by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 5, 2021 |

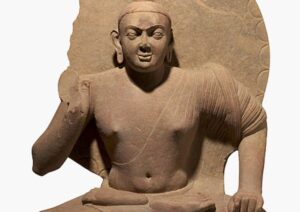

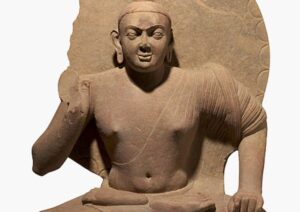

Indian relief seized from the Nancy Wiener Gallery in Manhattan.

(Photo Credit…Manhattan District Attorney’s Office)

Our founder, Leila A. Amineddoleh, spoke with the New York Times today about important revelations from statements submitted to the New York County Supreme Court by antiquities dealer Nancy Wiener during the pending criminal case against her. After pleading guilty to charges of conspiracy and possession of stolen property in connection with the trafficking of looted treasures from India and Southeast Asia, Ms. Wiener filed an allocution statement that reveals the inner workings of the antiquities market. (After pleading guilty, a defendant is often offered an opportunity to address the court in a so-called allocution statement to accept responsibility, express remorse, and explain circumstances that might be considered favorably in sentencing.)

Ms. Wiener and her late mother sold works to the New York elite. They are credited with growing the market for Southeast Asian art, selling works to John D. Rockefeller III, Igor Stravinsky and Jacqueline Kennedy. Works from their gallery also appear at major museums nationally and internationally. In March 2015, Ms. Wiener reimbursed the National Gallery of Australia over a million dollars for a Buddha she had sold the institution in 2007, after it was discovered that the export of the item may have violated India’s laws.

National Gallery of Australia’s Seated Buddha (Photo Credit: Chasing Aphrodite)

In 2016, federal officials and the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office raided a number of galleries during Asia Week in New York. One of those galleries belonged to Ms. Weiner. The government seized objects from her gallery, arrested Ms. Wiener, and filed a felony complaint accusing the dealer of working with stolen objects for decades. Amineddoleh has spoken about the criminal case against Ms. Wiener in the past, including in 2017 when she was invited to speak during a conference for the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

The charges allege that Ms. Wiener obtained millions of dollars’ worth of stolen artifacts from international smugglers and sold them illegally — often through major auction houses. She is alleged to have laundered the illicit items by procuring restoration services to hide damage from illegal excavations, using straw purchases at auction houses to create sham provenances, and inventing and disseminating false histories to circumvent international patrimony laws that prohibit the exportation of looted antiquities. Upon her mother’s death, Ms. Wiener allegedly inherited hundreds of illicit items, discarded their records, and fabricated provenances. She then consigned hundreds of lots for sale at auction for millions of dollars.

In pleading guilty to these allegations, Ms. Weiner’s allocution statement reveals a great deal about the antiquities market. She characterizes that market as “a conspiracy of the willing,” saying that antiquities are often sold or consigned despite having suspect provenance — or no provenance at all. She also admits in detail to committing the common (and illegal) practice of fabricating provenance information to facilitate the sale or consignment of looted items. Despite claiming that her actions were motivated by her “passion” for the “great beauty” of historical objections, Ms. Weiner acknowledges that “it is not the right of any individual or institution to decide how to handle the cultural patrimony of another nation.”

Read more about the case in this article by Tom Mashberg.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Aug 23, 2021 |

In the latest entry of our firm’s ongoing Provenance Series, we discuss a new Polish law that will likely have serious negative implications for claimants seeking the return of property looted during the Second World War. In order to understand the context giving rise to this law, we delve into the country’s history of cultural heritage looting from 1939-1993, recent restitution cases, the provenance of the famous Czartoryski Collection, and the potential effects of Poland’s new law on lawsuits involving Nazi looted art and cultural heritage.

The Sacking of Poland’s Cultural Property During and After WWII

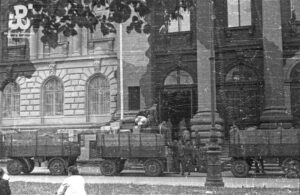

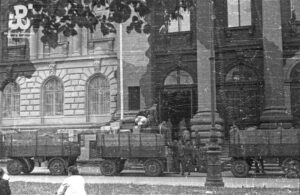

Germans looting the Zachęta Museum in Warsaw in the summer of 1944

It has been estimated that Poland suffered the staggering loss of 70% of its tangible cultural heritage during WWII at the hands of both the Nazis and the Soviet Union. This unprecedented loss amounts to approximately 500,000 cultural objects; many still unaccounted for, including masterpieces by Raphael, Albrecht Durer, Rembrandt, and other beloved Old Masters. The looting campaign was systematic, as the Nazis had a plan in place before invading Poland in 1939. Seizures were overseen by high-ranking officials, and then exacerbated by the Soviet Army and its subsequent decades-long occupation. Although the Nazis kept extensive documentation of their newly acquired spoils, much of the goods and records were lost during their evacuation of the Polish territories in 1944 and the ensuing turmoil. While the confiscations involved many Jewish families, not all property belonged to this minority; Christians, Roma, and political dissidents were also targeted. To illustrate, in 2007 a Polish count made a claim to a medieval cross worth $500,000 that was found in the trash in Austria, which had previously been forcibly removed from Poland. (The count is a member of the aristocratic Czartoryski family, whose collection is discussed below.)

Thus, restitution is a complex and sensitive subject given the horrific scale of suffering experienced by the Polish population both during and after WWII. A core factor complicating the return of cultural objects is the confiscation of such items by the Communist regime in the years after WWII, as Poland was not considered a sovereign nation with the capacity to enforce its national laws, particularly with respect to private property, until 1993. In some ways, the Communist mentality is still felt with regards to state-controlled property, including cultural objects. It is important to note that under Poland’s patrimony laws, dating as far back as 1918, cultural heritage is generally considered sovereign property. Therefore, recovery efforts are typically aimed at tracking down works for future custody and display in national museums and collections.

An additional obstacle is that class action suits to recover property from victims without heirs are regarded as incompatible with Polish law, as in the case of international Jewish organizations that claim property taken from Jews that have no living descendants. All these factors have resulted in Poland lagging behind other countries regarding the restitution of WWII-looted objects, despite some success stories (discussed below), and their cooperation with international organizations and law enforcement. Overall, the restitution process is expensive and time consuming for claimants, and the new law imposing a strict statute of limitations on claims will create further hindrances.

Polish Law and Difficulties in Returning Nazi Looted Cultural Heritage

Portrait of a Seated Woman by Thomas Couture (Photo courtesy of the German Lost Art Foundation)

Over the past decade, the Polish government has increased its efforts to recover looted cultural items from collections abroad. In 2011, the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage’s Division of Looted Art created a website to publicize its recovery efforts and assist in identifying missing works. The Division manages the only national cultural database of wartime losses and has gathered information on over 63,000 objects including paintings, coins, vehicles, sculpture, books, maps, toys, carpets, furniture, metalwork, and jewelry, among other items of artistic, historical, and sentimental value. The public can also access the list of recovered artworks online and use the Art Sherlock app to identify stolen or looted works. In 2012, it was announced that one of the most famous missing pieces, Raphael’s Portrait of a Young Man, had been supposedly found in a bank vault in an undisclosed location. However, it still has not entered the public eye. (One of our previous blog posts discusses the provenance of this fascinating work in more detail.) Moreover, this type of information gathering is time-consuming and requires both willing participation and accurate data. Collectors, dealers, and purchasers may be wary of publicly submitting such details if they come to realize that the provenances of works in their possession are problematic.

Another challenge for restitution claims is the applicable statute of limitation. Statutes of limitation are meant to ensure that a party is not prejudiced by another party’s undue delay or inaction in making a claim. In theory, this helps prevent false or outdated claims from commencing after proof has been lost or blurred by the passage of time. However, the strict application of statutes of limitations to Nazi looted property seems unjust and unfair, as a stolen item’s whereabouts are typically unknown for extended periods of time. If a private collector is in possession of such items, they may be hidden for years away from public view. Unless they are sold on the open market, for all intents and purposes, the works will have disappeared.

The Gurlitt Trove

A notorious example of this phenomenon is the “Gurlitt Trove,” containing nearly 1,400 works worth approximately $1.35 billion and which was discovered in 2012. Cornelius Gurlitt inherited the pieces from his father, an art dealer linked to the Nazis, and stashed them away for decades. After a chance cash check during a train journey, authorities became suspicious of tax evasion and raided Gurlitt’s apartment where they found a treasure trove or art. Gurlitt refused to return the works and argued that lawsuits would be blocked on statute of limitations grounds. Under German law, if a court found that Gurlitt was a good faith purchaser, he would have been entitled to keep the objects. Gurlitt ultimately reached an agreement with the Bavarian state prosecutor to return certain works to the heirs of their former owners. After his death in 2014, it was discovered that Gurlitt had bequeathed his collection to a Swiss museum. The German Lost Art Foundation, an organization founded by the German government, spent the next 6 years performing provenance research on the collection and identified several looted works that were then returned. These included Portrait of a Seated Woman by Thomas Couture (returned in January 2019 due in part to a tiny detail in the work) and Quai de Clichy by Paul Signac (returned in July 2019). Sadly, only a handful of works have been restituted to date because of the difficulty in obtaining accurate provenance information.

The Gurlitt controversy demonstrates that applying strict time limitations to claims may undermine the purpose of Holocaust-related restitution doctrines, which is to seek justice for those who were violently targeted by the Nazis. The Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art, drafted in 1998, encourage participating nations to return looted art to original owners or their heirs. Steps should be taken to achieve a just and fair solution, according to the circumstances of each specific case. While these principles are non-binding, they recognize that moral claims have a role to play in lawsuits concerning Nazi looted cultural property.

New Legislation in Poland

These issues have now been exacerbated by recent Polish legislation. Just this month, Polish President Andrzej Duda signed a law reducing the statute of limitations on all restitution cases to 30 years since the theft’s occurrence. In practical terms, this means that restitution of Nazi-looted items will become impossible since the thefts occurred nearly 80 years ago. Both the U.S. and Israeli governments, in addition to many cultural heritage experts, have denounced the decision. Although the law was criticized as “immoral” and a “disgrace,” the Polish government has defended its actions by saying that the new rules aim to end fraud and stop irregularity concerning property restitution, which the President terms “an era of legal chaos.” Last week, our founder was quoted in Artnet regarding the “overwhelming obstacles” victims in restitution cases face, including how proving legal title to stolen art decades later in a court of law is a tremendous challenge. The new law fails to account for these obstacles and the practical difficulties in overcoming them.

The Polish legislature could potentially carve out an exception for Holocaust looted property to prevent outstanding claims from being blocked, but the current law treats all property equally. The law has additionally been characterized as problematic for seemingly undermining Poland’s own efforts to recover cultural items at the national level. We discuss recent examples of returned Polish cultural property in the following two sections as a counterpoint to the new law.

A Spanish Museum Returns Flemish Paintings to Poland

Earlier this year, the Museum of Pontevedra in Spain announced that it would return two paintings by Flemish artist Dieric Bouts to Poland. The late 15th Century works depict the Virgin of Sorrows and Jesus Christ in his Ecce Homo aspect. They were purchased from one of the museum’s patrons who likely acquired them from a Spanish dealer in the 1970s. The paintings were displayed openly for years, without any suspicion regarding their origins. Then, in late 2019 the museum was alerted by Polish authorities that the paintings closely resembled ones looted by the Nazis that were destined as a gift for Hitler. It is unclear when or how the paintings arrived in Spain, but it is certain that they were taken by the Nazis from the medieval Goluchów Castle in Poznan since they appeared in a German inventory of the country’s most valuable cultural items during WWII. After receiving notification from Poland, the museum engaged a team of experts to examine the works, which were found to match the missing items.

Earlier this year, the Museum of Pontevedra in Spain announced that it would return two paintings by Flemish artist Dieric Bouts to Poland. The late 15th Century works depict the Virgin of Sorrows and Jesus Christ in his Ecce Homo aspect. They were purchased from one of the museum’s patrons who likely acquired them from a Spanish dealer in the 1970s. The paintings were displayed openly for years, without any suspicion regarding their origins. Then, in late 2019 the museum was alerted by Polish authorities that the paintings closely resembled ones looted by the Nazis that were destined as a gift for Hitler. It is unclear when or how the paintings arrived in Spain, but it is certain that they were taken by the Nazis from the medieval Goluchów Castle in Poznan since they appeared in a German inventory of the country’s most valuable cultural items during WWII. After receiving notification from Poland, the museum engaged a team of experts to examine the works, which were found to match the missing items.

The museum indicated it would return the works to Poland. Polish authorities commended the museum’s willingness to do so voluntarily, even though it had acquired them in good faith (as such, the museum had a legal claim of ownership under Spanish law). The case was cited as an example of integrity and transparency. César Mosquera, vice president of the Pontevedra city council, announced that they were proud to return these works in light of their dark origins.

The Provenance of the Czartoryski Collection

Lady with an Ermine, Leonardo da Vinci

The famed Czartoryski Collection has reached mythical proportions in Poland, not only due to the breadth of its works, but also the family’s travails. This aristocratic family is closely tied to the political and cultural history of the Polish state. In 1796, Princess Izabella Czartoryska opened the first Czartoryski Museum at her residence in Pulawy, showcasing her antiques and paintings. Leonardo da Vinci’s Lady with an Ermine and Raphael’s Portrait of a Young Man formed part of this esteemed group. During the Russian occupation of Poland in 1830, the family fled and ultimately resettled in Paris. While the Raphael painting was lost, the Princess saved the Leonardo by sending it 100 miles south to the Czartoryski palace at Sieniawa, before it joined the family in Paris. The Czartoryskis returned to Poland and opened another two museums by 1878, one in Warsaw and one in Goluchów Castle. The Castle collection consisted of over 5,000 decorative art objects and several hundred valuable paintings. In 1939, as the Nazis approached Poland, the widow of Prince Adam Ludwik Czartoryski removed the most valuable works from the castle, concealed them in 18 boxes, and hid them behind a wall in the wine cellar. However, Nazi officials coerced her into revealing the objects’ location. The Nazis confiscated the items and moved them to the National Museum of Warsaw in 1941, where they were inventoried and photographed. Some of the pieces were taken to Austria, while others were pillaged by deserters and refugees at the end of the war. Lady with an Ermine was fortunately returned in 1946, after its discovery by Allied soldiers (the Monuments Men) in Germany. Unfortunately, the collection was then under the Communists’ control until the fall of the Soviet Union. The family has spent decades attempting to track down their treasures. Prince Adam Karol Czartoryski, born and raised in Spain, has made it his life’s mission to recover what was stolen and established the Princes Czartoryski Foundation in 1991 for this purpose.

In 2016, the Prince signed an agreement with the Polish government selling the collection of 86,000 artworks and 250,000 historic manuscripts to the state for €100 million (a fraction of its total value). It was considered a tremendous bargain for Poland, and the sale was hailed as a donation. The agreement stipulated that the National Museum in Krakow would control the buildings owned by the Czartoryski family and used for the display of the works, and the collection was made publicly available in 2019 after extensive renovations. Despite some controversy over the nature of the purchase, the collection now attracts visitors from all over the world. The government also signed a separate agreement with the Czartoryskis for the acquisition of Goluchów Castle and its art collection. However, the family retains the right to make claims for the return of still-missing looted cultural objects, estimated at 800 pieces. This means that cases involving the Czartoryski collection could arise in the future, whether in Poland or abroad.

The Future of Polish Restitution and its Effects in the U.S.

Warsaw Castle (photo courtesy of Claudia Quinones)

Poland has received criticism for lacking viable procedures to process restitution claims from Holocaust victims, within the country and from abroad. It has also failed to uphold the Washington Principles despite benefiting from restitution laws of other nations, including the U.S. This, combined with the new law’s restrictive statute of limitations, may prompt claimants to file lawsuits in more forgiving jurisdictions, such as the U.S. (however, jurisdictional challenges remain for claimants to prove proper jurisdiction within the U.S.). Restitutions of Nazi-looted art involving foreign claimants have become prominent in the U.S., including the well-known cases of the Altmann family’s claim to Klimt’s Lady in Gold and the ongoing Guelph Treasure litigation. The statute of limitations for theft in general may be tolled under the Demand and Refusal Rule or the Discovery Rule. The Demand and Refusal Rule, which only applies in New York, holds that the statute of limitations begins to run when the original owner demands restitution, and the current possessor refuses to return the object. The Discovery Rule deems that time begins to run when an owner knows or reasonably should know the location of the object.

At the federal level, U.S. Congress passed the Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery Act of 2016 (HEAR Act) providing a 6-year statute of limitations for Nazi looted cultural property that does not begin to run until the object in question is actually discovered and knowledge of it is obtained. This is more favorable for claimants, allowing them greater opportunity to make plans of action for restitution. Notably, the Act has the potential for cases that were previously barred under statute of limitations rules to be “resuscitated” in special circumstances. However, while the Act replaces state and federal statutes of limitations for art recovery claims with a uniform period to make a claim, this is only temporary (until 2026).

The HEAR Act also allows claimants to side-step the good faith purchaser loophole present in many countries, including Poland. The U.S. follows the nemo dat rule, holding that a thief cannot transfer good title to stolen property. This fault in title continues to taint subsequent purchasers. If claimants have a connection with the U.S., they may be able to file a suit for the restitution of looted cultural property there, even if the object is located in another state such as Poland. Likewise, Poland could appear in a U.S. court to request repatriation if there is sufficient nexus, or the nation may request assistance from U.S. authorities. For example, in 2014, the FBI was contacted by Poland and tracked down 75 paintings by a Polish resistance fighter who moved to San Francisco after escaping a concentration camp. Although Poland’s law may affect domestic claims, the door remains open for international cooperation, which may have a more favorable outcome.

The effects from the Polish law remain to be seen, but there is no stemming the tide of restitution for Nazi looted cultural heritage. Although countries have experienced setbacks with restitution claims, cultural heritage attorneys will continue to seek justice in the face of procedural and legal hurdles.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jun 14, 2021 |

Virtual restoration of the Old Summer Palace during the Qing Dynasty, 1644-1911. (Copyright: Asianewsphoto)

Over two thousand years ago, the Jade Emperor, Supreme God of the Heavens in Taoism mythology, launched what is now known as the Great Race. The invitation was extended to every animal species in the Empire but, because of prior engagements or travel restrictions, only twelve (the Pig, Rooster, Sheep, Horse, Dog, Monkey, Snake, Rabbit, Dragon, Tiger, Rat, and Ox) attended the event. In gratitude, the Jade Emperor promised each participant it would be attributed a zodiac year and two hours of the day. The first to reach the finish line would become the first zodiac sign and the first two hours of the day, and so on. The race crossed all terrains, with its climax being a river crossing. Rat, the group’s smallest member, feared for its life; until it spied Ox. The bovine was known to have poor vision so Rat offered to direct it through the river by riding on its back. Ox agreed and they began the final leg of the journey. Yet once the pair grew close to the opposite bank, Rat jumped off Ox’s head and won the race. To this day, Rat remains the first sign in the Chinese zodiac and it symbolizes hours 11:00pm to 1:00am.

Under the Qing dynasty in the 18th century, Emperor Qianlong commissioned the creation of the Old Summer Palace in Beijing. Reigning over 715 acres of utopian hills and gardens, the palace hosted the empire’s formal and recreational stays. Within this land, hidden in the Garden of Eternal Spring, was the Haiyantang water-clock fountain. Giuseppe Castiglione, an Italian painter, designed the fountain to include twelve bronze heads in the shapes of the zodiac animals, which sprouted water at the hours to which the creatures were assigned in the Great Race myth. Water speared out of Rat’s mouth at midnight and Rabbit rose with the sun from 5:00 to 7:00am.

In 1856, the British declared the Second Opium War against the Qing government. The French joined soon after. Four years into the war, British High Commissioner to China, James Bruce, the Eight Earl of Elgin entered the picture. The son of the Thomas Bruce (known for removing from marble frieze from the Parthenon), James Bruce ordered the burning and looting of the Old Summer Palace. Like his father, James has faced the ire of history due to his destruction and theft of a nation’s heritage. He knew that amongst the Chinese Palace’s treasures, the fountain’s bronze heads were no small catch. The French and British soldiers likely traded some of the loot amongst themselves. We now know most of the bronze heads were sent to Europe.

In 1856, the British declared the Second Opium War against the Qing government. The French joined soon after. Four years into the war, British High Commissioner to China, James Bruce, the Eight Earl of Elgin entered the picture. The son of the Thomas Bruce (known for removing from marble frieze from the Parthenon), James Bruce ordered the burning and looting of the Old Summer Palace. Like his father, James has faced the ire of history due to his destruction and theft of a nation’s heritage. He knew that amongst the Chinese Palace’s treasures, the fountain’s bronze heads were no small catch. The French and British soldiers likely traded some of the loot amongst themselves. We now know most of the bronze heads were sent to Europe.

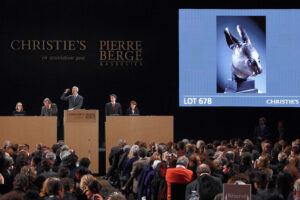

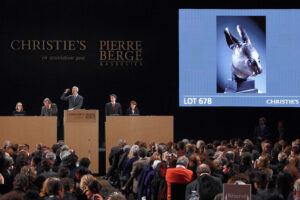

World-renowned French fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent and his partner Pierre Bergé spent years acquiring an enviable art collection. From their first acquisition of a wooden bird sculpture, Oiseau Sénoufo, originating from Côte d’Ivoire in 1960, animals became a central theme in their collection. When Saint Laurent died in 2008, Bergé auctioned off a large part of their collection with Christie’s Paris the following year. Up for auction were the rat and rabbit heads. They may have gone unnoticed, but the Republic of China had had its eyes out for the bronzes for nearly a decade. Back in 2000 the tiger, the monkey, and the ox were the first zodiac heads to reappear on the public art market. At the time, they were featured in Christie’s and Sotheby’s auction catalogues for their upcoming sales. The Chinese State Bureau of Cultural Relics promptly wrote to the auction houses demanding the withdrawal of the bronze heads from the sales. The Chinese government did not formulate an official restitution request because international conventions were viewed as inapplicable to lootings that occurred over 140 years ago. As a result, the auction houses rejected the State’s request. In an unexpected turn of events, however, China Poly Group Corp. Ltd.placed its live bids on all three heads, and won them for a total of $4 million dollars. The sculptures were placed in this state-owned corporation’s Poly Art Museum in Beijing, which is dedicated to Chinese heritage. Three years later, the same museum acquired the pig head from Chinese billionaire Stanley Ho, who had bought it from a New York collector. Finally, in 2007, Ho purchased the horse head from Sotheby’s Hong Kong for $8.9 million dollars.

Jackie Chan wrote, directed, and starred in a film about the stolen zodiac bronzes.

It came as no surprise when Christie’s Paris received a letter from the Chinese government in February 2009 asking that the rat and rabbit heads be removed from the Yves Saint Laurent-Bergé sale. It was also to be expected that the auction house would refuse. In protest, the “Association pour la protection de l’art chinois en Europe” (the Foundation for the protection of Chinese art in Europe) along with eighty other Chinese lawyers, filed a complaint with the “juge des référés” whose role in France is to deliver temporary restraining orders in time-sensitive situations. Two days before auction, the tribunal rejected the foundation’s request to enjoin the sale.

THE PROVENANCE: In its press release on the three-day Saint Laurent estate sale, Christie’s described the zodiac bronze heads as the “two main pieces” amongst the works for sale. The sculptures’ provenance revealed that Saint Laurent had acquired them from the Kugel brothers at their famous Galerie Kugel in Paris. The Kugels bought the bronze heads from the marquis de Pomereu in 1986 who had attained them from the Spanish painter José María Sert.

On the closing day of the sale, February 25, 2009, the rat and rabbit bronzes sold for the equivalent of nearly $40 million. A few days later, the winning bidder refused to pay for them. Cai Mingchao, a self-described Chinese patriot, explained his act was a national duty. “This money,” he claimed, “should not be paid.” The Chinese government publicly supported Mingchao’s fraud and, in addition, placed tighter trade restrictions on Christie’s art trades, ordering local law enforcement officials to report any artifact that might have been looted and trafficked. Following Mingchao’s refusal to pay for the sculptures, Pierre Bergé eventually sold the lots to French billionaire François Pinault, the owner of Christie’s.

Rabbit bronze for auction at Christie’s (Copyright: Agence France-Presse)

However, the story was not over. In 2013, Pinault announced that the rat and rabbit heads would return to Beijing. But the animals’ race home came at a price. Curiously, this donation occurred only a few days after Christie’s was granted a license to conduct business on mainland China. Most recently, in December 2020, China’s National Cultural Heritage Administration launched the return of the horse head. The Summer Palace was restored in 1886, twenty-six years after its destruction. However, the dragon, dog, sheep, snake, and rooster have yet to reach to finish line and return home.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Feb 28, 2021 |

It is a bitter truth that women, who are so often depicted, admired and romanticized through art, have had to overcome herculean obstacles to participate in its creation. In honor of Women’s History Month, this entry in our Provenance Series examines the work of the Old Masters’ female counterparts – the Old Mistresses – and their contemporary successors.

Rediscovery of Female Artists

Plautilla Nelli’s Last Supper (prior to restoration)

Renaissance and Baroque works by women have deservedly entered the public consciousness in recent years. In 2019, a depiction of the Last Supper by nun Plautilla Nelli was installed in the Santa Maria Novella Museum in Florence, after a painstaking 4-year restoration by the Advancing Women Artists Foundation (AWA). The project was made possible through the AWA’s “adopt an apostle” crowdsourcing program: private financiers were allowed to “adopt” one of the life-sized disciples at $10,000 each (ever-unpopular Judas was instead funded by 10 backers at only $1,000 each). The oil painting, measuring 21 feet across, is one of the largest Renaissance works by a female artist still in existence. It is also the only work created by a woman during the Renaissance depicting the Last Supper.

The Provenance and Restoration of Plautilla Nelli’s The Last Supper

Santa Maria Novella in Florence, Italy (Courtesy of CAHKT/iStock.com)

The Last Supper was likely created for the benefit of Plautilla’s own convent, the convent of Santa Caterina di Cafaggio in Florence, where it hung in the refectory (dining hall) until the Napoleonic suppression in the 19th century, when the convent was dissolved. It was thereafter acquired by the Florentine Monastery of Santa Maria Novella in 1817. Again, it was housed in the refectory until being moved to a new location in 1865. Scholar Giovanna Pierattini reports it was moved to storage in 1911, where it remained until 1939. It then underwent significant restoration, and returned to the refectory. It would remain on display there for almost forty years, surviving the historic flood of the Arno in 1966 with little damage. The work was next taken down in 1982, when the refectory was reclassified as the Santa Maria Novella Museum, and transferred to the friars’ private rooms. This is how the monumental work, which remained out of the public eye for centuries, is now visible to the public for the first time in 450 years.

Rossella Lari, the restoration’s head conservator remarks, “We restored the canvas and, while doing so, rediscovered Nelli’s story and her personality. She had powerful brushstrokes and loaded her brushes with paint.” The painting features emotionally charged expressions, emphatic body language, and exquisite details, such as the inclusion of customary Tuscan cuisine (roasted lamb and fava beans).

Plautilla’s use of color and composition is even more impressive when one considers that women were barred from attending art schools and studying the male nude; instead, they were forced to rely on printed manuals and the works of other artists. Plautilla was not only a self-taught artist, but she also ran an all-woman workshop in her convent and received the ultimate praise for an Italian Renaissance painter: inclusion in Giorgio Vasari’s seminal book Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects. Notably, in Plautilla’s time the convent was managed by Dominican friars previously under the leadership of fire-and-brimstone preacher Girolamo Savonarola. The nuns were encouraged to paint devotional pictures in order to ward off sloth. Undeterred, “Plautilla knew what she wanted and had control enough of her craft to achieve it,” says Lari. The Last Supper is signed “Sister Plautilla – Orate pro pictora” (“pray for the paintress”). Plautilla thus confirmed her role as an artist while acknowledging her gender, understanding that the two were not mutually exclusive. Although only a handful of the works survive today, Plautilla and her disciples created dozens of large-scale paintings, wood lunettes, book illustrations, and drawings with great focus, determination, and discipline. She is considered the first true woman artist in Florence and in her heyday, “There were so many of her paintings in the houses of gentlemen in Florence, it would be tedious to mention them all.” Since AWA’s conservation work was initiated, the number of works attributed to Plautilla has risen from three to twenty, meaning that other undiscovered masterpieces could be lying in wait.

Female-Led Museum Exhibitions

Last year, the Prado Museum in Madrid hosted an exhibition featuring two overlooked Baroque painters, Sofonisba Anguissola and Lavinia Fontana, in an exhibition entitled “A Tale of Two Women Painters.” Meanwhile, the National Gallery in London hosted a show dedicated to Artemisia Gentileschi. Notably, Sofonisba, Lavinia and Artemisia all achieved fame and renown during their lifetimes, including royal commissions, only to be eclipsed for centuries after their deaths. Sofonisba was particularly sought after for her ability to capture the expressiveness of children and adolescents in intimate portraits, while Lavinia’s commissions displayed a more formal Mannerist style. Artemisia, the subject of the National Gallery’s first major solo show dedicated to the artist, is recognized as much for the strength of her figures in chiaroscuro as for her life story involving sexual assault and trial by torture. Despite considerable difficulties, Artemisia was able to succeed in a male-dominated field and created over 60 works, most of which feature women in positions of power. Artemisia is now hailed as one of the most important painters of her generation and an established Old Mistress in her own right.

Female Artists at Auction

Artemisia Gentileschi’s Lucretia (ca. 1630-1640)

Despite their long slumber in the annals of history, these artists are not only receiving attention in museums, but in auctions as well. In 2019, a painting by Artemisia depicting Roman noblewoman Lucretia shattered records when it sold for more than six times its estimated price at Artcurial in Paris. While estimates originally placed the work at $770,000 to $1 million, the painting was ultimately acquired by a private collector for $6.1 million. Lucretia was discovered in a private art collection in Lyon after remaining unrecognized for 40 years. It was in an “exceptional” state of conservation according to Eric Turquin, an art expert specializing in Old Master paintings previously at Sotheby’s.

The earlier record for one of Artemisia’s works had been set in 2017, when a painting depicting Saint Catherine sold for $3.6 million. That painting, a self-portrait of the artist, was then acquired by the National Gallery in London for $4.7 million in 2018. This was the first painting by a female artist acquired by the National Gallery since 1991, and the 21st such item in its entire collection, which encompasses thousands of objects. Saint Catherine had been owned by a French family for decades, but its authorship was obscured prior to its rediscovery and sale by auctioneer Christophe Joron-Derem. The painting was acquired by the Boudeville family in the 1930s, but the exact circumstances of this acquisition and the painting’s prior whereabouts were unclear. At the time of the National Gallery’s purchase, museum trustees raised concerns that the work might have been looted during World War II, although there is no firm evidence to support this suspicion. Despite the gaps in the works’ provenance, it was ultimately determined that the painting had been with the family for several generations and Saint Catherine was welcomed to her new home in London.

Recent Attributions

Artemisia Gentileschi, David and Goliath (Courtesy of Simon Gillespie Studio)

More recently, a painting of David and Goliath was attributed to Artemisia after a conservation studio in London removed layers of dirt, varnish and overpainting to reveal her signature on David’s sword. While the work’s attribution occurred too late for inclusion in the National Gallery exhibition, the owner is apparently delighted to discover the work’s true author and is keen to loan it to an art institution so the public can enjoy the work. This painting was originally acquired at auction for $113,000 and may have been owned by King Charles I – quite an esteemed pedigree and sure to raise its value by a considerable amount.

In contrast to Artemisia’s ascendance, a painting once attributed to her father Orazio Gentileschi is now embroiled in controversy. That painting, which also depicts David and Goliath and described as “stunning” by the Artemisia show curator, has links to notorious French dealer Giuliano Ruffini. Ruffini is the subject of an arrest warrant due to his connection with a high-profile Old Master forgery ring operating in Europe. It is believed that the forgery ring, uncovered in 2016, garnered $255 million in sales, including works represented as being by Lucas Cranach the Elder and Parmigianino. Although these paintings were widely accepted as genuine masterpieces and fooled leading specialists, they did not have verifiable provenances. The paintings were said to belong to private collector André Borie, although that was not the case and Sotheby’s was forced to refund money to buyers once the fraud came to light. The Gentileschi in question had been “discovered” in 2012 and sold to a private collector, who loaned it to the National Gallery in London. At that time, the painting was praised for its “remarkable” lapis lazuli background, but the museum did not conduct a technical analysis before displaying the piece. Despite several warning signs – the painting’s recent entrance into the art market, its unusual material, its similarity to another Gentileschi painting held in Berlin, and the lack of published provenance – the museum stated that there were “no obvious reasons to doubt” the painting’s attribution.

The forgotten nature of some female artists demonstrates that their talents are not rare, but rather that they lack the opportunities and publicity that male artists often take for granted. Once their talent is amplified, female artists are capable of great things. This pattern continues today.

The Modern Struggles of Female Artists

As famous female artists lost to history capture the public eye, they are joined by female contemporaries who share a similar struggle against underrepresentation. Women’s contribution to modern and contemporary art is often exemplified by those with ties to established male artists: Mary Cassatt (who achieved recognition as an Impressionist in Paris through her relationship with Edgar Degas); Georgia O’Keeffe (who entered the public eye via her relationship to Alfred Stieglitz); and Frida Kahlo (introduced to the art world by her husband, Diego Rivera). This truncated view ignores the vast amount of creative output generated by women, and reinforces the notion that recognition must be made through a male lens, a view prevalent during Artemisia’s time. It is worth noting that Artemisia’s father Orazio Gentileschi was her teacher and facilitator in the Baroque art market. In fact, this attitude has denied countless female artists of their deserving places in the canon of art history. It has even enabled surreptitious artists to take credit for works by others.

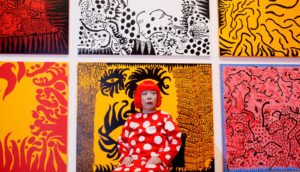

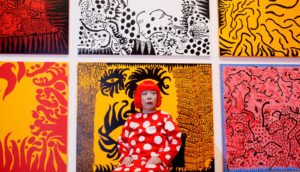

Yayoi Kusama (Courtesy: Kirsty Wigglesworth AP/Shutterstock.com)

Today, Yayoi Kusama is a household name. The world’s top-selling female artist, she is renowned for her peculiar polka-dotted paintings and sculptures, which command long lines at preeminent art institutions across the globe. Like many famous contemporary artists from the last century, she is strongly associated with a unique personal style, and recognized by her bright-red wig. Despite her phenomenal success, her position in the pantheon of notable contemporary artists was anything but assured. Born in the rural town of Matsumoto, Japan in 1929, Kusama was discouraged from pursuing a career; rather, she was encouraged to marry and start a family. Frustrated by the constant efforts to suppress her artistic aspirations, she wrote to the already famous Frida Kahlo for advice. Kahlo warned that she would not find an easy career in the US, but nevertheless urged Kusama to make the trip and present her work to as many interested parties as possible.

Unsurprisingly, Kahlo’s advice was accurate. After traveling to New York, Kusama’s early work received praise from notable artists Donald Judd and Frank Stella, but it failed to achieve commercial success. Her work also attracted the attention of other renowned artists, who were able to channel ‘inspiration’ from Kusama’s work right back into the male-dominated New York art market. Sculptor Claes Oldenburg followed a fabric phallic couch created by Kusama with his own soft sculpture, receiving world acclaim. Andy Warhol repurposed her idea of repetitious use of the same image in a single exhibit for his Cow Wallpaper. Most blatantly, after exhibiting the world’s first mirrored room at the Castellane Gallery, Lucas Samaras exhibited his own mirrored exhibition at the Pace Gallery only months later. Needless to say, these artists did not credit Kusama for her work and originality. This ultimately caused a despondent Kusama to abandon New York and return to Japan.

Kusama spent the next several decades largely in obscurity. The frustrations in her career resulted in multiple suicide attempts and long-term hospitalizations. However, Kusama always found a way to channel this energy back into her art, and she continued to create art in various formats as a way to heal. It was not until a 1989 retrospective of her work in New York and an exhibition at the 1993 Venice Biennale that the world truly tok notice of her work. This global reintroduction was enough to galvanize interest in her artistic creation, leading to the success she enjoys today. While it may seem just that such a talented artist would eventually receive recognition for her work, this is not always a given and Kusama’s near erasure from the art world should not be discounted.

The Gendered Art Market Divide

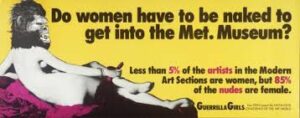

In today’s art market, artists, collectors, dealers, and museums are making a concerted effort to fight this type of erasure. Kusama stands as a beacon to others, demonstrating that female artists can reach the pinnacle of their profession. However, it remains an arduous career path for many. Statistical analysis confirms that female artists are underpaid and underrepresented in both the primary and secondary art markets. For example, compare the highest price paid for a work by a living artist by gender: Jeff Koons’ Rabbit sold for $91.1 million in 2019; while Jenny Saville’s Propped sold for $12.5 million that same year, a mere 14% of the Koons’ price. Some of this disparity can be explained by the difference between men and women’s treatment in the workplace generally, but the art world is also subject to a number of particularities. Attributed to a host of causes, perhaps none is more prominent than women’s almost total exclusion from studio art until the 1870s. The art world has existed in this environment for so long that its institutions and relationships now mechanically reinforce the disparity between genders: women are less likely to receive recognition and training, and buyers are less interested in art created by females. The interest in female-made art is also disproportionality concentrated on its biggest names; the top five best-selling women in art held 40% of the market for works by women auctioned between 2008 and 2019. It has become a self-sustaining cycle that can only be broken through deliberate and effective action.

Initiatives Supporting Female Artists

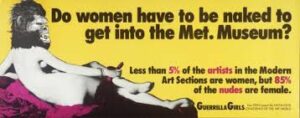

Artists and galleries have been working to shine a light on the current landscape of inequality in the market. Groups like the Guerilla Girls have used their cultural status and notoriety to vocalize issues regarding sexism, racism, and other types of discrimination still rampant today. This type of radical-meets-reformer message resonates with a newer generation that is more vocal about addressing discrimination, and frustrated by the seemingly lackluster efforts to minimize their impact on society. In honor of Women’s History Month, several galleries have announced shows dedicated to addressing some of these issues. The Equity Gallery is presenting “FemiNest,” a collection of works by female artists centered around the literal and metaphorical ideas conjured by the idea of a “nest.” The show explores in sculpture, textiles, painting and other media the new spaces that have opened for women in recent decades and their practical and spiritual impact for women. The Brooklyn Museum has announced a retrospective of Marilyn Minter’s work titled “Pretty/Dirty” aimed at challenging traditional notions of feminine beauty. Featuring more than three decades of work, the show will track Minter’s progress throughout the 1970s, 80s, and 90s. The show is also part of a larger series of ten exhibitions by the Brooklyn Museum dedicated to the subject: “A Year of Yes: Reimagining Feminism at the Brooklyn Museum.” Lastly, the Zimmerli Art Museum will feature an exhibition of works by the Guerilla Girls and other female artists who have worked to depict women’s unequal treatment in the art world, “Guerrilla (And Other) Girls: Art/Activism/Attitude.” (For more information about these shows and others addressing similar issues, see here.)

Although artists and art institutions have just begun the work of winding back centuries of discrimination, there is evidence that their work is already affecting the market. The percentage of female-generated artwork in the secondary market is increasing from year to year; from 2008 to 2018, the market more than doubled from $230 million to $595 million. Similarly, representation of women at major art shows is steadily, if inconsistently, increasing as well. This subtle shift in the market has been attributed at least in part to a new class of art purchaser: independently wealthy women, whose capital is self-made rather than inherited or shared via marriage. This novel source of demand is less sensitive to the traditional pressures of the market and is helping to fuel demand for works by female artists. Women’s History Month is an opportunity to reflect on the tremendous progress made by remarkable individuals in the art world, and to also contemplate the ripe opportunities that still lie ahead.

At Amineddoleh & Associates LLC, we are proud to have an inclusive team that represent a diverse roster of clients, including female artists, dealers, collectors, and businesswomen.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jan 27, 2021 |

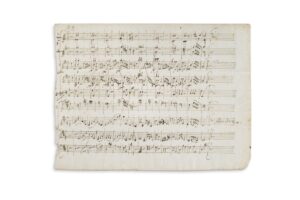

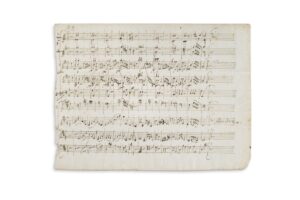

Mozart’s manuscript that sold at Sotheby’s for $413,000 in 2019.

Today we celebrate the 265th anniversary of the birth of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart with a special entry in our provenance series. Centuries after his birth, Mozart continues to dazzle the public imagination through reinterpretations of his work, including The Magic Flute by Julie Taymor, Academy Award-winning film Amadeus, and the Amazon Prime series Mozart in the Jungle. As the works of a musical prodigy and globally-recognized composer, Mozart’s manuscripts are highly prized by collectors. One such piece, an original score with two minuets dating from 1772, sold for $413,000 (€372,500) at auction in 2019. Notably, Mozart was only 16-years-old when he created the works. The first versions of Mozart’s scores are significant because, unlike Beethoven, the young composer did not make major revisions to his drafts. This means that there are fewer copies in existence, making them both rare and valuable. Indeed, the final hammer price for this piece exceeded the projected value by nearly double.

The minuet score has an esteemed provenance; it was originally kept by Mozart’s sister Nannerl (who was an accomplished musician and composer herself), and ultimately entered the collection of Austrian writer Stefan Zweig. Upon Zweig’s death in 1986, his collection of manuscripts, including Mozart’s handwritten catalogue of works, was donated to the British Museum. The score was later acquired by Swiss bibliophile Jean-François Chaponniere, making it the only copy of an autograph composition by Mozart in private hands. Moreover, this is the only surviving copy of this particular composition in manuscript form. The other manuscripts in this minuet series are currently held by the US Library of Congress and the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, Austria.

However, Mozart’s manuscripts were already setting records prior to the 2019 auction. In 1987, a private collector paid $4.4 million for a 508-page compendium of Mozart’s scores, which was the highest amount paid for a post-medieval manuscript at the time. To compare, the previous record for a musical manuscript was $544,500 for an incomplete copy of Igor Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring” in 1982. The 1987 record was later surpassed in 2016, when a handwritten score of Gustav Mahler’s Second Symphony was auctioned for $5.6 million. Although the value of classical music compositions has risen sharply in the past few decades, this phenomenon is not free from controversy. A score attributed to Beethoven failed to sell at Sotheby’s when scholars questioned the authenticity of the work. This demonstrates the importance of establishing provenance for all types of collectible items, even those tied to musical geniuses. Fortunately, the minuet score posed no such problems, making it a true prize.

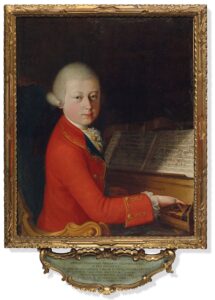

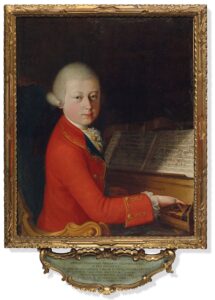

Sold for $4.4 million, the portrait of the teenage Mozart has an alluring provenance.

But private collectors’ interest in Mozart is not limited to musical manuscripts; a rare portrait of the composer as a teenager fetched €4,031,500 at auction soon after the minuet score was sold in 2019. The painting has an impeccable provenance, as it was referenced in a letter from Mozart’s father Leopold to his wife Maria Anna, dated January 1770. In 1769, Mozart had toured Italy with his father. At the age of 13, he was already a celebrity recognized for his remarkable musical talent. During Mozart’s stay in Verona, a passionate music lover commissioned a portrait of the prodigy. This is one of only five confirmed portraits of the composer painted during his short life.

What is unusual for this painting, aside from its glimpse of the composer as a young man, is the thorough documentation of the circumstances leading to its creation. Pietro Lugiati, Receiver-General for the Venetian Republic and member of a powerful Veronese family, commissioned the work while hosting Mozart and his father in Italy. The portrait depicts the teenager in a powdered wig and red frock before a Renaissance harpsichord in Lugiati’s music room. By all accounts, Lugiati was so in awe of the young Mozart he described the child as a “miracle of nature in music” in a letter to the composer’s mother and essentially detained the Mozarts for two days, until the portrait was completed.

Curiously, despite the references to the painting in contemporaneous documents, the artist remains unconfirmed. While it is likely that the painter was leading Veronese artist Giambettino Cignaroli (he referenced Mozart’s visit to his studio), an alternative attribution is Saverio della Rosa, Cignaroli’s nephew. The painting could also have been a collaboration between the two artists. Although firm attribution remains elusive, the painting was an immediate success – one of the world’s oldest newspapers, La Gazzetta di Mantova, praised the work a mere five days after it was finished – a fitting tribute to a great musician.

The Mozarteum (the house where Mozart was born) in Salzburg, Austria is currently closed due to COVID. And it is not possible for most people to purchase original manuscripts of the musical prodigy, but we can celebrate the musical genius’ birthday by listening to one of over 600 musical compositions he wrote. Happy birthday Wolfgang!

Earlier this year, the Museum of Pontevedra in Spain

Earlier this year, the Museum of Pontevedra in Spain

In 1856, the British declared the Second Opium War against the Qing government. The French joined soon after. Four years into the war, British High Commissioner to China, James Bruce, the Eight Earl of Elgin entered the picture. The son of the Thomas Bruce (known for removing from marble frieze from the Parthenon), James Bruce ordered the burning and looting of the Old Summer Palace. Like his father, James has faced the ire of history due to his destruction and theft of a nation’s heritage. He knew that amongst the Chinese Palace’s treasures, the fountain’s bronze heads were no small catch. The French and British soldiers likely traded some of the loot amongst themselves. We now know most of the bronze heads were sent to Europe.

In 1856, the British declared the Second Opium War against the Qing government. The French joined soon after. Four years into the war, British High Commissioner to China, James Bruce, the Eight Earl of Elgin entered the picture. The son of the Thomas Bruce (known for removing from marble frieze from the Parthenon), James Bruce ordered the burning and looting of the Old Summer Palace. Like his father, James has faced the ire of history due to his destruction and theft of a nation’s heritage. He knew that amongst the Chinese Palace’s treasures, the fountain’s bronze heads were no small catch. The French and British soldiers likely traded some of the loot amongst themselves. We now know most of the bronze heads were sent to Europe.