, claimants often prefer to file disputes in the U.S. because American courts have historically been more lenient for Holocaust-related actions, particularly on statute of limitations grounds. In most European countries, causes of action for property stolen or lost during WWII have already expired. For example, Poland recently passed legislation that reduced the statute of limitations on all restitution cases to 30 years from the theft’s occurrence; this effectively bars all Holocaust restitution claims.

It is important to note that not all hope is lost. Some museums have, on their own initiative, refused to turn a blind eye to the problematic origins of some of their beloved works. The North Carolina Museum of Art, for example, returned a 16th-century painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder to an Austrian family after learning that the work was stolen by Nazi officials in 1940. And the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (MFA) recently returned View of Beverwijk by Salomon van Ruysdael to the descendants of a Jewish art collector and politican, from whom the work was stolen by Nazi forces.

In the case of the return of View of Beverwijk, the museum and the claimant family each had a role in making the restitution possible. First, the MFA received new provenance information regarding the work and updated its museum website. The family’s lawyer then used that new information to provide a missing link to prove their ancestor’s possession.

It was truly a moment of teamwork, and sets an example for other museums seeking to actively become part of the solution in remedying the trauma of the Holocaust. The MFA’s curator for provenance, Victoria Reed, stated (upon the return), “To be able to redress that loss, even in a tiny way, I think, is gratifying. And it certainly is part of what we should be doing as a museum.”

At the same time, voluntary returns of artwork by museums are few and far between, and the battle for individuals seeking to prove provenance remains a lengthy, cumbersome, expensive, and uphill battle. In light of these hurdles, requiring museums to publicly notify guests of the potentially tragic origins of works they have on display is a start. Doing so gives voice to the people who were silenced under the traumatic and systematic genocide of the Holocaust and lost their homes, families, and ties to their history and culture.

New York’s actions, in this sense, are an act of strength in the face of the general reluctance by museums to acknowledge that there are times in which the display of art may perpetuate war crimes. As Maya Angelou put it, “History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived. But if faced with courage, need not be lived again.”

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Sep 1, 2022 |

A visit to the National Archaeological Museum of Taranto (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Taranto, MArTA) reminded me why I love museums so much. It is an inspiring place, a valuable educational resource, and an underappreciated repository for art and heritage.

Taranto, Italy

Greek ruins (Temple of Poseidon)

MArTA is located in Taranto, a city located along the inside of the “heel” of Italy in the region of Puglia. It was founded by Spartans in 706 BC, and it became one of the most important cities in Magna Graecia (the Roman-given name for the coastal areas in the south of Italy — Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania and Sicily — heavily populated by Greek settlers). Two centuries after its founding, it was one of the largest cities in the world with a population of around 300,000 people. Taranto (called Tarentum by the Ancient Romans) was subject to a series of wars, culminating in its fall to Rome in 272 BC. The city fell to Carthaginian general Hannibal during the Second Punic War, but was recaptured (and subsequently plundered) by Rome in 209 BC. The following centuries marked the city’s decline.

Cathedral of San Cataldo

Taranto’s mix of architecture and rich cultural heritage is due, in part, to subsequent changes in leadership between the 6th and 10th centuries AD, during which time it was ruled by diverse groups: Goths, Byzantines, Lombards, and Arabs. Later, during the Napoleonic Wars in the 19th century AD, the city served as a French naval base, but it was ultimately returned to the Kingdom of Two Sicilies for a few decades before it officially became part of the Republic of Italy in 1861.

Due to its strategic location on the inlet of the Gulf of Taranto, the city has great naval importance. Taranto served the Italian navy during both World Wars. As a result, it was heavily bombed by British forces in 1940 (the bombing of Taranto and was even noted to have “set the stage for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor” the following year). The city was also briefly occupied by British forces during WWII.

Evidence of the city’s various iterations is evident throughout its streets with impressive cultural sites, including the Greek Temple of Poseidon, the Spanish Castello Aragonese (built in 1496 for the then-king of Naples, Ferdinand II of Aragon), and the 11th century Cathedral of San Cataldo (Taranto Cathedral), where the remains of the city’s patron saint, Saint Catald, lie (he is believed to have protected the city against the bubonic plague). More recent architectural gems include Palazzo Galeota and Palazzo Brasini.

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Taranto

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Taranto (MArTA)

Like the city where it is located, MArTA is a rich institution full of incredible treasures. Last month, I had the opportunity to visit MArTA in person. Sadly, the museum, and the city itself, tend to fall under the radar of tourists. It is unfortunate that this site escapes attention, because both Taranto and its vaunted museum are incredible.

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4th century BC. As such, MArTA’s collection is impressive, displaying one of the largest collections of artifacts from Magna Grecia. Besides its rich holdings, this museum is unforgettable because of the ways in which it fulfills its cultural and educational purpose. The museum is arranged and curated along an “exhibition trail” so as to present visitors with a timeline of the city’s history. The displays move through time from the city’s prehistoric era to its Greek and Roman past and its medieval and modern history, in addition to integrating objects from outside Taranto that exemplify its location as a center of trade (including an exquisite statue of Thoth, the Egyptian god of scribes and writing). Toward the end of the trail, visitors are also confronted with information about the modern-day looting of artifacts and the work done to protect the city’s cultural heritage (more on that below).

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4th century BC. As such, MArTA’s collection is impressive, displaying one of the largest collections of artifacts from Magna Grecia. Besides its rich holdings, this museum is unforgettable because of the ways in which it fulfills its cultural and educational purpose. The museum is arranged and curated along an “exhibition trail” so as to present visitors with a timeline of the city’s history. The displays move through time from the city’s prehistoric era to its Greek and Roman past and its medieval and modern history, in addition to integrating objects from outside Taranto that exemplify its location as a center of trade (including an exquisite statue of Thoth, the Egyptian god of scribes and writing). Toward the end of the trail, visitors are also confronted with information about the modern-day looting of artifacts and the work done to protect the city’s cultural heritage (more on that below).

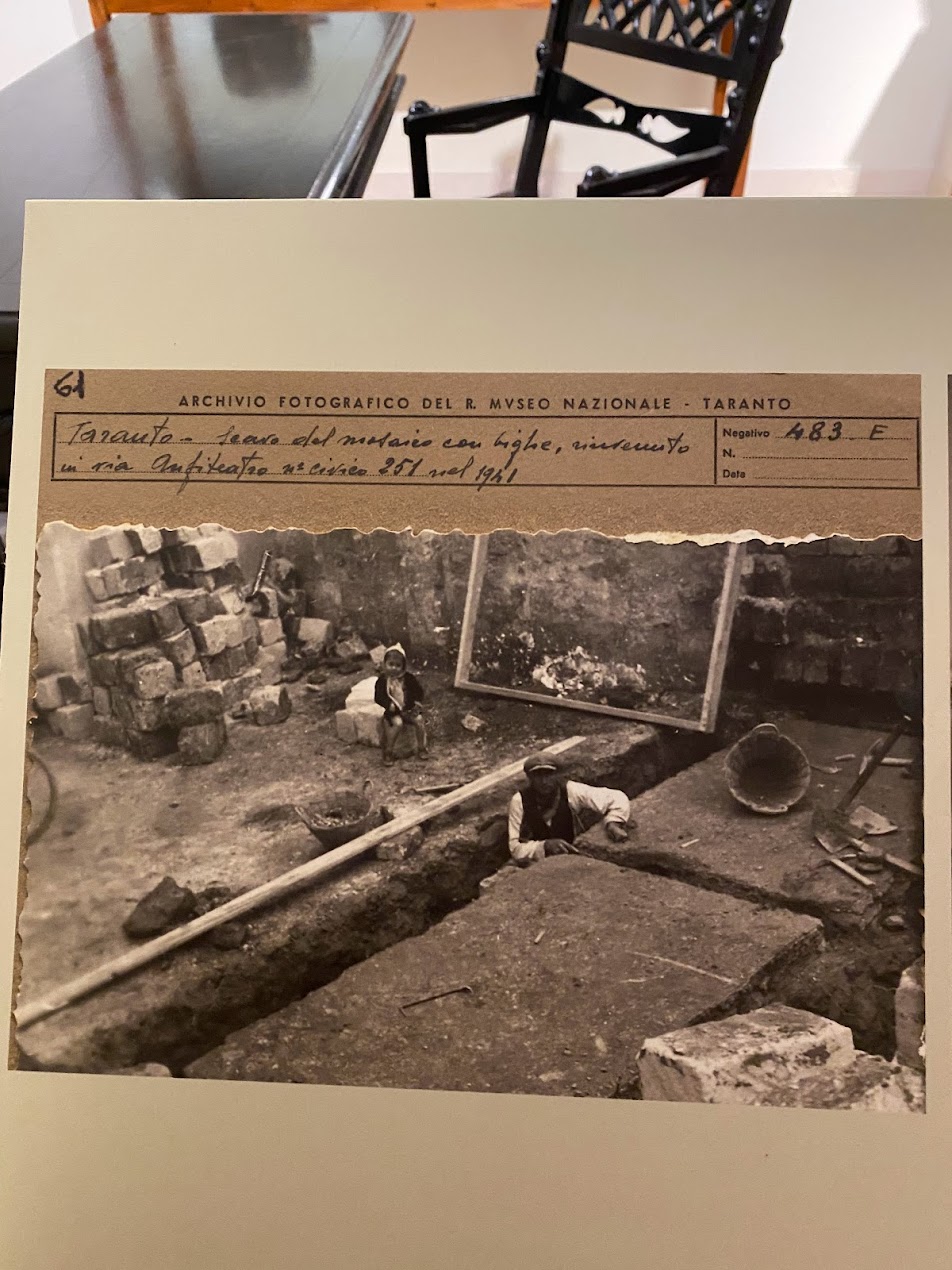

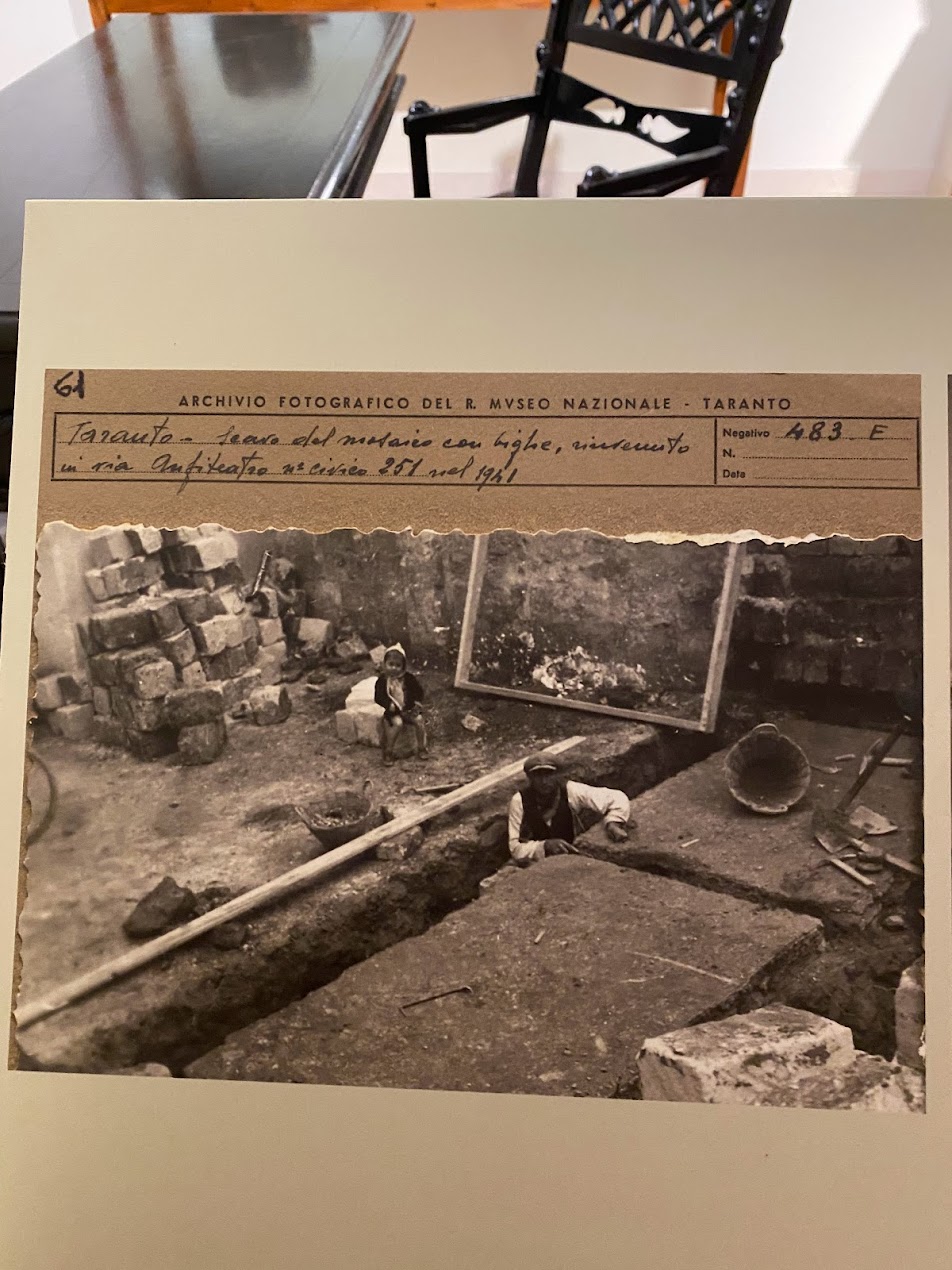

Amongst other treasures in MArTA are beautifully preserved mosaics, ornate golden jewelry, and ancient gold-covered snake skins. Another museum highlight are the informative displays positioning objects in creative contexts. For example, some objects are displayed along with photographic evidence and documentation about their excavation.

Tomb of the Athlete

The museum presents objects in beautiful vitrines. Some of the highlights on the first floor include thematic displays, such as a wall depicting Medusa’s face on antefixes found in Taranto. The curation includes information about the figure of Medusa in mythology and details on how her portrayal evolved over time. Another engaging display involves #italianmuseums4olympics, the Ministry of Culture’s campaign to support Italian sport and culture during the Olympic games. That particular display includes the sarcophagus of an athlete from Taranto, complete with amphorae found in his tomb that include images of athletic competitions, celebrating Italy’s long tradition of participating in the Olympics since antiquity.

An Apulian krater by the Darius painter returned from the Cleveland Museum of Art in 2009

Looting of Objects on Display

As visitors enter the next floor of the museum’s route, they are confronted with a large restituted antiquity. A large Apulian krater by the Darius painter was returned to Italy in 2009 from the Cleveland Museum of Art after it was recovered by the Carabinieri’s TPC (the nation’s famed “Art Crime Squad”). The work was among fourteen artifacts returned from the Ohio museum after a two-year negotiation resulting from the investigation of a looting network run by Giacomo Medici and Gianfranco Becchina, two well-known dealers of looted materials who sold antiquities at auction and through dealers to supply coveted objects to collectors and museums around the world.

Loutrophoros restituted by the J. Paul Getty Villa in Malibu in California

MArTA also acknowledges some of the people responsible for the development of its exquisite collection, including past directors and donors. The displays note that the illicit or unknown sale of antiquities has led to the loss of knowledge about their historical and cultural value (when artifacts are illicitly excavated and divorced from their contexts, valuable information is lost in the process). However, the development of patrimony laws has allowed the Italian government to control more of the archaeological discoveries taking place, and other legislation has also encouraged collectors to donate their property to the museum and Italian State. The display also notes the important work by law enforcement and its success in having works repatriated to Italy, as well as its success in confiscating looted artifacts from private owners and collectors during the 20th and 21st centuries in Italy. Part of this display features works returned from major museums abroad, including the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Getty Museum in Malibu, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Labels and Information

The labels and information offered to visitors at the museum is exceptional, providing valuable information about the historic significance of items on display. Clearly, the museum places great importance on provenance, providing detailed information on where objects were excavated (this information includes exact find spots, with cross streets included for some of the objects), how they entered the museum’s collection, and ways in which the museum has evolved over the decades. Additional information is available to visitors about looting and criminal acts related to the objects, providing useful context.

Copy of the Goddess on Her Throne (the original is in Berlin)

One of the first objects to greet visitors upon their entry is a copy of a goddess on her throne. The original 5th century BC statue is “considered one of the greatest artworks from Magna Graecia.” It was found in 1912 in Taranto, but illegally exported out of Italy. It was then put on the Swiss art market, and finally purchased by the German government. It is currently on display at the Altes Museum in Berlin. Information like this is valuable, because it forces visitors to confront the political, societal, and cultural pressures facing museums, as well as the challenges and realities of the art and antiquities markets. It also provides a practical example of how works can wind up in international museums divorced from their original historical and cultural context.

As the museum’s website states, “The Museum also lends artefacts to other museums to allow global citizens to enjoy. We are aimed at providing first-hand information to all of our visitors so that they understand Europe’s prehistoric period.”

Castello Aragonese

A visit to this museum, and the gorgeous city of Taranto, with its sweeping coastal views, its rich cultural history, and its stunning architectural masterpieces, is essential for anyone visiting Puglia.

Copyrights in all photographs in this post belong to Leila Amineddoleh

ADDITIONAL PHOTOS

Objects from the museum’s early collection

Documentation of excavations

Vitrine (provenance information for each object is provided in a side panel)

Provenance on view

Beautiful entryways on each floor

Context with a photograph

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | May 31, 2022 |

Each May, the art world buzzes as art fairs hit New York City and the major auction houses host blockbuster international sales. After scaling back in 2020 and 2021 due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the art scene returned with gusto this spring. Even the Financial Times noted that New York’s 2022 auction season wrapped up “strongly,” after a series of record-breaking successes.

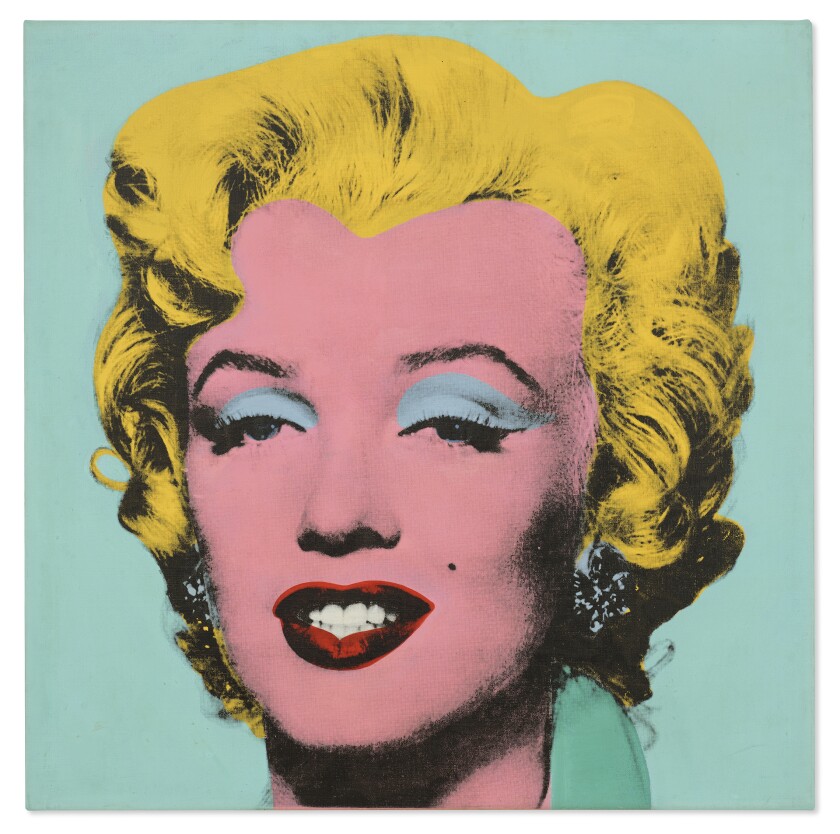

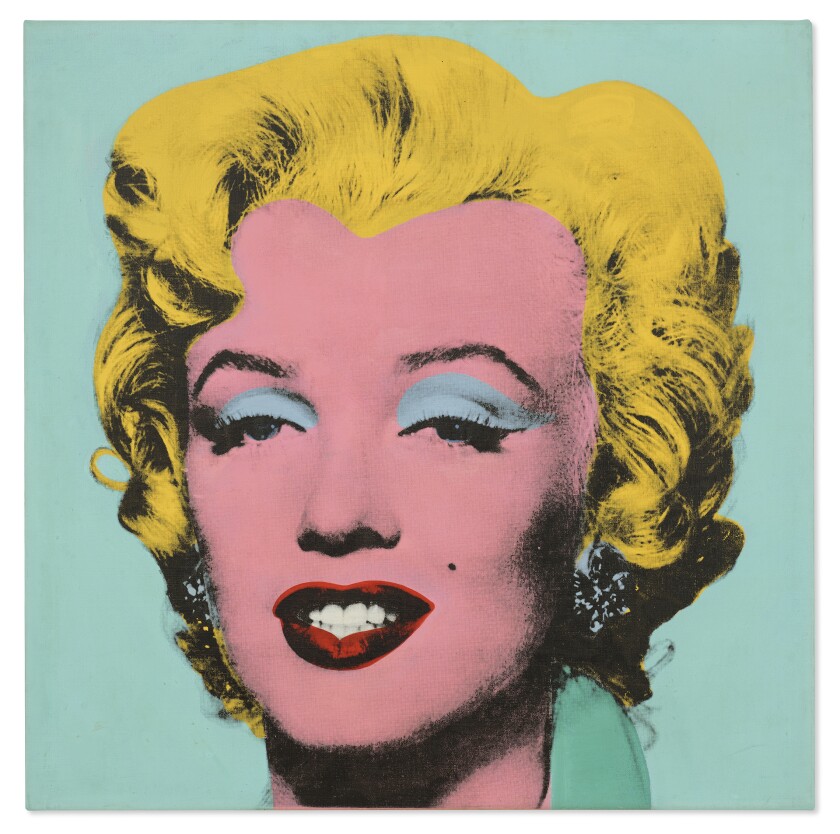

Shot Sage Blue Marilyn (courtesy of Christie’s)

Christie’s made headlines during its Spring Marquee Week when Andy Warhol’s “iconic portrait of Marilyn Monroe,” Shot Sage Blue Marilyn, sold to Larry Gagosian for a little over $195 million after just 4 minutes of bidding. This was the second-highest result for an artwork at auction, and the highest price ever paid for a work by an American artist. Notably, Gagosian had previously sold the work to Thomas Ammann in 1986, so the work is returning to its prior seller almost forty years later. (It is unclear whether Gagosian is keeping Marilyn for his own collection or whether he purchased it on behalf of a client.) Overall, the sale attracted bidders from 29 different countries and 68% of lots sold above their respective high estimates, demonstrating that collectors have not lost their appetite for contemporary art over the past two years. Works by six other artists, including Francesco Clemente and Ann Craven also sold for record prices while Cy Twombly and Robert Ryman occupied the top lots after Warhol. Christie’s Chairman of 20th and 21st Century Art, Alex Rotter, commented that this was a “historic night” and “a testament to the strength, the vibrancy, and the overall excitement of the art market today.”

Sotheby’s spring sales also broke records, with the second half of the Macklowe Collection up for grabs. Achieving a total of $922 Million, the Macklowe Collection won the distinction of becoming the most valuable collection ever sold at auction. The group of 65 works, including exemplars by Rothko, Warhol, Giacometti, and de Kooning, was sold during two separate auctions in the fall and spring (the first on November 15, 2021, and the second on May 16, 2022), driving up interest. The collection was formed by Harry B. Macklowe and his ex-wife Linda over the many decades of their marriage. In 2018, amidst acrimonious divorce proceedings and widely varying appraisals over the collection’s actual value, a New York State Supreme Court judge ordered the couple to sell the artworks and split the profits equally. Although the auctions were delayed due to Covid-19, it was well worth the wait.

Finally, a third big auction house player made headlines for astronomical prices this spring. Phillips’ superstar was an untitled work by Jean-Michel Basquiat. The acrylic and spray paint on canvas from 1982 was estimated to sell for $70 million, but it surpassed expectations and brought in $85 million during an evening sale on May 18, 2022. The seller, Japanese mogul Yusaku Maezawa, had originally purchased the 16-foot-long work in 2016 for $57.3 million. Basquiat is currently enjoying a resurgence in popularity among both established and younger art collectors, with another work selling for $40 million last November.

Finally, a third big auction house player made headlines for astronomical prices this spring. Phillips’ superstar was an untitled work by Jean-Michel Basquiat. The acrylic and spray paint on canvas from 1982 was estimated to sell for $70 million, but it surpassed expectations and brought in $85 million during an evening sale on May 18, 2022. The seller, Japanese mogul Yusaku Maezawa, had originally purchased the 16-foot-long work in 2016 for $57.3 million. Basquiat is currently enjoying a resurgence in popularity among both established and younger art collectors, with another work selling for $40 million last November.

Artsy noted that the 20th-century and contemporary art auctions reflect a “shift in collector’s interests across the board with women artists, artists of color, and emerging artists receiving both critical interest and incredible financial interest.” The staggering results for some of these artists (often realizing much larger amounts their high estimates) may be the result of collectors seeking to purchase works by artists with potentially long and successful careers whose values may further increase. Several news sources noted that one of the stars in this field is Anna Weyant. The 27-year-old Canadian had her works sold at the three major auction houses (Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Phillips) and high-profile galleries. Her work, “between sweet and sour, beautiful and foreboding” has surged in price and interest across the board.

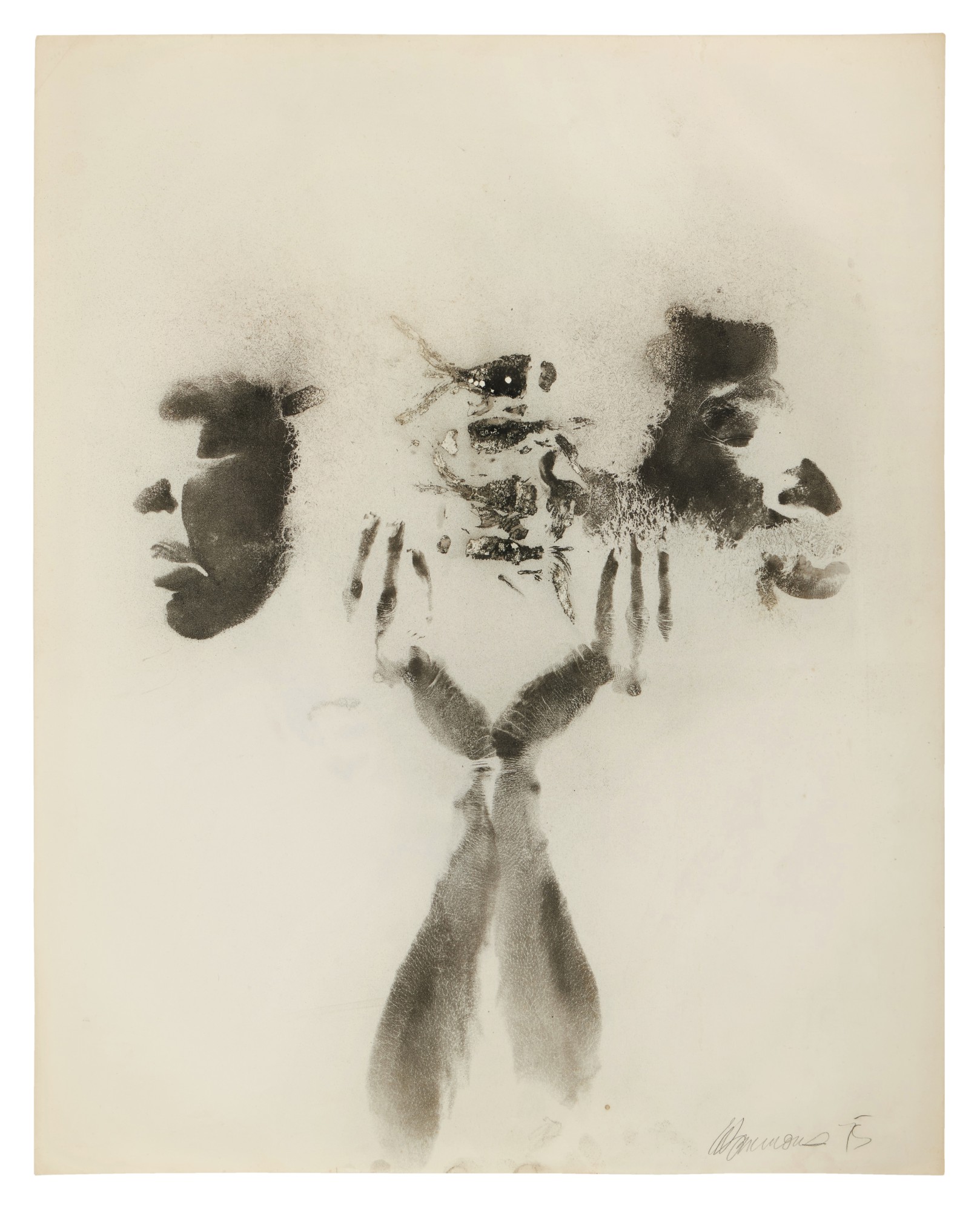

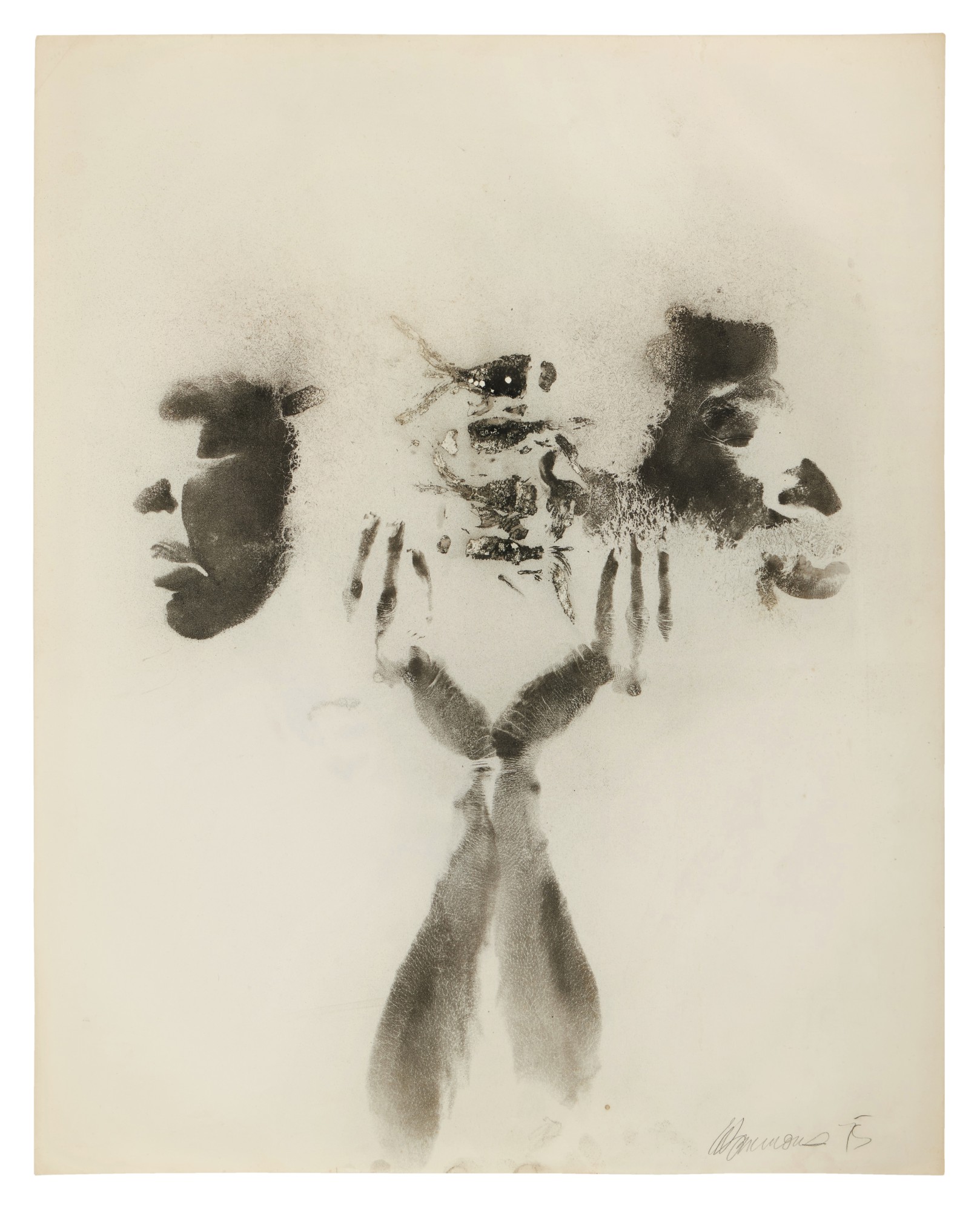

We were pleased to represent a number of collectors consigning important works at auction this spring. One of our clients is the collecting family that consigned three works by David Hammons for the Sotheby’s Contemporary Evening Auction on May 19. Sotheby’s touted these works and their provenance, after the paintings remaining with our clients for nearly five decades. All three of the works performed well, with two of them selling for above their high estimates. (The combined high estimate of the 3 works was $2.3 million, and they actually realized $2.6 million.)

We were pleased to represent a number of collectors consigning important works at auction this spring. One of our clients is the collecting family that consigned three works by David Hammons for the Sotheby’s Contemporary Evening Auction on May 19. Sotheby’s touted these works and their provenance, after the paintings remaining with our clients for nearly five decades. All three of the works performed well, with two of them selling for above their high estimates. (The combined high estimate of the 3 works was $2.3 million, and they actually realized $2.6 million.)

It is always gratifying to work with clients and help them achieve the best outcomes for the sale of artwork. We look forward to a continued season of strong art market sales and new and exciting artists as summer approaches.

Of course, this is devastating news to families seeking to reclaim an important piece of family heritage. If a museum denies heirs’ claims, they may proceed to file litigation. One high-profile example is Gustav Klimt’s portrait of Maria Altmann, titled

Of course, this is devastating news to families seeking to reclaim an important piece of family heritage. If a museum denies heirs’ claims, they may proceed to file litigation. One high-profile example is Gustav Klimt’s portrait of Maria Altmann, titled  Decades of case law in the U.S. indicate the difficulties facing claimants. Recent cases against New York museums resulted in wins for the institutions, yet not due to the merits of each respective case. Rather, the Museum of Modern Art squeaked out wins through a confidential

Decades of case law in the U.S. indicate the difficulties facing claimants. Recent cases against New York museums resulted in wins for the institutions, yet not due to the merits of each respective case. Rather, the Museum of Modern Art squeaked out wins through a confidential

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4

Finally, a third big auction house player made headlines for astronomical prices this spring. Phillips’ superstar was an untitled work by Jean-Michel Basquiat. The acrylic and spray paint on canvas from 1982 was estimated to sell for $70 million, but it surpassed expectations and brought in

Finally, a third big auction house player made headlines for astronomical prices this spring. Phillips’ superstar was an untitled work by Jean-Michel Basquiat. The acrylic and spray paint on canvas from 1982 was estimated to sell for $70 million, but it surpassed expectations and brought in  We were pleased to represent a number of collectors consigning important works at auction this spring. One of our clients is the collecting family that consigned three works by David Hammons for the Sotheby’s Contemporary Evening Auction on May 19. Sotheby’s

We were pleased to represent a number of collectors consigning important works at auction this spring. One of our clients is the collecting family that consigned three works by David Hammons for the Sotheby’s Contemporary Evening Auction on May 19. Sotheby’s