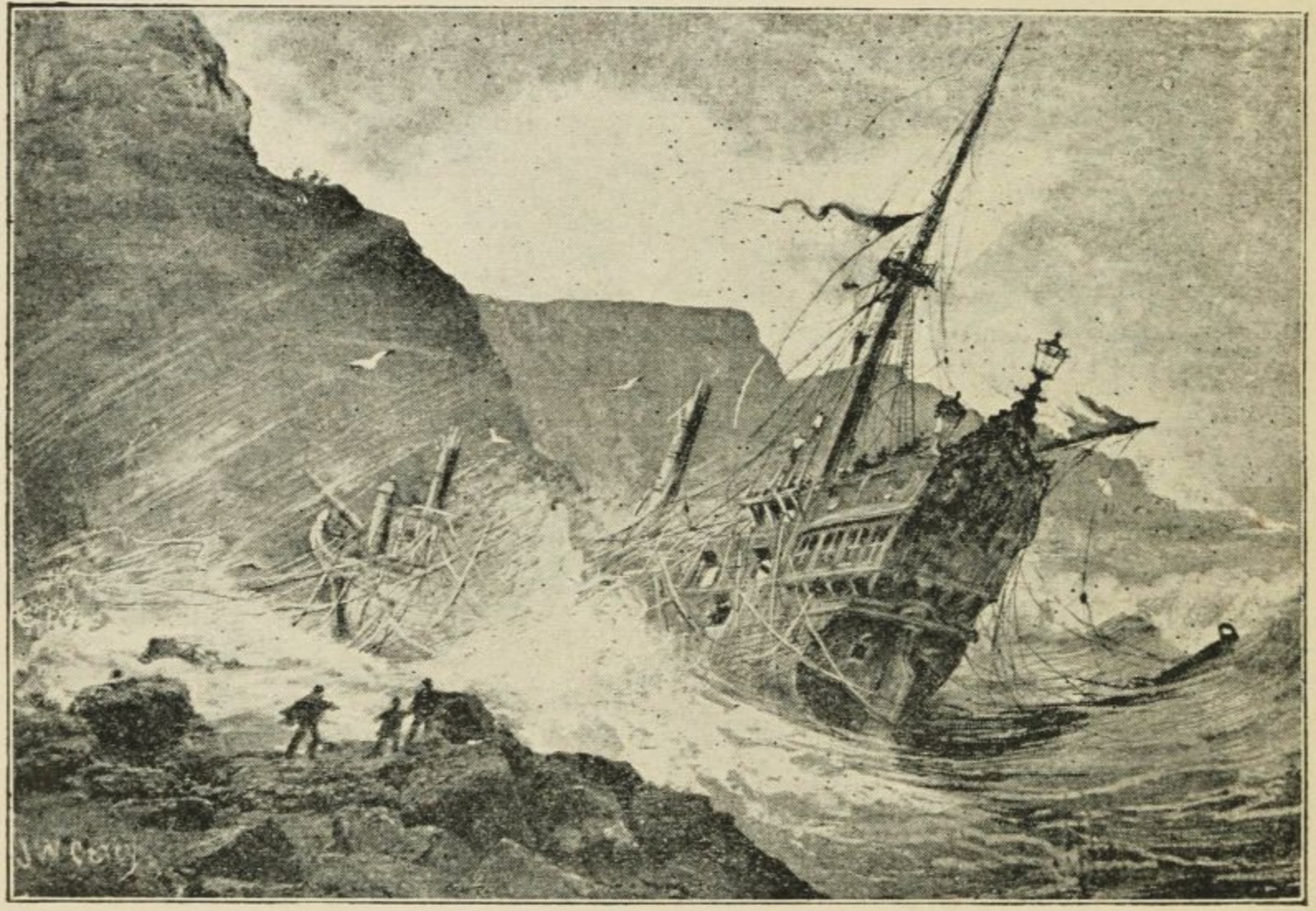

Do you remember The Goonies, the 1985 Spielberg film about a shipwreck that made amateur treasure-hunters out of an entire generation? It turns out that the film may have been inspired by a real-life shipwreck. In 1693, the Spanish galleon Santo Cristo de Burgos mysteriously disappeared while en route to Mexico from the Philippines.

Historians have long searched for answers about the ship’s tragic fate, and they may have recently found them washed ashore on the Oregon coast. Large pieces of timber discovered by beachcombers sparked an incredible recovery effort, which has produced further evidence that Astoria, Oregon is where the Santo Cristo de Burgos met its end.

Historians have long searched for answers about the ship’s tragic fate, and they may have recently found them washed ashore on the Oregon coast. Large pieces of timber discovered by beachcombers sparked an incredible recovery effort, which has produced further evidence that Astoria, Oregon is where the Santo Cristo de Burgos met its end.

Unlike its fictional counterpart in The Goonies, the real-life Santo Cristos de Burgos is not believed to have been transporting a pirate’s treasure. However, the recovery of the ship gives a nod to our favorite fictional motley crew, and inspires us to ponder questions of ownership when an underwater shipwreck is discovered by a private citizen. Specifically, what are the legal, financial, and cultural dynamics at play when a salvor brings a shipwreck to the surface?

The answer may be surprising.

The Goonies may have led you to believe that the finders keepers rule applies to pirate treasure Unfortunately, in practice, a person that salvages items from a ship or that have been lost at sea (also known as a salvor) may lose the gold and the glory. This raises the question: what should a salvor expect to receive if he or she successfully unearths a sunken ship? Should Mikey’s family rest easy with its bag of recovered “rich stuff”? Or should older brother Brandon get to mowing his 377th lawn? To answer those questions, a few laws come into play.

Salvage Law

Traditional principles of salvage law dictate that the salvor of an underwater artifact may claim possession if the artifact has been abandoned (for example, Ariel’s grotto of “things” in Disney’s The Little Mermaid are her gadgets and gizmos for keeps, if she is able to demonstrate abandonment by the original owners). Even if an artifact has not been proven to be abandoned, the salvor may still recover under this law through a “salvor’s award” given by the state. This award can be substantial, reaching as high as 90% of the total value of the recovered property.

Recovering shipwrecks

The recovery of shipwrecks, in contrast to underwater artifacts, tends to be governed by a combination of federal laws (such as the Abandoned Shipwreck Act and the Sunken Military Craft Act), various state statutes (though these vary depending on the state; Nebraska, for example, has limited salvage laws, as not many shipwrecks are recovered in the Cornhusker State), and international law. For example, the UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage mentions the law of salvage and the law of finds in its Article 4.

These laws heavily tip the scales in the favor of state, federal, and even international interests over a salvor’s potential payout. If a salvor does bring a claim to a shipwreck and relies on traditional salvage law, the salvor’s claim will likely lose to the challenger under these tests, because the burden to show abandonment (crucial for a salvor) is subject to a higher standard.

The Abandoned Shipwreck Act

Under the Abandoned Shipwreck Act (43 U.S.C. §2105-06) (which claims ships found more than 22 km offshore as federal property), a salvor who wishes to claim ownership of a recovered shipwreck must prove both a long period of no use or search by the original owner and the express intent to abandon.

Under the Abandoned Shipwreck Act (43 U.S.C. §2105-06) (which claims ships found more than 22 km offshore as federal property), a salvor who wishes to claim ownership of a recovered shipwreck must prove both a long period of no use or search by the original owner and the express intent to abandon.

Courts are increasingly reluctant to find that the original owner of property has exhibited an express intent to abandon, particularly when the technologies used to recover these centuries-old shipwrecks today did not exist at the time of the alleged abandonment.

Moreover, courts have been impressed by parties who immediately reclaim ownership when news of the recovery is made public, even when the interested party has not actively been searching themselves.

This was the case in People ex rel. Illinois Historic Preservation Agency v. Zych. There, the court ruled in favor of an insurance company claiming the interest to the recovered vessel Lady Elgin. The court’s decision turned on the fact that the company (who was responsible for covering the ship’s voyage) produced centuries-old documentation of a paid insurance claim (dated prior to the invention of the telephone) once the suit was underway. This not only won the insurance company rights to the ship, it also validated the longevity and thoroughness of their internal filing system.

The Sunken Military Craft Act

Even assuming a salvor can surmount the obstacles posed by the Abandoned Shipwreck Act, our treasure hunter may still stumble when faced with the Sunken Military Craft Act (2004).

This Act awards possession of any vessel on a military mission to the ship’s country of origin, even if the country does not attempt to claim ownership until centuries later. While this seems like an easily recognizable classification, it presents an unusual challenge, because most of the ships coming to America in its early days contained some kind of artillery on board for the safety of the crew (and, possibly, a bit of pillaging on the side). That means that most any ship carrying cannons or other traditional weaponry could feasibly qualify under this test, leaving the salvor with no rights in the face of an interested claimant nation.

The UNESCO Underwater Heritage Convention

Finally, even if the salvor manages to maintain rights in the vessel after all of the aforementioned tests, the claim may still be lost when faced with the UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage, an international treaty protecting underwater cultural heritage. Unfortunately for salvors hoping to receive a quick pay-out, Article 4 of this law abandons the law of salvage completely, unless the interested country authorizes the salvage in accordance with the treaty and whatever is recovered is given the highest protection under the applicable country’s law.

Even though the United States is not a party to this treaty, many nations who colonized the United States are, including Italy, Spain, and France. This means that it is certainly an important law that salvors should be aware of, lest they be caught unawares, because of the sheer number of ships lost by these colonizing nations at that time.

What’s at stake?

Finding a shipwreck and recovering a bounty is not simply about saving one’s family from financial ruin, as was the case for Mikey and his gems. Proper recovery of the cultural heritage embedded in shipwrecks, as well as the preservation of priceless pieces of history, is essential to constructing a comprehensive narrative of global history. Things that traditional salvors may discard, accidentally destroy or damage, or overlook – such as pieces of fabric, newspaper, and even teeth and nails – are prized by states, nations, and archaeologists due to their incredible insight into the lives and societies of the people who sailed the ocean blue. And so, treasure hunting – while thrilling – if not done properly, may come at an incredible cost.

So, if you do find a treasure map in your attic and begin your own quest to recover galleons from a shipwreck, consider the balance of state, federal, international, and cultural interests at play. And, before you call the bank with that bag of jewels to save your home from foreclosure, call an art and cultural heritage law attorney to protect your rights.