“Continue to take all the risks and forever be curious.” – Shannon Riley, Co-founder of Building 180

In celebration of International Women’s Day, we are highlighting women in art history. Some readers may be unaware of the sheer number of working female artists during male-dominated artistic eras. If, for example, the Italian Renaissance only calls to mind the names of Ninja Turtles, and leaves out Italian Renaissance pioneer Fede Galizia, then this is a post to bookmark.

Fede Galizia (Italian, 1578–d. ca. 1630); Still life of peaches on a fruit stand with jasmine flowers and a tulip. Image obtained via artnet.com

Who was Fede? Not only the holder of an unusual name, which Microsoft Word is currently attempting to autocorrect to “FedEx,” but she was a female painter making strides in the art world alongside other Italian Renaissance greats. Her contribution to the still life genre may be compared with that of Caravaggio’s. Both were composing still lifes of fruit within the same decade – a rarity for this artistic era.

Details about Fede’s early life are few and far between, but it is likely that she faced societal pressures to prioritize domesticity over artistic training. But her knowledge of the household, gained by living with family throughout her childhood and early life, may have worked in her favor. It could be argued that her intimacy with domestic life gave her an edge in creating her iconic still lifes, over male counterparts like Caravaggio. If the men in her life thought that her obsession with making precise, detailed studies was “cute,” they were in for a surprise. Unbeknownst to them, this powerhouse of an artist was creating works that some critics today say surpass the skill and precision of her male counterparts. Her still life of peaches on a fruit stand with jasmine flowers and a tulip? Stunning. Take that, Caravaggio!

Fede also created distinctive miniatures, portraits, and altarpieces with incredible dedication to detail gleaned from her daily life. Her rendition of Judith with the Head of Holofernes, for example, purportedly features Judith as the self-portrait of the artist. The boldness required to use her own visage as inspiration speaks to the internal fortitude required for her to make art despite any societal pressures to engage more fully in domestic life.

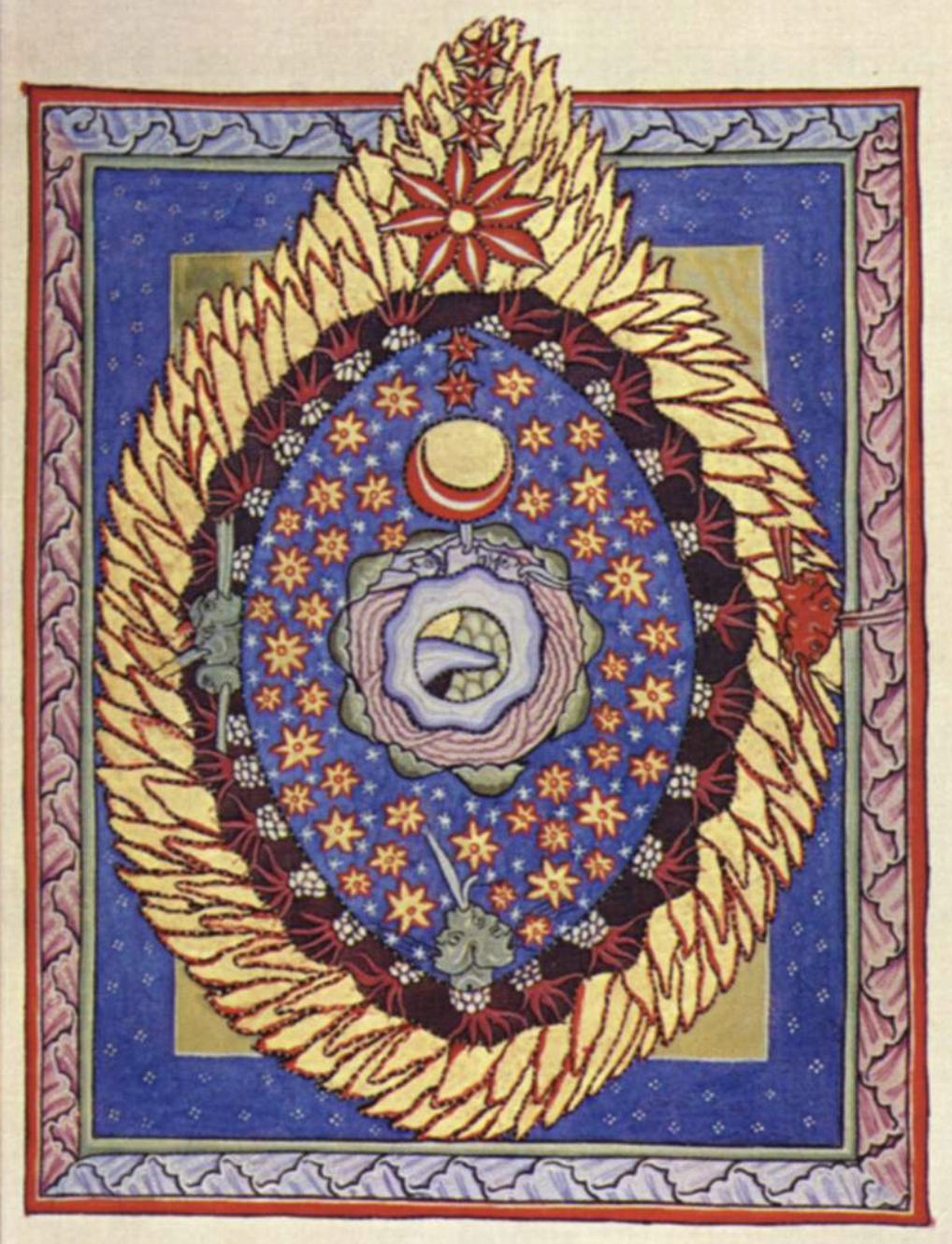

Hildegard von Bingen, Scivias, 1151. Image distributed via DIRECTMEDIA in public domain.

Another historical standout is the one-and-only Hildegard von Bingen, largely regarded as the original female artist. Hildegard von Bingen was a woman in possession of the ultimate multi-hyphenate of a bio. Ready? She was an artist/composer/writer/Catholic mystic/scholar/modern-day Catholic saint/ and one of four female Catholic Doctors of the Church. She was a busy woman. In terms of her artwork, she is particularly known for her illuminated manuscript Scivias, (or “Know the Ways”), created around 1150. This manuscript contains illustrations of a mystical vision she had. The vision revealed the universe to her as a “round and shadowy” composition that was sheathed in an “outermost layer of a bright fire.” To Hildegard, this vision spoke to the breath of life awakening the universe. Her use of dramatic themes, and her openness with her own mystical visions, reveal a tenacity of a woman who was bold beyond the cultural norms of women of the time.

If either of the above artists’ stories are new to readers, join the club – many women artists have been written out of traditional art canons. As a result, even art history majors may not know of as many female artists as they do male ones. Sadly, many female artists simply failed to gain recognition, despite their talent and genius.

Sculpture in SoMo Village. Artists: Joel Dean Stockdill and Yustina Salnikova. Located in Rohnert Park, CA. Image via Building 180.

Fortunately, today, tides are turning, and there has been a renewed, concentrated effort to remember women in art across the ages. Our firm previously wrote an in-depth post on women and the rediscovery of women artists. Read it here. The efforts to recognize previous women artists are essential in crafting a more complete and cohesive global artistic narrative across genres, genders, and stereotypes.

As important as it is to remember those women artists of yesterday, we also celebrate women in the art world today. Women are making bold moves in the art world, as artists, scholars, patrons, and business entrepreneurs. Included in this group is the standout women-owned business Building 180.

Building 180: Finding a Space & Filling a Need

Bee Line sculpture installed for Piatt Park. Artist: Inflatabill. Located in Cincinnati, OH. Image via Building 180.

Building 180 is a full-service global art production and consulting agency. The company fills the gap between artists and businesses to create public and private art installations in the form of murals, sculptures, and interiors. “Full-service” here means “full-service”: Building 180 handles the design, curation, and production of art installations from conception to completion. This includes budgeting, contracting, artist selection, fabrication, shipping, and management. Building 180 really shines in its role as intermediary, by streamlining communication between artists and site owners to make a smooth installation of the artwork (whether permanent or temporary).

IT interior created for Twitch. Muralist: The Tracy Piper. Located in Los Angeles, CA. Image via Building 180.

Think of Building 180 as the Fairy Godmother of Cinderella’s art world: giving oft-overlooked artists their Glass Slippers and sparkly pumpkin carriage to arrive at the ball. Building 180 provides artists with the essentials needed to bring forth their best work, while simultaneously handling the often overwhelming logistical and business aspects of large-scale installations. The result is an open, approachable, communal experience of art living alongside viewers in the everyday.

The need for a business such as Building 180 cannot be undervalued. Contrary to popular belief, murals, sculptures, and gorgeous interiors do not simply appear overnight. They require attention to detail at all stages of the transaction. Because Building 180 orchestrates the installation from start-to-finish, working with both artists and business owners, the company makes the murky waters of bringing art to life in unexpected places not only possible, but peacefully navigable.

Bringing Art to the Community

Muralists stand back to gauge their work for Paint the Void. Image via Building 180.

At the heart of Building 180’s mission is to bring art to the community through strategic efforts to foster engagement and inclusivity. These goals are achieved through educational programming, invitations for project volunteers, and panel discussions aimed at identifying the needs and desired outcomes for the community.

The premier example of Building 180 bringing art to the community in an effective and mindful way occurred in the early stages of the pandemic lockdowns of March 2020. Paint the Void, Building 180’s non-profit, is the public mural initiative founded in early 2020. The goal of the organization? Commission artists to complete public murals using the plywood covering closed storefronts and windows of boarded-up businesses. The result has been a completion of over 230 murals. Building 180 partnered with over 35 different neighborhoods to install the works. In doing so, Building 180’s brilliant team has supported over 175 small businesses, engaged the help of over 2,000 volunteers, and seen 250 artists paid for their work.

A ”snapshot” of this mural movement was recently on display in San Francisco, in the form of a retrospective. The City Canvas: A Paint the Void Retrospective featured 49 pieces from Paint the Void, including Nora Bruhn’s Keep Blooming, a pastel-colored floral that covered the boarded-up storefront of restaurant Chez Maman.

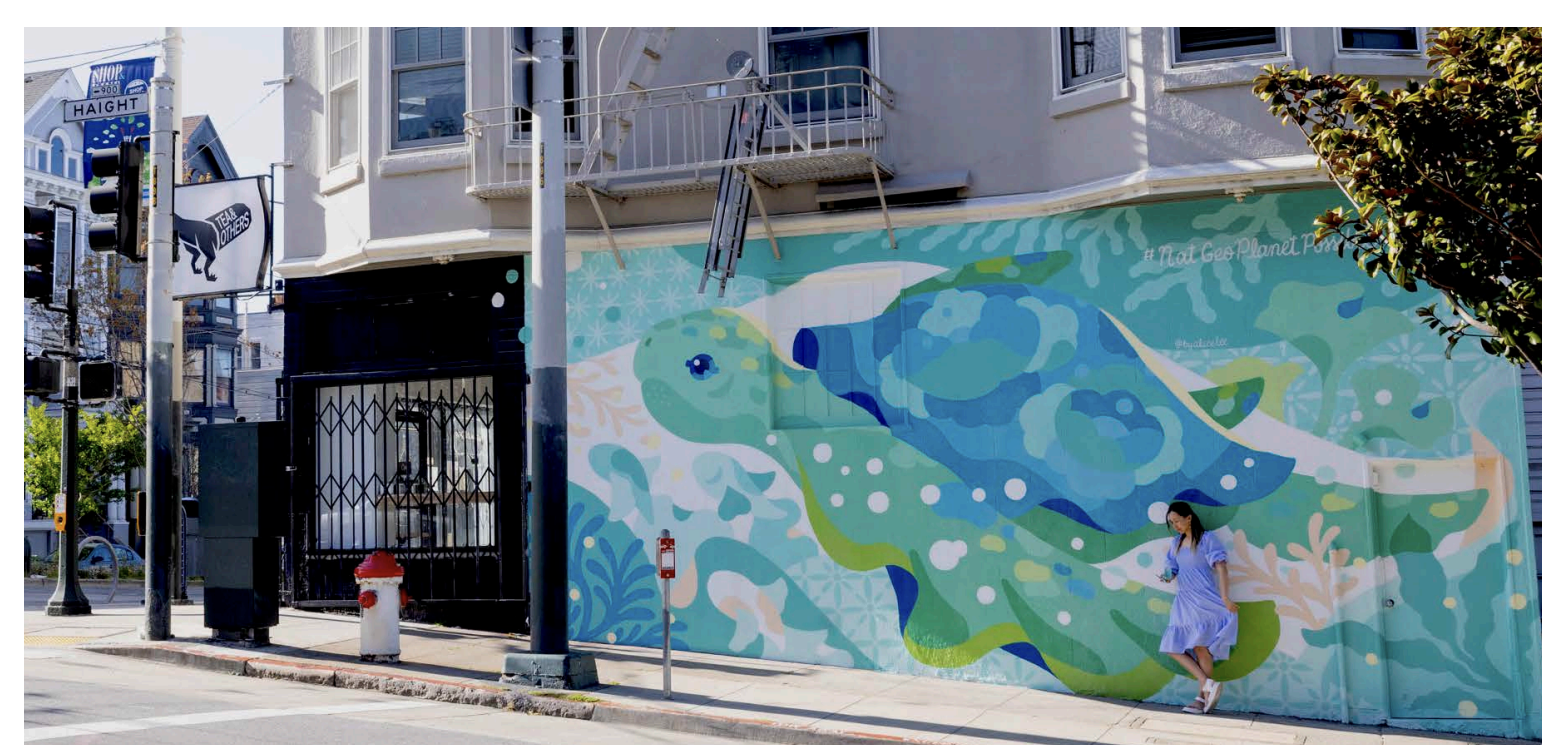

Save the Turtles painted for National Geographic. Artist: Alice Lee. Mural located in San Francisco, CA. Image via Building 180.

Bruhn’s piece is a fantastic example of the fundamental impact of the mural movement, and of Building 180 as a whole: to release the artistic power held within the daily lives of local communities. Building 180 accomplishes this impeccably, by marrying artists with businesses to find available space for art. These creative solutions employ artists and create economic opportunities for business owners – all while serving to spark the imaginations of all who encounter the works. The result? Communal resiliency and a deeper fascination with the power of art.