by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Sep 29, 2023 |

By: Maria T. Cannon

Due to the Azerbaijani regime’s military aggression last week, over 100,000 Armenians have fled the Republic of Artsakh (also called Nagorno Karabakh) in just four days. Azerbaijan’s military assault followed its nine-month-long illegal blockade of the entire region. For those Armenians who have called this land home (Artsakh became part of the Kingdom of Armenia in 189 BC and has maintained a majority Armenian population since then, despite being subjected to various invading rulers), fleeing their ancestral lands is necessary for survival. The alternative is to be subjected to the whims of a petro-dictatorship that openly conveys its formal policy of anti-Armenian hatred and belief that Armenians have “no right to live in the region.”

Gtichavank Monastery in Hadrut (2015). Used with permission from Yelena Ambartsumian.

Heartbreakingly, the exodus of Armenians and Azerbaijan’s occupation of the region leaves Armenian art and architecture unprotected, and we are already seeing videos of Azerbaijani soldiers shooting at and desecrating cultural heritage from Azerbaijani social media channels (international reporters are not able to access the region). Artsakh is known as the “Crown Jewel” of Armenian cultural heritage, as it contains some of the most exemplary representations of medieval Armenian architecture, as well as important sites such as the first school to teach the Armenian alphabet in the early fifth century.

War Crimes, Human Genocide & Cultural Genocide

It is a story well-known to regions in the throes of war: the searing pain of losing one’s home is compounded by the risk posed to cultural heritage left behind. In international law, war crimes, crimes against humanity, ethnic cleansing, and [human] genocide are defined separately from cultural genocide. However, all usually include acts of cultural genocide, due to the nature of the crimes committed.

Evidence of cultural genocide can be used to help prove the special intent required for the crime of genocide. This is largely because the two are so closely connected. In fact, modern experts urge legal professionals to understand that cultural genocide is “as old as [human] genocide itself” and may (in fact) be virtually inseparable from human genocide.

In light of the current situation in Armenia, and past actions by Azerbaijani forces in Artsakh— coupled with Azerbaijan’s complete eradication of over 100 medieval monasteries and thousands of cross-stones in its exclave of Nakhichevan during “peacetime”—it is an almost certainty that Azerbaijan will continue to destroy Armenian cultural heritage. Moreover, because global cultural heritage organizations such as UNESCO, have failed to uphold their own organizational standards, and other entities such as the EU have refused to condition their purchases of natural gas from Azerbaijan on Azerbaijan’s respect for cultural heritage, there is an even higher likelihood that Azerbaijan will continue to act with impunity.

Gandzasar Monastery in Martakert (2015). Used with permission from Yelena Ambartsumian.

UNESCO’s Failure

UNESCO, known globally for championing world cultural heritage, has failed the Republic of Artsakh. On September 19, 2023, UNESCO launched a well-meaning (but utterly toothless) Armenia National Statement of Commitment Knowledge Hub and a similar Armenia National Consultation Report Knowledge Hub. The online portals come across as a futile attempt to maintain a presence in the real-life devastation currently unfolding. At this stage in the military regime’s progress, resources should be used to assist humanitarian and cultural preservation efforts on-the-ground—but Azerbaijan simply refuses to guarantee safe access to UNESCO monitors.

Both UNESCO’s current response and its lack of action in the months leading up to these (foreseeable) events are frustrating. Armenians have come to terms with UNESCO’s inability to protect their cultural heritage in this situation. The reasons UNESCO has been so ineffective are primarily two-fold: the first is the UNESCO’s Second Protocol lacks the enforcement mechanisms needed to (1) prevent cultural heritage destruction by states who are bad actors and (2) punish states that do. The disadvantages on relying on an organization such as UNESCO are compounded when the cultural heritage at issue resides in an area that UNESCO does not recognize as a “state.” The Republic of Artsakh falls under this category (meaning, UNESCO does not recognize it as a “state” of Armenia). UNESCO even failed to send a mere fact-finding mission to Artsakh, due to Azerbaijan’s objections.

The small crumb of good news is that the Armenian people took initiative and found a brilliant way to enforce global protection of their art and cultural heritage. As a law firm dedicated to protecting art and cultural heritage, we applaud the Republic of Armenia for developing this framework and precedent. We also are heartbroken that, as a nation, they were forced into developing this sort of legal path while a humanitarian crisis is currently ongoing.

Dadivank’s khachkars (2015). Used with permission from Yelena Ambartsumian.

ICJ’s Decision and CERD

Instead of going through the UNESCO conventions, which inherently apply only to recognized states (and have therefore left out Armenian cultural heritage within the currently unrecognized Republic of Artsakh), Armenia instituted a case against Azerbaijan before the International Court of Justice (“ICJ”) under the CERD—the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination—a United Nations treaty to which both Armenia and Azerbaijan are party.

The ICJ ruled for Armenia in its orders on provisional measures, stating that Azerbaijan must cease their state-sponsored destruction of Armenian art and cultural heritage in Artsakh.

With an ICJ order, which the U.N. Security Council is responsible for enforcing, the Republic of Armenia was able to create a new tool for safeguarding Armenian cultural heritage. Under Art. 94(2), member states are required to comply with ICJ orders. This means that Azerbaijan is clearly in violation. The U.N. Security Council has never before had to impose punishments (usually, simply the threat of involvement and diplomatic pressure from other nations are enough to stop the harm being done). However, in this case, action may not only be warranted, but is necessary to prevent Armenian culture from being erased from this region.

In an interesting update, the Republic of Armenia filed a request for indication of provisional measures against Azerbaijan, under the Armenia v. Azerbaijan proceedings before the ICJ on Sept. 29, 2023. In the filing, the Republic of Armenia specifically asked the Court to reaffirm Azerbaijan’s obligations under the Orders it rendered previously (stating, “in particular those of 7 December 2021 and 22 February 2023.“).

The importance of protecting the art and cultural heritage in Artsakh cannot be undermined. Why? Read on.

Fresco in Dadivank (2015). Used with permission from Yelena Ambartsumian.

Armenian Crown Jewels at Risk

Armenian cultural heritage has been under attack for some time. For evidence, turn to the fate of Armenian culture in the Caucasus under Azerbaijani occupation. Nearly all Armenian heritage sites in Nakhichevan were destroyed by Azerbaijan during “peacetime.” Satellite imagery by the Caucasus Heritage Watch from November 2022 confirmed that 98% of Armenian cultural sites were completely destroyed. Devastatingly, such annihilation was the result of state-sponsored, orchestrated destruction by Azerbaijani officers. To date, Azerbaijan denies destruction and instead claims that Armenian cultural heritage never existed in Nakhichevan.

Artsakh’s treasures are incredibly vulnerable in light of recent aggression by Azerbaijani forces. This is devastating to the Armenian and global artistic, religious, and historical academic communities, because Artsakh is referred to as the crown jewels of Armenian culture due to the massive number of sites from antiquity to the medieval ages, as well as cave complexes with some of the earliest evidence and remains of various hominid species in Eurasia (after crossing from Africa). In addition to having ties to Armenian nobility, the art, artifacts, and architecture in Artsakh are vital to understanding and appreciating Armenian culture. Armenians themselves reported emphasize the significance of Artsakh by saying, “after all, the crown of the ancient Kingdom of Armenia is in Nagorno-Karabakh [Artsakh].”

The entire region presents a stunning encapsulation of Armenia’s art and history. Early historical monuments and ancient fortresses reflect pre-Christian influences, while later expressions such as illuminated manuscripts, ecclesiastical murals, cross-stones, and religious structures embody the heritage of one of the world’s oldest, indigenous Christian populations. Below are two specific Armenian cultural crown jewels, currently under attack.

Ghazanchetsots Cathedral in Shushi (2015). Used with permission from Yelena Ambartsumian.

Shushi

The city of Shushi, in Nagorno-Karabakh, is a true Armenian cultural crown jewel. Shushi came under occupation by Azerbaijan in November 2020. Before and after gaining control of Shushi, Azerbaijan intentionally attacked its Armenian cultural heritage. In fact, in October 2020, it shelled the beautiful Ghazanchetsots Cathedral not once, but twice. There was no evidence that the shelling qualified as a military objective, particularly as civilians were hiding in the church (and the second shelling occurred when international journalists arrived to cover the destruction —one journalist was killed).

Ensuing coverage of the cathedral revealed graffiti on the walls, with Azerbaijani leaders marching through the sacred space. Precious manuscripts and relics, such as the Right Arm of Grigoris—the Catholicos of the region and grandson of St. Gregory the Illuminator who

converted Armenia to Christianity in the early 300s—are feared to be lost.

Azerbaijan then began its own “renovation” of the cathedral (deemed by the Azerbaijani Ambassador to the Holy See Ilgar Mukhtarov as a corrective effort to return the cathedral to “its original appearance [prior to Armenian cultural influence.]” This “renovation” was not done in consultation with the Armenian Apostolic Church and instead involved “beheading” the cathedral by removing its pointed dome—a hallmark of Armenian church architecture. Azerbaijan also destroyed another church in Shushi—the “Kanach Zham” (Green Chapel) Armenian Church of St. John the Baptist—by removing its pointed cupola.

The devastation is reminiscent of proto-Azerbaijani armed forces’ destruction of Shushi in 1920, which were supported by the Ottoman Army, as it marched eastward to try to take control of the region amidst the Armenian Genocide. At that time, the Ghazanchetsots was also targeted and vandalized, in addition to other significant Armenian cultural heritage sites. Half of Shushi was revealed to be destroyed, as the unrecognized Azerbaijan Democratic Republic carried out a “cultural de-Armenianization” of Nagorno-Karabakh. Current reports and photos of the region now under occupation prove that the cultural jewels of the city are – once again – suffering intentional destruction at the hands of Azerbaijani military forces.

Dadivank

Dadivank is another important cultural jewel that has fallen under Azerbaijani occupation. This is an unprecedented loss, as the Dadivank region is a spiritual center for Armenian Christians. Dadivank contains an important religious complex, known as the Dadivank Monastery, which houses the relics of St. Dadi, a disciple of Thaddeaus the Apostle, in addition to other sacred artifacts and objects. Because the land is now under Azerbaijani control, irreplaceable symbols of Armenian spiritual and religious heritage are in danger.

The monastery itself encompasses a series of more than thirty buildings on its territory. This includes several churches, chapels, monasteries, libraries, and living quarters, as well as the Hasan-Jalal Palace (and even a printing press!). Cultural highlights include works such as the frescos on the walls of the Church of the Holy Virgin (built in 1214 by Princess Arzu-Khatan, and the porch-chapel of St. Grigor (built in 1224 as the burial vault of princes).

Another priceless piece of Armenian cultural heritage is located on these grounds: khachkars, or cross-stones (stone slabs with engraved crosses). These are irreplaceable components of the Armenians’ cultural legacy, because they are exclusive to Armenian religious art (and have been for centuries). Many of the khachkars located in the St. Dadi Church, for example, date back to the 12th and 13th centuries. Unfortunately, because these works are so closely tied to Armenian Apostolic Church identity, khachkars and other works of ecclesiastical art and architecture are prime targets for Azerbaijani destruction.

Ruins of Shushi after the city’s destruction by Azerbaijani army in March 1920. In the center: defaced Armenian Ghazanchetsots Cathedral. Image via State Archives of Armenia (public domain).

Global Response

Armenians who have been able to flee recount the bombing, fear and death they have left behind. Their first-person accounts give us a clearer insight as to what is truly going on in Artsakh – both to ethnic Armenians and to their cultural and artistic treasures. Reports of attacks done with “no apparent regard for the lives or basic human rights of the population of Nagorno-Karabakh” explain the seriousness of the situation.

Armenian art and architecture carry incredible significance – not just in Armenian culture, but as a vital piece of our shared global human narrative. The works being destroyed are testaments to their artistic mediums – gorgeously decorated and elaborately intricate. More importantly, they are symbols of the history of Armenia as a liberated people.

Many of these cultural heritage sites have served as pilgrimage destinations for Armenians for centuries. Even apart from the significance to Armenian culture, the sacred works and spaces are a testament to pre-Christian medieval influences, early Christian artistic works, and the 19th and 20th century religious-cultural renaissance of the region.

All can do their part in raising awareness of the on-going crisis in Armenia. In addition to continuing to pressure government officials to take action, make a donation through a trusted relief organization.

Donate to the Armenian Red Cross here.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Sep 29, 2023 |

Our founder, Leila Amineddoleh, has recently been featured in New York Metro Super Lawyers Magazine, alongside other leaders in her field. Leila was chosen for the piece as a top-rated intellectual property, art, and cultural heritage lawyer well-known in the industry for getting the job done right. This means advocating both for her clients, and for the art and cultural heritage at issue.

Our founder, Leila Amineddoleh, has recently been featured in New York Metro Super Lawyers Magazine, alongside other leaders in her field. Leila was chosen for the piece as a top-rated intellectual property, art, and cultural heritage lawyer well-known in the industry for getting the job done right. This means advocating both for her clients, and for the art and cultural heritage at issue.

In the article, Leila’s experience working with our former client (and now current friend) Laura Young, is highlighted. Young is our client who found an Ancient Roman marble bust at her local Goodwill in Austin, TX. Our firm has written previously about Leila’s and Laura’s story. Read the incredible journey one Roman bust took from Germany to Texas (and how he found his way home) here.

In the piece by Super Lawyers, Leila’s success working with Laura is illustrative of her signature manner taking care of her clients by providing insight on best practices in the art law field. In Leila’s words, her work as a lawyer requires giving this special level of attention. She says it can require coming up with “creative solutions . . . . As a lawyer, you find out what’s important to someone.”

Later in the article, Leila gives her thoughts on changing attitudes on lawsuits involving stolen antiquities. She connects the rise of modern lawsuits brought by claimants for contested works to a 1995 international investigation in Italy. That investigation exposed many thought-to-be honest dealers as thieves, and revealed and auction houses to be engaging in deceptive practices. Leila explains how the impact of this investigation continues to call objects held by museums, collectors and auction houses into question, leading to an on-going return of hundreds of objects and works of art.

Leila’s success has launched her and her namesake firm to even greater heights. It is an honor to be featured alongside other esteemed colleagues this stand-alone piece. In it, Leila and her colleagues give important guidance on the current industry challenges for art lawyers. Read the piece here.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jul 27, 2023 |

Roman Forum. Image via Fodor’s, available at https://www.fodors.com/world/europe/italy/rome/experiences/news/photos/the-10-best-ancient-sites-in-rome.

Our firm is pleased to continue our collaboration with the American Institute for Roman Culture (AIRC) in their Ancient Rome Live Series. Those familiar with the AIRC’s work will remember our firm’s past contributions to the series, which are available here.

For those who are just learning of AIRC and their work, the AIRC is an internationally-acclaimed non-profit founded in 2002 to promote Italian culture. AIRC provides opportunities for education, archeology, and study abroad, with locations in both the U.S. and Italy. AIRC’s founder, Darius A. Arya, is an archeologist, public historian, author, social media influencer, and TV host based in Rome, Italy. In his role as AIRC CEO, Dr. Arya leads lecture series, heritage preservation initiatives, teaches bespoke educational courses, and hosts a highly-rated podcast called Darius Arya Digs.

Colosseum. Image via Fodor’s, available at https://www.fodors.com..

Our firm’s most recent contribution tackles the complicated (and extremely timely) issue of overtourism. Following the opening of international borders, tourists have flocked to cultural heritage hotspots around the globe. The sudden influx of tourism to cultural heritage sites seems to be a symptom of “revenge tourism,” the product of isolating at home during the pandemic. While re-engaging with travel in a thoughtful way no doubt fuels local economies and broadens the mind, thoughtless travel often results in the destruction of priceless pieces of cultural heritage.

Interested? Read the entire article on the Ancient Rome Live Series website, here.

AIRC has been an awarded an NEH grant, an American Express Foundation grant, and a World Monuments Fund (WMF) collaboration. AIRC receives additional funding from anonymous angel investors and individual donors. If you would like to contribute to AIRC and Dr. Arya’s world-class courses and promote opportunities for lifelong learning, you may support the organization here.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jul 24, 2023 |

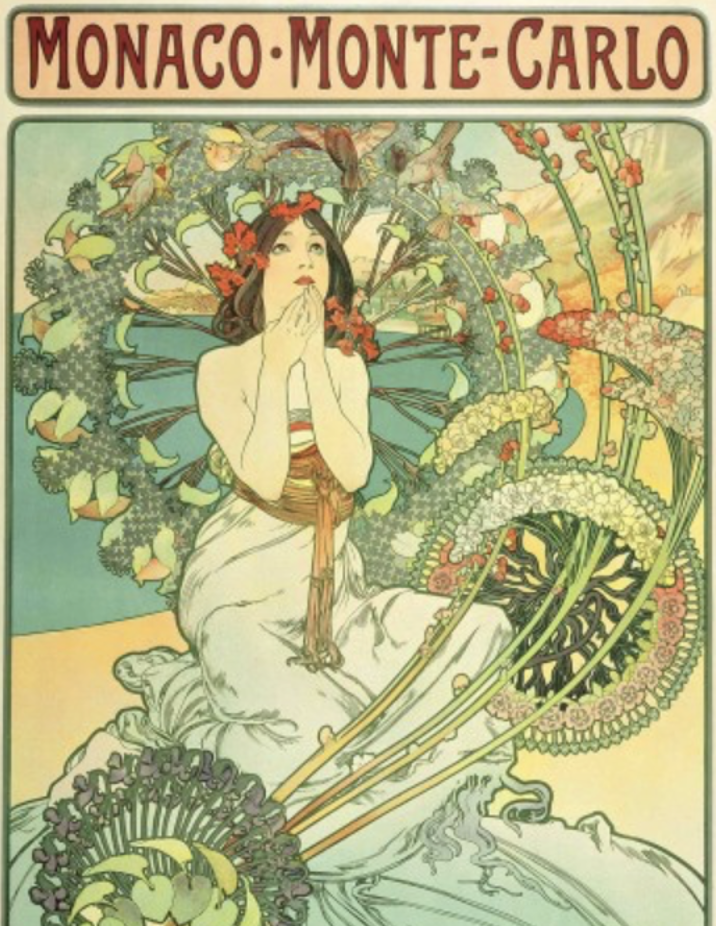

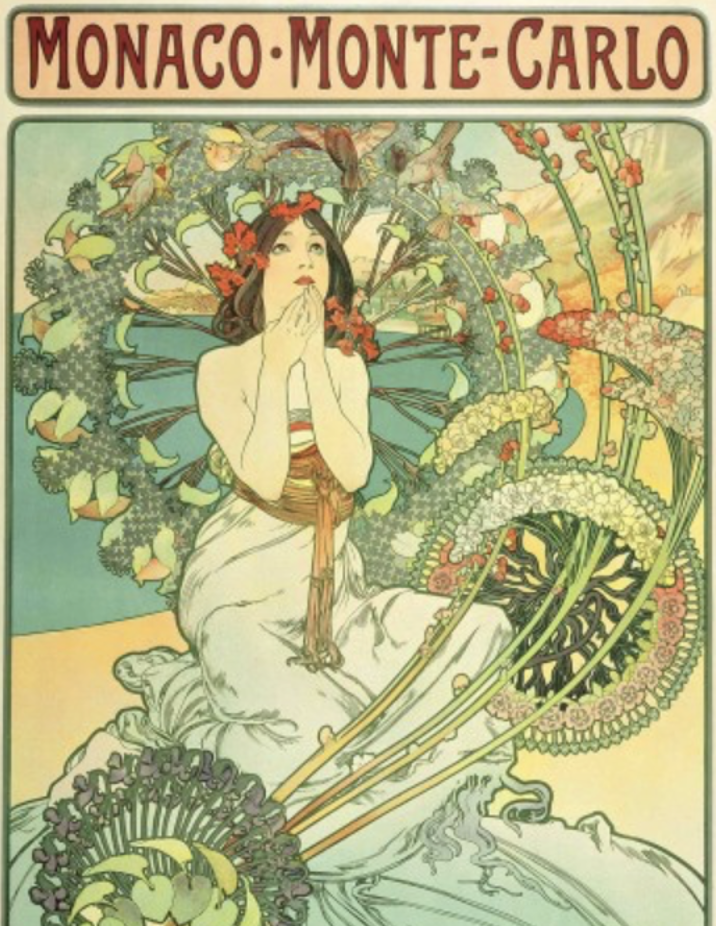

Art Nouveau fans rejoice: July 24th is the late Alphonse Mucha’s birthday. This year’s anniversary comes with a bit less fanfare than his 150th in 2010, when Google created a doodle on the artist’s behalf.

But even without a doodle from Google, Mucha’s legacy continues to influence art and artists around the world. One aspect of his enduring legacy is how his work influenced the rise of celebrity art. This phenomenon has been popping up more and more frequently in American culture, and no one (not even celebrities themselves) are immune from the draw of star power.

Modern Celebrities Embrace Art

No longer playing the role of pirate, actor Johnny Depp has swapped his sword for a paintbrush in real-life. It seems to have been a sound business move. The actor made a staggering $3.6 million selling works from his first “Friends & Heroes” art collection in 2022. His second, entitled “Friends & Heroes II” was released in February. It is comprised of four portraits of artists that have inspired Depp throughout his life: Bob Marley, Health Ledger, River Phoenix, and Hunter S. Thompson. An unbelievable answer to the classic “Dream guests at a dinner party?” question, if ever one existed. Almost already entirely sold out – all that remains on the Castle Fine Art website is a pack of all four prints, priced at a swashbuckling $20,416.67.

Depp’s foray into celebrity art highlights modern culture’s fascination with all-things celebrity. Are Depp’s works prized due to his creative talent as an artist? Or are the pieces selling because they are exclusively of famous celebrities? Or, possibly, Depp is able to sell out faster than Taylor Swift tickets because he, himself, is a celebrity? Which points to the threshold question: when did artists begin to feature celebrities in art? Many art historians look no further than the incredibly gifted Alphonse Mucha, who skyrocketed his own career to greater heights through his collaboration with a famous actress.

Rise of Celebrity Art

“If you have to explain to someone you’re famous, then you’re technically not that famous.”- David Spade.

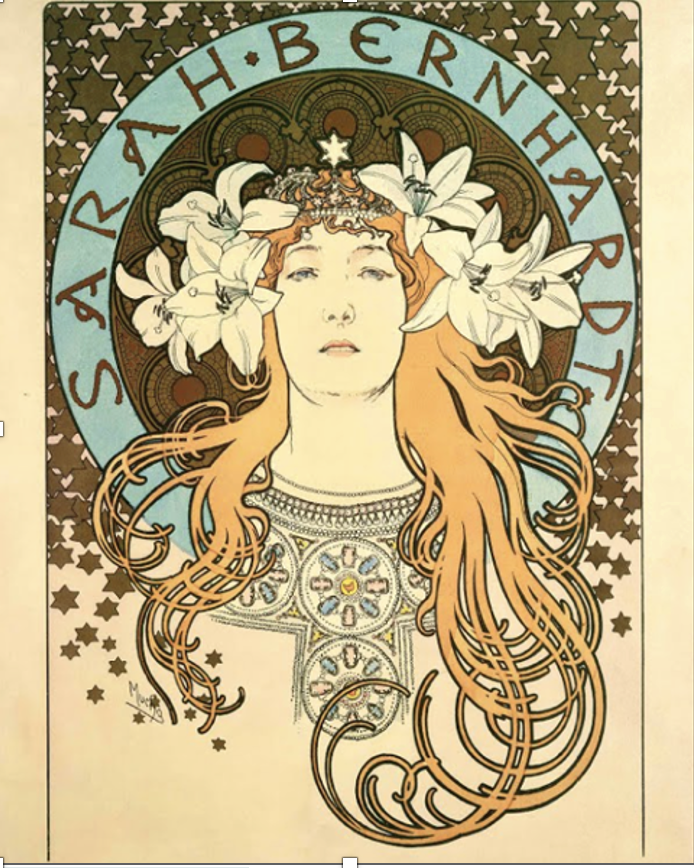

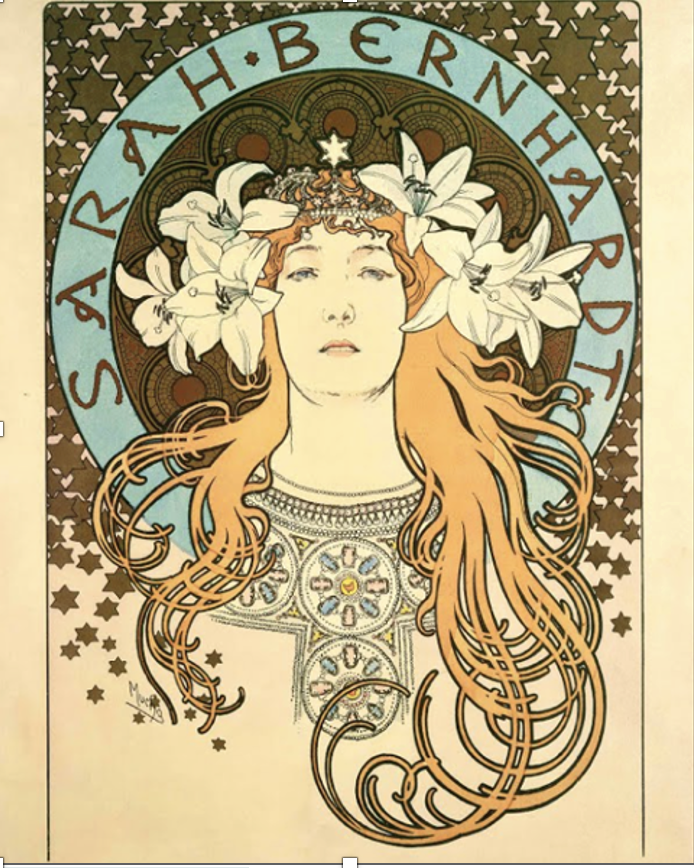

The beauty of Alphonse Mucha‘s work stems from his deep passion as an artist. Many artists are known for having a lot of gusto, but Mucha really takes the cake. He was master of the Art Nouveau style of art, so masterful in fact that many credit his career for influencing major tenants of the age – politics, religion, philosophy, and – of all things – the career of one very famous actress named Sarah Bernhardt.

Alphonse Mucha, Poster for ‘La Plume’ magazine (1897). Image via muchafoundation.org.

Before we get to Sarah, a little more about our man Mucha. He was born on July 24, 1860, in a quiet town in Moravia. In his youth, Mucha was – in his own words – “preoccupied with observing.” This tendency to notice things around him manifested in a profound artistic talent. Young Mucha could be found making sketches and drawings for friends, family, and fellow townsfolk. His drawings were so prodigious that he collected quite a few fans, even in his early days. One fan was the town’s shopkeeper, who often slipped Mucha free sheets of a paper – a luxury of the day – in order for him to make his creations.

As Mucha grew older, his artistic talent also matured. When he was 18, he was ready to apply to the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. Unfortunately, he was rejected. The admissions office even went as far to suggest he take up a different, “less artistic” career. I’m not sure what they had in mind (medical school?), but fortunately for us, Mucha was not discouraged for long. He decided to simply carry on and continued to make art in whatever way he could.

A year later, Mucha had a bit of luck – an opportunity arose for an artist to work with a Vienna newspaper making advertisements. The pay was pitiful, and Vienna is freezing cold in winter. However, Mucha forged ahead, desperate to create. He applied, scored the gig, and packed his bags for his journey to the big city.

This was a turning point in Mucha’s development as an artist. He spent two years in Vienna, creating advertisements for the paper by day and taking art classes by night. What this did was cement in him a love for creating artwork that was accessible to the average, everyday person. He thrived on creating beauty in pamphlets, posters, and advertisements that most companies and institutions did not have the time or talent to make elaborate. We can start to see, from this period, the development of certain curvature in his lines, and repetition of old world-inspired motifs come up again and again in works that would inevitably become a part of an ordinary person’s daily life.

Mucha retained this love of creating beautiful and accessible work, while still seeking to enhance his skill as an artist through more formal training. Eventually, he applied to – and was accepted to enroll in – the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich in September of 1885. This provided Mucha with formal artistic skills, though it is important to note that Mucha is still believed to be largely self-taught as an artist (which could also mean that he ignored much of what was taught in school). From Munich, he made his way to Paris: the art capital of the world at the time.

In the City of Lights, he established himself as a “reliable” illustrator (as noted by his biographers). The Paris theater scene is where the lives of Mucha and the phenom Sarah Bernhardt intersect. Sarah Bernhardt is often touted as the original “true superstar.” This is before the current fame-cycle of Hollywood starlets, who now can be seen as a dime a dozen, splashed across the covers of People magazine.

Sarah Bernhardt was the real-deal – a woman with the poise, charisma, and gumption to make a name for herself as an actress against the backdrop of a politically tumultuous city. Not only is she remembered as a strikingly impactful actress, known for her talent, she is also regarded as the first superstar known to personally exploit her own image and likeness for economic gain, and to raise her own fame. This is an important piece of the puzzle of a topic referred to as “publicity,” which we’ll address later.

Mucha began working with Bernhardt in December 1894, in a serendipitous sort of meeting that can only be attributed to fate. Bernhardt’s play, Gismonda, was set to open on January 4th, 1895. On December 26th, 1894 – just a few short days before opening night – the starlet decided that her show needed a new poster to publicize the play. Something dazzling. Something that would leave Paris speechless.

She turned to the manager of a Parisian printing firm for a new poster, pronto. Given the short notice, and the fact that Bernhardt approached the firm in the middle of the Christmas break, Maurice was short on options for the commission. In desperation, he turned to Mucha – truly the only option at hand – and begged him to take on the job. Ever the flexible type, Mucha agreed. And, in doing so, a true collaboration between two legendary artists was born.

The success of Mucha and Bernhardt’s eventual career-long collaboration is likely because the two saw eye-to-eye on Sarah’s talent.

Alphonse Mucha, Poster for ’Gismonda’ (1894). Image via muchafoundation.org.

In other words, Mucha was a fan. In creating the poster for Gismonda, he relied on his personal knowledge of the play itself, as well as his fascination with how Bernhardt depicted the title role. The result? A stunningly ethereal piece that focused the viewer of the poster on the actress herself, rather than on fussy knickknacks in the background. The poster was truly a spotlight on Sarah, in all her glory – and Sarah loved it.

Thus, the two kicked off a mutually beneficial partnership. Bernhardt became Mucha’s artistic muse and mentor in the industry. They also became very good friends. Each seemed impressed by the other’s commitment to creativity, and fervent refusal to be fenced in by artistic norms of the day. Sarah, for her part, pushed the boundaries of Parisian theater by lobbying for politically impactful roles. Mucha, on his end, blazed a trail as a high-end artist for the lower strata of society.

Much of the work Mucha did for Sarah was accessible to the everyday Parisian, because her giant posters were displayed on the street. And, he created many posters of Bernhardt in her various roles throughout the remainder of her career. Because Mucha continued to make Bernhardt the star of each new poster, his work served to elevate her career to even greater heights. In this way, Bernhardt was able to exploit her own image and likeness to increase her status as a public figure – and was one of the first known celebrities to ever do so.

The upside for Mucha was that, because of his work that featured Sarah, he became higher-in-demand as an artist for other jobs. Mucha became more famous and earned more money because he painted someone famous.

Collaboration v. Exploitation

Mucha’s portrayals of Sarah Bernhardt in his artwork were clearly a collaboration. But, using a celebrity’s image in a work of art does bring forth a question: when can an artist legally make use of a person’s image or likeness in a work of art, if use of that image increases the economic value of the work itself?

Modern Legal Framework & Application

To answer this question, two rights come into play. Both come from state, rather than federal law, and are mostly understood through case law.

The first right is called the right of privacy. This means is that private people have the right to prevent the public disclosure of their name and likeness by others. For example, if a company started using a private person’s face as the logo for a brand of salad dressing, that person could bring an action against that company claiming the right of privacy.

The second right, which sounds similar, but functions very differently, is called the right of publicity. That right means that a person has the right to exploit her own image and likeness for her own economic gain. Using the salad dressing example, this is why “Newman’s Own” salad dressing uses his face on the label. His company profits from the use of his public image on its products. The right belongs to Newman’s heirs, because the value of his image is the fruit of his own hard work as a famous actor. (Confusingly, what is referred to as the right of privacy in New York is, in fact, the right of publicity).

Sometimes, the aforementioned rules change if, instead of, as in the example, an advertiser using the celebrity’s image, the person using the celebrity’s image is an artist creating a work of art.

Some courts have held that any work created by an artist, even if it uses a celebrity’s image, is a form of free expression. The First Amendment protects free speech. Included in the many categories of free speech is art – it’s speech, even if it doesn’t make noise.

Courts that have broadly interpreted the First Amendment free speech protection in cases where an artist uses a celebrity’s image in their art have generally permitted it. According to these courts, if artist’s use of the celebrity image is a form of free speech, it is allowed. However, the application of this principle is not as straightforward as it might appear. While some courts have given artists broad discretion under the First Amendment to use celebrities in their works, other courts have sided with celebrity defendants, under the theory that the artist’s work violates the celebrity’s right of publicity.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jul 21, 2023 |

Leila has been recognized by Chambers & Partners for her work in art and cultural property law. Image via Chambers & Partners.

Amineddoleh & Assoc., LLC is proud to announce that our firm’s founder has been listed for the second consecutive year by Chambers & Partners in the latest edition of its High Net Worth Guide for her accomplishments in Art and Cultural Property Law.

Chambers indicated that Leila “is very active in this space and in the litigation area. She has a lot of expertise in the cultural property space. . . a great person in this area.” A source for Chambers went on to say, “She impresses me. She is very practically minded and has a great courtroom manner.”

We are pleased to see our founder recognized in the 2023 HNW Guide rankings for the second consecutive year. These rankings reflect not only the quality of the services our firm provides for our clients, but also our team’s fundamental commitment to providing the highest level of service to our clients.

We extend our sincerest thanks to our clients and colleagues for their confidence in our firm and in recognition of our founder’s work and expertise.

Congrats Leila!

View the ranking below:

Amineddoleh & Assoc., LLC is a premier art law practice based in NYC that advises domestic and international collectors, art dealers, galleries, artists, museums and other cultural institutions.

Our founder, Leila Amineddoleh, has recently been featured in New York Metro Super Lawyers Magazine, alongside other leaders in her field. Leila was chosen for the piece as a top-rated intellectual property, art, and cultural heritage lawyer well-known in the industry for getting the job done right. This means advocating both for her clients, and for the art and cultural heritage at issue.

Our founder, Leila Amineddoleh, has recently been featured in New York Metro Super Lawyers Magazine, alongside other leaders in her field. Leila was chosen for the piece as a top-rated intellectual property, art, and cultural heritage lawyer well-known in the industry for getting the job done right. This means advocating both for her clients, and for the art and cultural heritage at issue.