The Earliest Nativity Scenes and a Nativity Theft (Provenance Series: Part XII)

Nativity scenes – or depictions of the Holy Family, angels and shepherds adoring the newborn Jesus – are common in Christian iconography, particularly during the Christmas season. Italian churches often commemorate the holiday with elaborate nativity scenes, or...Checkmate- Famed Chess Pieces Across the Ages (Provenance Series: Part XI)

The Chess Game, Sofonisba Anguissola (1555 – National Museum Poznań)

The Queen’s Gambit on Netflix has recently been credited with helping to fuel a chess renaissance. The series about an orphan with a preternatural mastery of chess features a beautiful wardrobe for its main protagonist, 1960s music, and high-stakes international tournaments. With the onset of winter and a second round of lockdown looming over many countries, people are turning to games – such as chess – for a respite. Sales of chess sets and accessories have skyrocketed as much as 215%, with interest mainly in wooden and vintage sets. Millions are subscribing to and playing matches on websites, breaking existing records.

However, chess’ popularity predates the current craze. For centuries, military strategists, royalty, children and others have enjoyed this board game, which is one of the oldest in the world. Chess is believed to have originated in northwest India before spreading along the Silk Road, eventually reaching Western Europe via Persia and Islamic Iberia. The oldest archaeological chess artifacts, made of ivory, were excavated in Uzbekistan and date to approximately 760 A.D. Chess has been depicted in numerous artworks, literature, and films, including a memorable match in the Harry Potter franchise and a painting by Sofonisba Anguissola (pictured above).

Lewis Chessman (Photo: British Museum)

Antique chess pieces are not only historically important, but also offer a fascinating glimpse into artistic, commercial, and cultural trends. The Lewis Chessmen, discovered in 1831, are possibly the finest known example of medieval European ivory chess pieces. They are believed to be the first chess pieces to depict bishops and they possess distinctly human forms. The set was discovered on the island of Lewis in Scotland, as part of a hoard containing 93 artifacts in total. The pieces date back to the 12th or 13th century, with 82 pieces forming part of the British Museum’s collection and 11 pieces held by National Museums Scotland. The chess pieces were likely made in Trondheim, Norway from walrus ivory and teeth. They exhibit many interesting details, such as bulging eyes and a rook (depicted as a standing soldier or “warder”) biting its shield like a Viking berserker. The pieces reflect the ties between Scandinavia and Scotland at the time the carvings were made. Interestingly, the Lewis Chessmen were among the first medieval antiquities acquired by the British Museum, and they have also been featured as #61 in the 2010 BBC Radio series A History of the World in 100 Objects.

As with all artwork and artifacts, provenance is extremely important. In fact, if may even be more important for chess pieces, which are portable in nature and thus prone to separation and forgery. It is rare for entire sets to survive intact; some pieces in circulation are even high-profile copies of masterpieces, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s reproductions. The Met’s collection even includes copies of certain Lewis Chessmen. The Lewis pieces’ provenance prior to its discovery in 1831 is unknown, although they may have been the property of a merchant or a local leader, buried for safeguarding or for future trade with Iceland. In fact, there are conflicting accounts of their discovery. Supposedly, Malcolm MacLeod discovered the trove in a dune, exhibited the chess set for a brief period, and then sold the pieces to Captain Roderick Ryrie. Ryrie then exhibited the pieces at a meeting of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in April 1831, and the set was split up shortly after. Ultimately, the British Museum purchased the majority of the pieces for £84 on the recommendation of chess enthusiast Sir Frederic Madden. This proved to be a solid investment, as one of the chess set’s related pieces (a previously unrecognized warder) was sold in July 2019 at Sotheby’s for £735,000. It had been bought by an antiques dealer in Edinburgh for £5 fifty-five years before, and the dealer’s family had no idea of the object’s importance until the family submitted it for appraisal. The warder was described as “characterful” and as having “real presence” by Sotheby’s expert Alexander Kader.

Man Ray Chess Set

While the Lewis Chessmen are exceptional, they are not the only chess sets to have achieved fame. The Charlemagne Chess Set, currently held by the National Library of France in Paris, was made in Salerno, Italy in the late 11th century. It formed part of the treasury of the Basilica of Saint Denis and has unusual dimensions. The set is seen as symbolic, depicting the various roles of individuals in medieval society. Yet despite its name, it never belonged to Charlemagne. And unfortunately, only 16 pieces are left from the 30 inventoried in the 16th century. The Àger chess pieces are another unique example of the game, as they were crafted from rock crystal. Believed to have been made in Egypt, Iraq or eastern Iraq during the 9th century, they were deposited in the Àger monastery in present-day Catalonia, Spain during the 11th century. As the chess set has an Islamic origin, the pieces are not humans but rather present an abstract style with arabesque decorations. Finally, Surrealist artist Man Ray produced a modern design for a chess set inspired by everyday objects. These were then reduced to simple, semi-abstract forms: the knight was represented by a violin scroll, the bishop by a flask, and the king by an Egyptian pyramid. Reproductions of Man Ray’s are available to players at all price points.

We hope you have enjoyed this journey through the fascinating world of chess. Amineddoleh & Associates is proud to represent collectors in pursuing their creative passions, whether that is through the sale of artwork or by acquiring antique board games that display craftsmanship and historical value. Collectors should always remember to perform due diligence and consult experienced legal professionals when considering art and cultural property-related transactions.

Ghoulish Art and Demonic Works: Provenance Series (Part XI)

Stories of ghosts, demons, and other horrors are common to all cultures, and most cultures around the world have art portraying the supernatural. Since ancient times, Japan’s religion and culture has been deeply bound with ghosts, called yūrei. Both feared and revered, yūrei are part of the deep magic; a foundational belief that humans have a god inside of them.

Stories of ghosts, demons, and other horrors are common to all cultures, and most cultures around the world have art portraying the supernatural. Since ancient times, Japan’s religion and culture has been deeply bound with ghosts, called yūrei. Both feared and revered, yūrei are part of the deep magic; a foundational belief that humans have a god inside of them.

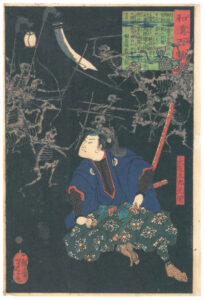

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, born in 1839 in Japan, is known as one of the last great masters of the Japanese woodblock print. One of his masterpieces a series of works, 100 Ghost Stories from China and Japan. The series, created in 1865, includes images of skeletons, ghosts, and other supernatural creatures. One well-known print is Japanese samurai warrior, Oya Taro Mitsukuni watching a battle scene between armies of skeletons.

Leizhen (Raishin), MFA Boston

The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (MFA) owns Leizhen (Raishin), from the series. The work, signed by Ikkaisai Yoshitoshi ga, was purchased by William Sturgis Bigelow in 1911 and then gifted to the MFA. Bigelow was a prominent American collector of Japanese art. He lived in Japan for seven years. The Japanese government authorized him and two other Americans to explore parts of Japan that had been closed to outside viewers for centuries. During his time there, he acquired valuable art, including the mandala from the Hokke-do of Tōdai-ji, one of the oldest Japanese paintings to ever leave Japan. Bigelow donated approximately 75,000 objects of Japanese art to Boston MFA. Due to the huge donation, the still has the largest collection of Japanese art anywhere outside Japan.

Perhaps even more haunting is a series of fourteen works, the Pinturas Negras (Black Paintings), created between 1819 and 1823 by Spanish painter Francisco Goya. The works depict dark themes that reflected Goya’s own fears and his bleak view of humanity, in part due to the fact that the Spanish master was going deaf. At the age of 72, Goya moved into a home outside of Madrid known as La Quinta del Sordo (the Deaf Man’s Villa). The previous owner was deaf, and Goya was nearly deaf by the time he moved into the home. During this despairing time, Goya painted a series of unsettling works, such as murals on the walls of his house. They were eventually transferred to canvas.

Witches’ Sabbath, El Prado

One of the most macabre is the work now known (Goya did not title the murals) as the Witches’ Sabbath (El Aquelarre) or The Great He-Goat (El Gran Cabrón). Like most of the other works in the series, it was painted with dark and earth-toned colors. The painting depicts a witches Sabbath attended by the Devil in the form of a goat. The He-Goat appears as a silhouette painted entirely in black, except for one eye. Facing the demonic creature is a coven of witches and warlocks, portrayed with hideous features. The series of works was acquired by the Baron Emile d’Erlanger when he purchased the “Quinta” in 1873. He had the murals transferred to canvas, but they suffered great damage. The Baron ultimately donated the works to the government of Spain, which in turn moved them to the Prado, a national museum located in Madrid, to be publicly viewed.

The portrayal of devils and demons in works of art dates back millennia. Featured in The Exorcist, Pazuzu is the main antagonist who is exorcized from its victim. But the demon was not just the creation of the author of the The Exorcist, William Peter Blatty. The demon derives from Assyrian and Babylonian mythology, where it was considered the king of the demons of the wind, and the son of the god Hanbi.

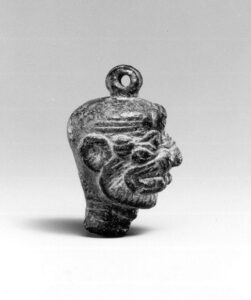

Pendant of Pazuzu, Metropolitan Museum of Art

On display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (the Met) is a small pendant of the demon, dating from the 8th to 7th century BC. The pendant has bulging eyes, bulbous forehead protrusions, and short beard that rings the snarling open mouth, atop an incongruously thin neck. These are his unmistakable features.

According to the Met, Pazuzu appears on many plaques and amulets, sometimes as a figure with wings and a scorpion tail. The earliest image of Pazuzu dates to the late 8th century B.C., relatively late in the history of demonic imagery in Mesopotamia. The museum states that this was a period when the Assyrian royal administration was intensely focused on collecting magical knowledge and studying the supernatural world, and priests and exorcists were actively engaged in codifying these systems of knowledge. As a result, a rich variety of magical images and texts from Assyria in this period have survived. The pendant was sold at Hôtel Drouot, Paris, on May 19-20, 1987, and eventually it was acquired by the museum in 1993, purchased at Sotheby’s New York, on June 12, 1993.

In addition to the demonic pendant, the Met owns other spooky art, including this photograph of a ghostly apparition.

Horrifying Provenance of Monster Manuscripts: Provenance Series (Part X)

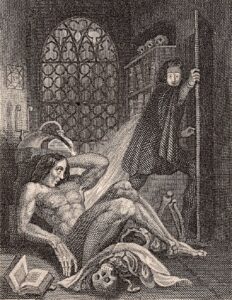

Illustration from the frontispiece of the revised edition of Frankenstein, published by Colburn and Bentley, London 1831.

Some of Hollywood’s most famous “monsters,” jumped off the pages of Gothic novels to the excitement and fear of spellbound readers. One of the most famous is the monster from Frankenstein. At the young age of just 18, Mary Shelley created a tale that would fill readers with dread, as well as empathy. Frankenstein, the Modern Prometheus, was a being imbued with humanity seeking love and acceptance. The teenage Mary Shelley created her tale during a ghost-story competition one stormy evening in the summer of 1816 while on holiday in Switzerland with Percy Shelley, Lord Byron, Claire Clairmont and John Polidori. During the course of her edits, the “monster” evolved from a “being” to a more human creature, and the book was first published in 1818.

As Mary Shelley’s horror story shaped Gothic literature, her copious notes and edits have been studied by historians, academics, and fans of the novel. The pages are now available online to viewers around the world on the Shelley–Godwin Archive. The original transcript is currently in the Bodleian Libraries at Oxford as part of the Abinger Collection. The collection was given to the university, in batches between 1974 and 1993, by James Scarlett, 8th Lord Abinger.

The Abinger papers are the residue of the collection of the Shelley family’s papers from Boscombe Manor (near Bournemouth, Dorset), the home of Sir Percy Florence Shelley, 3rd Baronet of Castle Goring (1819-1889), and his wife Jane, Lady Shelley (1820-1899). Sir Percy had inherited the family archive from his mother, Mary Shelley. She maintained papers from her parents, her husband, and from her own writing.

Villa Diodati, near Geneva, where literary character Frankenstein was created in 1816. (Credit: DeAgostini/Getty Images)

Since Mary Shelley had a close relationship with her daughter-in-law, it was Lady Shelley (Jane Shalley) who cared for and acquired additional items for the family archive. After her husband’s death, Lady Shelley endowed the Shelley Memorial at University College (1893) and she gave selected notebooks, letters and relics to the Bodleian Library (1893 and 1894). She bequeathed most of Mary Shelley’s other notebooks, relics, and papers to her husband’s cousin and the heir to his baronetcy, John Courtown Edward Shelley, later known Sir John Shelley-Rolls (1871-1951). Sir John gave the notebooks to the Bodleian Library in 1946.

Jane Shelley bequeathed her houses with their residual contents to her two eldest grandsons, Shelley and Robert Scarlett. Eventually, Shelley and Robert became respectively the 5th and 6th Barons Abinger, both childless. The majority of the papers were passed to their brother Hugh, the 7th Baron Abinger. When Hugh’s son James became the 8th Baron Abinger in 1943, he took a serious interest in the family papers. In the early 1970s, Lord Abinger gave permission for the Shelleys’ joint journal to be prepared for publication by Oxford University Press, and deposited the original journals at the Bodleian for the editors’ use. This led to Lord Abinger’s decision to provide the entire collection on long-term loan at the Bodleian in nine batches between 1974-1993.

Lord Abinger’s son James succeeded him in 2002. He put the papers on the market, but gave the right of first refusal to the Bodleian Library. The library launched a campaign to raise the funds. This mission was accomplished in 2004, when the Abinger collection was bought outright by the Bodleian Library with donations from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the Carl and Lily Pforzheimer Foundation, and many other institutional and individual donors. Cataloguing of the papers was completed in 2010 with the aid of a grant from the John R. Murray Charitable Trust.

The information presented in this post can be found HERE.

Vlad Tepes dining while surrounded by the impaled bodies of his enemies; hence, the name “Vlad the Impaler.”

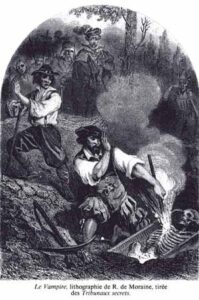

Another horror novel that has haunted generations of readers is Dracula. Inspired by tales of ruthless acts of violence and revenge exacted upon the Ottoman enemies of Vlad III (Vlad the Impaler, Vlad Tepes, or Vlad Dracula), Bram Stoker portrayed the Romanian ruler as a vampire and incorporated Romanian folklore about vampires in his novel. Written between 1890 and 1897, it is Stoker’s best known work. Count Dracula is one of the most filmed characters, and the tale has inspired countless other works, films, theatrical productions, and cultural references.

Nevertheless, the original manuscript had disappeared for decades. In a story worthy of the famous Gothic novel, the manuscript was lost and eventually found. In the 1980s, the heirs of Thomas Corwin Donaldson (a friend of both Bram Stoker and Walt Whitman) unearthed the manuscript of Dracula in a barn in Pennsylvania. Donaldson’s heirs sold the papers and manuscript through Peter Howard of Serendipity Books in Berkeley, California. Howard offered it to another book dealer and collector, John McLaughlin (owner of The Book Sail in Orange County, California). McLaughlin’s 1984 catalog lists the manuscript. Due to financial concerns, in 2002, McLaughlin consigned the manuscript to auction at Christie’s in New York.

The manuscript is complete with Stoker’s original handwritten title, The Un-Dead (Stoker changed the title only days before the publication in 1897). The manuscript failed to sell went it went to auction in 2002 at Christie’s in NY. It is signed or initialled by Stoker in many places and contains a different ending to the final one published in 1897, and it was expected to fetch £1m. Since it failed to reach its undisclosed reserve price, it did not sell at auction. However, the novel was later sold privately through Christie’s to Paul G. Allen, co-founder of Microsoft. Allen passed away in 2018, and the manuscript presumably remains in his estate.

The manuscript is complete with Stoker’s original handwritten title, The Un-Dead (Stoker changed the title only days before the publication in 1897). The manuscript failed to sell went it went to auction in 2002 at Christie’s in NY. It is signed or initialled by Stoker in many places and contains a different ending to the final one published in 1897, and it was expected to fetch £1m. Since it failed to reach its undisclosed reserve price, it did not sell at auction. However, the novel was later sold privately through Christie’s to Paul G. Allen, co-founder of Microsoft. Allen passed away in 2018, and the manuscript presumably remains in his estate.