Dispute of Looted Violin Reaches Crescendo, Highlighting Difficulties in Restituting Plundered Instruments

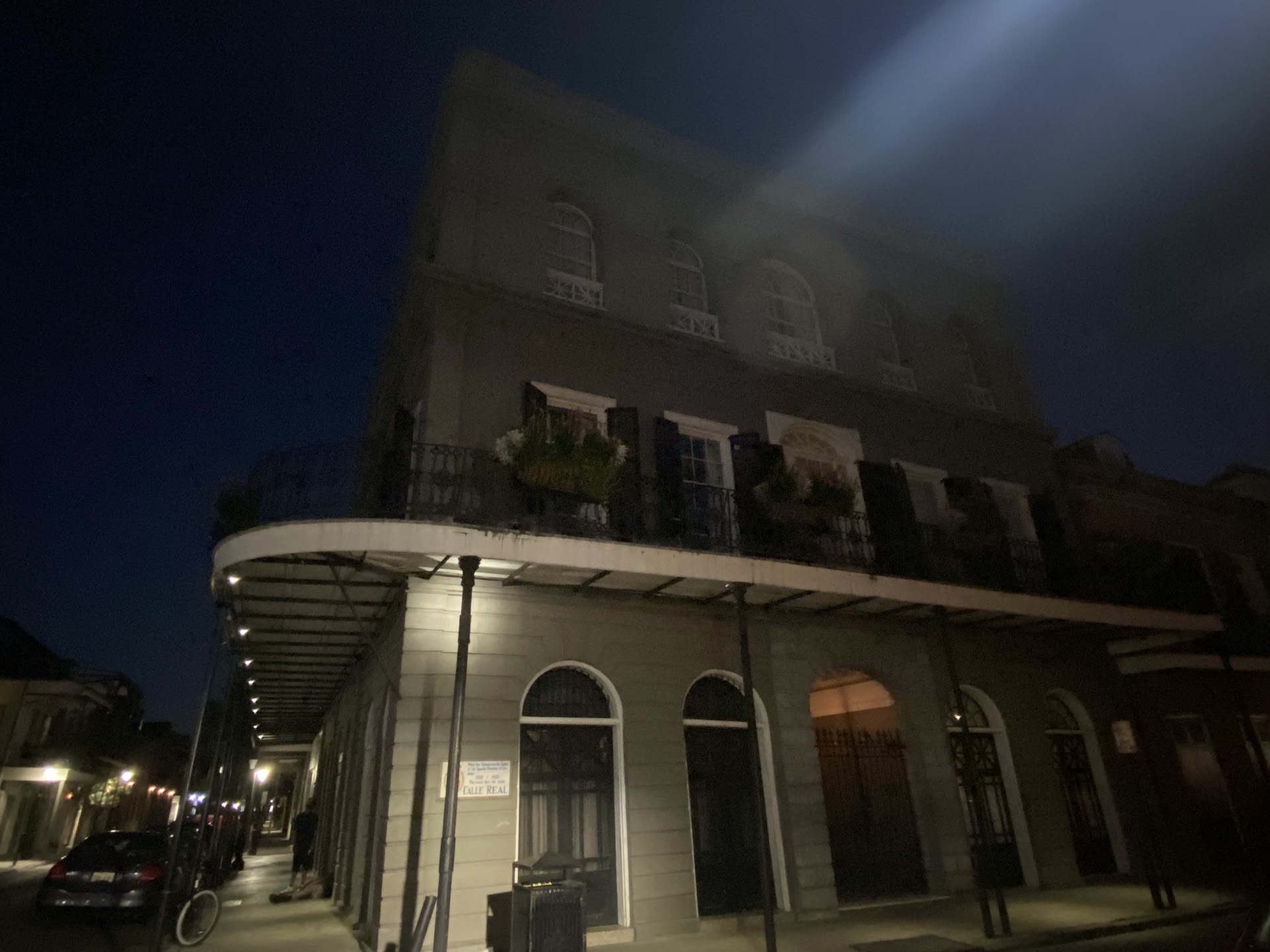

View of a train boxcar with an art collection looted by the Nazis, near Berchtesgaden, Germany, 1945. (Photo: William Vandivert/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images)

It has been estimated that the Nazi Party looted 20% of all art in Europe. The Nazis not only confiscated and stole property, but also forced victims to sell items at a fraction of their worth, pay exorbitant flight taxes, or abandon their homes and property when fleeing from the Third Reich. The toll of deprivation on such a massive scale is still felt many decades later. In recent years, multi-million dollar restitutions and disputes over valuable works have drawn interest from the international community. (Information about some of the landmark cases in this area can be found in an earlier entry in our Provenance Series.) One famous instance was the 2013 discovery of 1,500 works in a Munich flat belonging to Cornelius Gurlitt, the son of a notorious art dealer employed by the Third Reich. His infamous collection included works by artists such as Picasso, Monet, Matisse, and Chagall, some of them stolen. To date, the German government has identified only 14 works from the Gurlitt trove as definitively looted. Some of them have been returned to rightful heirs, purportedly signaling Germany’s “lasting commitment” to the repatriation of Nazi loot.

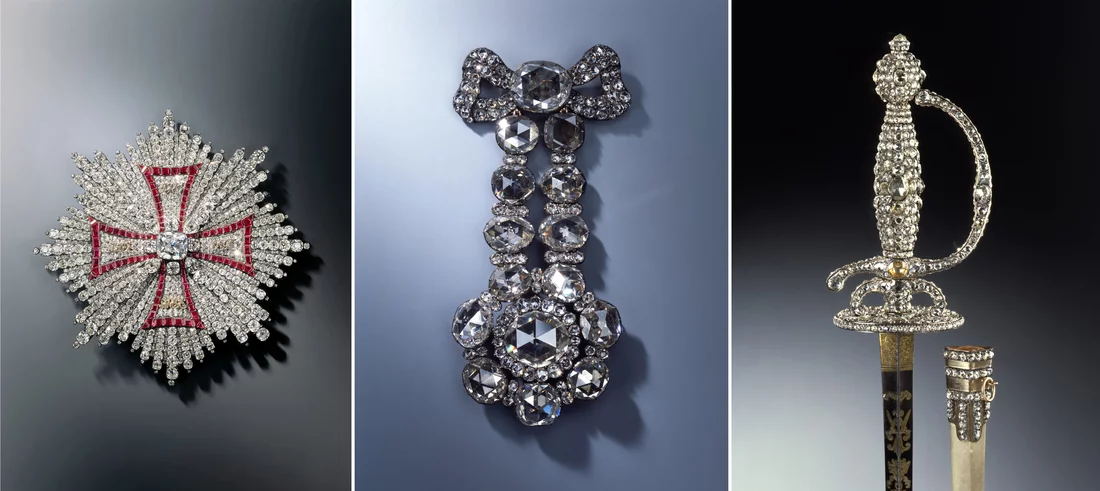

Over the years, Nazi-looted artwork has also made its way to other continents. One of the best-known legal battles concerning Nazi plundered art, Republic of Austria v. Altmann, 541 U.S. 677 (2004), was featured in the Hollywood film The Woman in Gold. The movie traced the provenance and legal battle for ownership of a collection of works by Austrian Painter Gustav Klimt, including a gilded portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer. The case made its way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, which led to the dispute being arbitrated in Austria. Five of the six valuable works in question were returned to the rightful owners, the heirs of the original owner. This year, the U.S. Supreme Court is poised to make a decision concerning the disposition of a valuable collection of medieval objects known as the Guelph Treasure. Far from being relegated to the past, the shadow of the Third Reich continues to haunt people across the globe more than 75 years after WWII came to an end.

The lack of a centralized authority or a uniform approach to restitution cases is an additional hurdle. In order to address the particular issues relating to Nazi-confiscated art, a series of forty-four non-binding principles known as the Washington Principles were developed in 1998. The Principles were drafted after the scale and severity of Nazi plunder became known to the public, partly due to previously private records released after the end of the Cold War. They have since been a useful tool for the return of looted property, based upon moral and ethical concerns. However, their non-binding nature means that voluntary cooperation is crucial for their implementation. Enforcement of the Washington Principles thus relies on public pressure and moral appeals rather than a strict duty to act. This can cause friction or a stalemate when the current possessors of Nazi-looted property do not wish to return items or compensate the heirs of the families from which the items were taken.

NAZI LOOTING BEYOND FINE ART

A Lódz ghetto official registers violins brought to the ghetto bank. The violins were shipped to Germany

Photo: From the archives of Yivo Institute for Jewish Research, New York

Nazi plunder was not limited to fine art. The Nazis also looted movable objects such as gold, silver, currency, musical instruments, religious items, furniture, books, ceramics, household items, photos, and countless personal effects. These items are not publicized as often because their values are generally not as high. However, these objects are often more susceptible to theft and subsequent sales, partly because they are difficult to trace, making recovery elusive. The Lost Music Project has dedicated themselves to conducting research on musical material lost during the Nazi era, and filling in the gaps for looted, confiscated, and displaced items. According to newly declassified documents, the Nazis deliberately targeted musical instruments belonging to Jewish owners. Priceless violins, including those by master craftsman Antonio Stradivari, were among the myriad of confiscated items.

The German documents obtained by the Chicago Tribune relate how Nazi forces were accompanied by musicologists, forming a Special Task Force for Music. The music experts carefully evaluated, catalogued, and prepared the best stolen instruments and other musical items for transport. This process took place under direct orders from Adolf Hitler himself, to obtain the instruments of highest artistic value for immediate relocation to Berlin. The campaign ran for five years, beginning in 1940, and was integrated into the war effort. For instance, bands playing looted instruments would welcome crews from Nazi submarines. There is a single surviving copy of an inventory list detailing the finest stolen instruments that had been confiscated, which mentions 75 antique stringed instruments, or “casualties of war.” Thousands of pianos were also stolen, and the vast majority of these are still unclaimed or at large.

Identifying and recovering looted musical instruments is no easy feat. Smaller instruments which are portable by nature, such as violins, are relatively easy to remove and hide. Furthermore, the international rare instrument trade has typically operated under limited public scrutiny, and dealers have sometimes failed to make thorough provenance checks before reselling items. Instruments are more difficult to identify than works of art, and documentation such as bills of sale or certificates of authenticity are not always available. Likewise, personal correspondence and photographs are rare. Carla Shapreau at the Lost Music Project has spent the last decade tracking down Nazi-looted instruments. She states that it is extremely challenging to find stolen instruments due to the fact that available documentation is both scarce and scattered across many countries. Such information has generally been inaccessible until recently, further muddying the waters. As additional plundered instruments come to light, unpleasant questions must be asked before restitution can take place. While the issue is gaining traction in the public sphere, reckoning with the past is not always straightforward, as demonstrated by the case discussed below.

THE FIRST DISPUTE OVER A MUSICAL INSTRUMENT

Illustration in book about Casa Guarneri (1906)

Fittingly, the first dispute over a Nazi-looted musical instrument arose in Germany. At the center of the case is a 300-year old violin crafted by Cremonese master Giuseppe Giovanni Battista Guarneri (better known as Giuseppe ‘filius Andreae’ Guarneri) purchased by Jewish music supply dealer Felix Hildesheimer from Hamma & Co. in Stuttgart, Germany in 1938. Its whereabouts prior to that date are currently unknown, although Guarneri violins have a fascinating history. Instruments bearing the Guarneri name are considered as precious as those by Antonio Stradivari, and valued at millions of dollars. Compared to Stradivari violins, which perform best in higher ranges, Guarneri violins are prized by musicians for delivering a deeper, more robust sound. This is attributed, in part, to innovations introduced by Giuseppe after he inherited his father’s renowned violin business in 1698. Not content to merely follow his father’s designs, his use of rounded upper bouts and tilted f-holes denote originality to complement his master craftsmanship. Although highly regarded today, Giuseppe’s life was spent in the shadow of Stradivari; where Stradivari patrons included kings and dukes, Guarneri violins were sold locally to practicing musicians. This contrast was made all the more apparent as both luthiers sold their creations from the Piazza San Domenico in Cremona, Italy. Giuseppe’s willingness to innovate, however, imbued his violins with full arch and a carrying power not seen in Stradivari’s work for another 20 years.

These violins are not only functional, but beautiful as well as historically and culturally significant. Like many such cases, the core of the recent Guarnieri violin dispute touches upon both non-legal and legal issues concerning ownership and provenance. Shortly after Hildesheimer purchased the violin, he was forced to sell his home and music store. He would eventually take his own life in 1939, survived by his wife and daughters who emigrated abroad to start over.

Tragically, stories like Hildesheimer’s were common during the reign of the Third Reich. They demonstrate a concerted effort to deprive Jewish victims of property under false pretenses. Despite these efforts, diligent research has made it possible to trace the path of the violin following the purported forced sale. The violin effectively disappeared for over 30 years. Then in 1974 it was rediscovered in disrepair in a shop in Cologne, Germany by violinist Sophie Hagemann. Unaware of its troubled history, it is serendipitous that Hagemann then used the violin as part of the music group Duo Modern to play music labeled as “degenerate” and banned during the Nazi regime. The violin remained in Hagemann’s possession until her death in 2010, at which point it passed to the Franz Hofmann and Sophie Hagemann Foundation (Franz Hofmann, Hagemann’s husband, was a composer who died in 1945). The Foundation claims to have received the violin in poor condition, requiring restoration. Eight years ago, the violin was valued at $185,000. The Foundation also conducted an investigation into the violin’s provenance, recognizing that the gap in ownership between 1939 and 1974 was a source of concern. Ownership was eventually traced back to Hildesheimer, at which point the Foundation sought to “proactively clarify” any potential restitution claims by contacting Hildesheimer’s descendants. In spite of these early efforts to amicably resolve a potential dispute, interaction between the Foundation and the heirs became strained over time.

The German government’s Advisory Commission on the Return of Cultural Property Seized as a Result of Nazi Persecution was called to review the dispute in 2015. The Commission seeks to bring the Washington Principles into practice. It may be called upon to assist in the resolution of disputes concerning the return of cultural assets seized from their owners as a result of Nazi persecution. A request for intervention may be filed by a former owner, heirs, or institutions and individuals currently in possession of the relevant cultural asset. The Commission works toward amicable settlements between the parties, who must agree to enter into mediation. The Committee ultimately issues a non-binding recommendation. In 2016, the Commission determined that the violin had either been sold under duress or seized by the Nazis after Hildesheimer’s death. The panel recommended that the Foundation maintain possession of the instrument and pay $120,000 to the dealer’s descendants as compensation.

Both sides initially accepted the recommendation as a fair and equitable solution; however, the Foundation now refuses to comply. Although it first claimed that it could not raise the funds to meet the allotted amount, the Foundation issued a statement on January 21, 2021 challenging the Commission’s recommendation. According to the Foundation, new information suggests that the violin was not the subject of a forced sale, meaning that it was not looted by the Nazis and falls outside of the Commission’s scope. The Commission responded by issuing a public statement condemning the Foundation’s actions as “not just contravening existing principles on the restitution of Nazi-looted art… [but] also ignoring accepted facts about life in Nazi Germany.”

FORCED SALES

Picasso’s “The Actor.” Credit: Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ultimately, the Commission cannot compel the Foundation to honor its recommendation. Furthermore, the Foundation’s argument raises the question as to whether all sales made during the Nazi regime should be considered coerced or forced, or if there is the possibility that some transactions were voluntary. This topic has arisen in the past, recently in Zuckerman v. Metro. Museum of Art, 928 F.3d 186 (2nd Cir. 2019). Zuckerman raised issues about the definition of duress, and it was one of the first cases decided after the passage of the U.S. Holocaust Era Art Restitution (HEAR) Act of 2016. There, the great-grandniece of a German-Jewish art collector sought to recover a Picasso painting from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The plaintiffs alleged that the painting was sold under duress in 1938 when the owners fled Fascist Italy. The work was eventually donated to the Met in 1952 by a subsequent purchaser. The Southern District of N.Y. dismissed the case, ruling that the Leffmanns’ sale of the Picasso was not be considered a “forced sale” or made “under duress.” The plaintiffs appealed, but the Second Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed and dismissed the case on statute of limitations grounds. The court ruled that the plaintiffs had waited too long to file a complaint to recover a work that had been on public display (in one of the world’s most visited museums) for decades. As such, the court did not provide a definitive answer as to what comprises a forced sale or sale under duress.

Like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Zuckerman, the Foundation claims there is no proof that the sale of the violin was made under duress. However, the Nazi Party was well-known for “persuading” Jewish citizens to hand over their property under the Nuremberg Laws. The timing of the violin’s disappearance is suspect. Unusually, the Foundation admitted that the provenance of the violin is incomplete, it took the initiative to contact Hildesheimer’s heirs, and it even requested intervention by the Commission. This seems to indicate the Foundation’s tacit acknowledgment that the movement of the violin is problematic or at least it requires heightened scrutiny. The sudden reversal of the Foundation’s attitude is surprising.

REFUSING TO COMPLY WITH RESTITUTION DETERMINATIONS

The Foundation’s refusal to comply with the Commission’s recommendation illustrates the inherent problem in relying on voluntary cooperation for restitution cases. In the absence of a legally binding decision, such as those issued in a court of law, parties may ignore determinations. Such open and notorious refusal to comply threatens the Commission’s status and could seriously undermine its ability to resolve similar disputes moving forward. In the words of Hildesheimer’s grandson, “If the commission can be defied with no consequences, I don’t see how these cases can be dealt with in [the] future.” Most institutions and private parties have been unwilling to risk the negative press that follows noncompliance with a Commission determination. If the Foundation can weather criticism without consequence, it could set an ignoble precedent and embolden similarly situated parties to defy the Commission. However, there is still time for the Foundation to change its tune, and political pressure or moral principles may sway the Foundation to implement the Commission’s recommendation and support Germany’s restitution policy.

Tracking down and recovering Nazi-looted art and objects is extremely challenging. Not only have countless items been lost, damaged, or destroyed without a trace, but musical instruments have their own lives and personalities, echoing their previous owners. In the words of the late Elan Steinberg, former executive director of the World Jewish Congress: “There is something more emotional and personal when you start to talk about items such as musical instruments… A bank account, an insurance policy – those are material assets. A violin was played by someone. So what we have involved here is not simply the stealing of property but the stealing of memories and humanity. In a very real sense, this is more brutal than financial theft. It’s about erasing identity.”

TROUBLES WITH NOTABLE INSTRUMENTS

Joseph Goebbels, presenting the gifted violin to Nejiko Suwa in 1943. Credit: Cegesoma Bruxelles

The story of another famous violin echoes many of the same challenges discussed above, despite the instrument having been subject to public scrutiny for over 50 years. In 1943, German Minister for Propaganda Joseph Goebbels gifted a Stradivari violin to a 23-year-old Japanese prodigy, Nejiko Suwa. Despite the Nazis’ prolific record keeping, it is unclear how Goebbels acquired the violin, leading many to suspect it was confiscated or purchased under duress. After returning to Japan with the violin, a contemporary critic openly challenged Ms. Suwa to “let decency as a human being overcome your love as an artist, shake off your tears, and make a firm decision to return this violin to the former owner on your own accord.” Ms. Suwa, who died in 2012, publicly contradicted any claims that the violin had been unethically sourced, arguing that it was legally purchased by Goebbels’ ministry. The absence of information about its previous owners is sadly not uncommon for instruments that passed through Nazi possession. Goebbels was known for equipping prominent musicians with master-crafted instruments, so long as they comported with Nazi standards of decency; plundered instruments would have provided an all too convenient means of sourcing these gifts. The use of instruments in this way highlights their cultural significance, and they were used to aid in Goebbels’ effort to alter the cultural fabric of Europe.

This particular gift would become inseparable from its new owner, as Ms. Suwa protected the violin as she moved across the war-torn continent. “I have risked my life to protect it,” she was quoted years later. After the Second World War, Ms. Suwa was the first Japanese musical star to perform in the U.S., participating in a benefit concert at the Hollywood Bowl. During the performance, she used her gifted violin to play Violin Concerto in E Minor by Mendelssohn, a composer who had been blacklisted during Nazi rule. The violin’s use for this repertoire sent a message about the Nazi’s cultural restrictions, but its continued possession by Ms. Suwa leaves a morally conflicted legacy. The violin is now held by Ms. Suwa’s nephew, who declined to discuss specifics about the future of the instrument. The lack of information about prior ownership and the absence of a more effective restitution effort leaves the fate of these precious and culturally important objects in question.

CHALLENGES POSED BY RESTITUTION CLAIMS

There are various challenges tied to the restitution of Nazi-looted art and objects. The lack of evidence or living witnesses, as well as the lack of proof concerning the circumstances of a sale or seizure that occurred decades ago, mean that definitively proving ownership is difficult. In some cases, heirs may not even be aware of their families’ previous collections or any viable legal claims they may possess, whether in the U.S. or abroad. Artworks not included in catalogues raisonnés or referenced in an artist’s biography or correspondence are especially difficult to trace. For instance, without references to their individual characteristics, Guarneri violins could be nearly impossible to distinguish from one another. Movable items, including musical instruments, jewelry, and furniture, may have been damaged, disassembled, covered with paint or varnish, or otherwise modified after their last known appearance. Under this camouflage, Nazi plunder may be hiding in plain sight.

Nonetheless, while progress in recovering these items may be slow, ownership disputes continue. The Foundation’s posturing over compensation threatens the hard-won recommendations issued by the Commission and delays potential justice for the heirs of dispossessed Jewish families. As this is the first musical instrument case to come before the Commission, the precedent is troubling. We will follow the case with great interest in hopes that a fair and just solution may be found.