by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 31, 2023 |

Good news, thrill-seekers! Here at Amineddoleh & Assoc., not only do we provide exquisite legal services for our clients, we also know where to find a good, real-life scare. Our secret? Follow the haunted art!

Read on for our recap of our firm’s top haunted art-themed blog posts. Then, book a ticket to see the haunted art in-person. No tricks here, each destination is a true, Halloween treat.

Witch Way to the Party?

In this recent blog post, our firm traveled to Asheville, NC to get a glimpse at America’s Largest Home – and one of the most haunted. Click the link for all the details on this spooky mansion, including its most famous ghost-in-residence. Not only that, this historic home has a strange room known as the Halloween Room for visitors to experience, plus its own secret connection to protecting American art from Nazi air-raids in WWII. As if that weren’t enough to encourage a click, this post also has dazzling photos of Asheville’s gorgeous fall foliage.

Biltmore House in Autumn. Image via R.L. Terry at Wikimedia Commons.

The Ghoulishly Gory Frescos in Rome’s Santo Stefano Rotondo

Ever see art so gory it incites a physical response? Click here for more info on this real-life syndrome, known as Stendhal Syndrome, in which grotesque art and cultural heritage causes viewers to have palpitations of the heart. For those wanting to experience the syndrome in real-life, look no further than Santo Stefano Rotondo in Rome. While most tourists on a Roman holiday select beautiful frescos at the Vatican, those who venture to Santo Stefano will see a different sort of religious art. Go for the scenes of torture, stay for the bloody depictions of senseless violence. Plan to go before lunch, or else risk spilling the contents of your own stomach at the foot of these cultural works.

Gory frescoes covering the walls of the church. Image courtesy of Leila Amineddoleh, used with permission.

Cursed Art, from Statues to Paintings

Anglophiles, unite! The National Gallery in London is home to one of the most famous paintings in the world. However, this work is not famous for its artistic qualities (though they are divine). Rather, The Rokeby Venus is better-known for its ability to cause viewers to lose their minds. Click here to read all about this painting’s astonishing – and potentially cursed – provenance. The strange stories behind The Rokeby Venus illustrate how all aspects of a work’s life – including whether or not it is cursed – create its provenance. No matter what your opinion is of The Rokeby Venus’ alleged curse, the documented history of strange occurrences attributed to its ownership has become an important part of the work’s provenance.

The slashed Rokeby Venus. Image via artinsociety.com.

Haunted Happenings: The Law of Ghosts and Home Sales

If the average Airbnb isn’t scary enough this season, consider visiting a house that’s actually haunted. More and more people are reporting ghosts in domestic settings – and not always friendly ones. Trouble ensues when the place the ghost calls home is up for sale. Lawyers may be faced with the question: is a ghostly presence a condition that must be disclosed prior to sale? Would a reasonable family purchase a house that comes with a frightening ghost? Read more here to discover the actual laws that govern when a family’s new home comes with an unexpected side of ghost.

Famous ghost photograph of the Brown Lady of Raynham Hall, originally taken for Country Life (first published in December 1936).

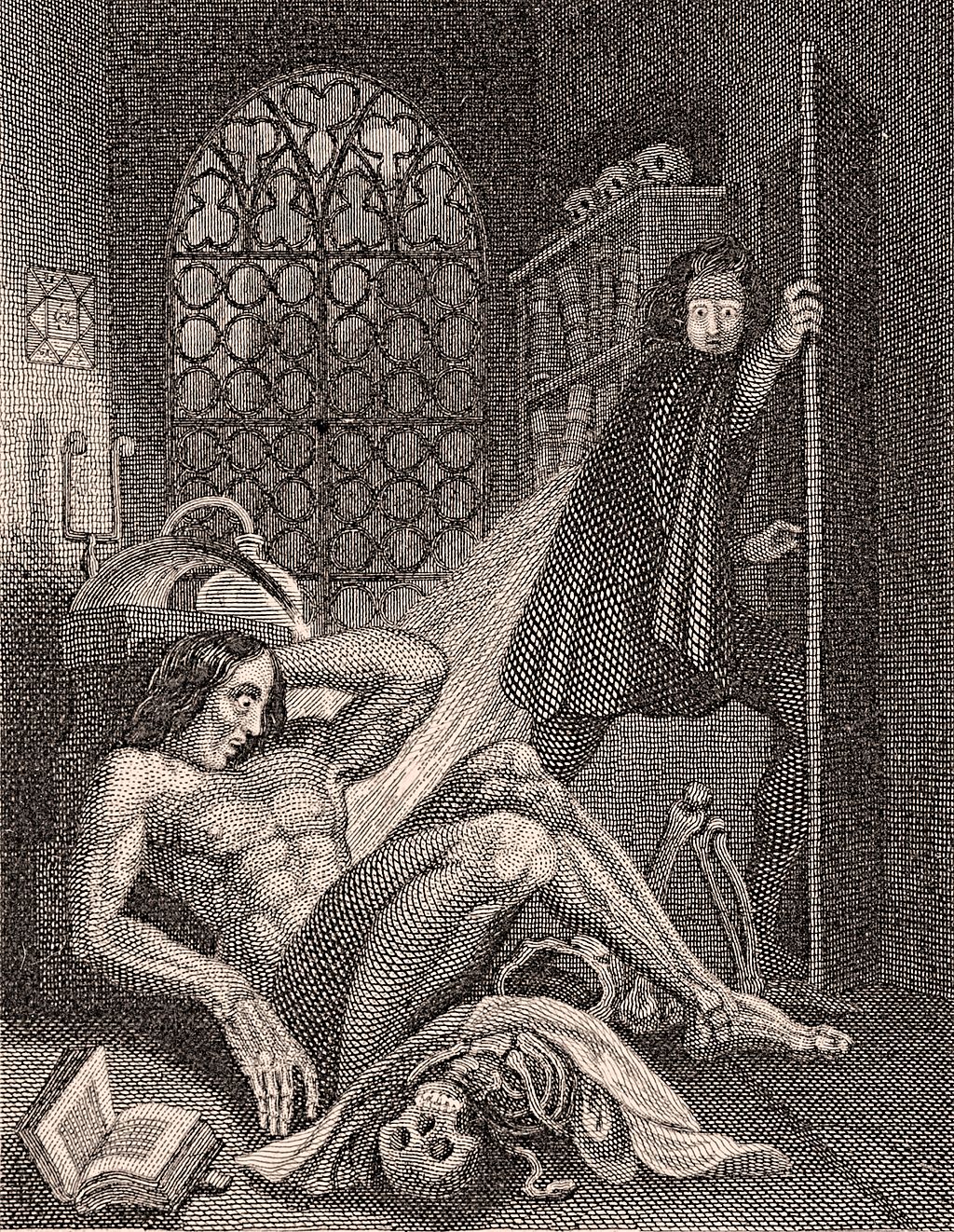

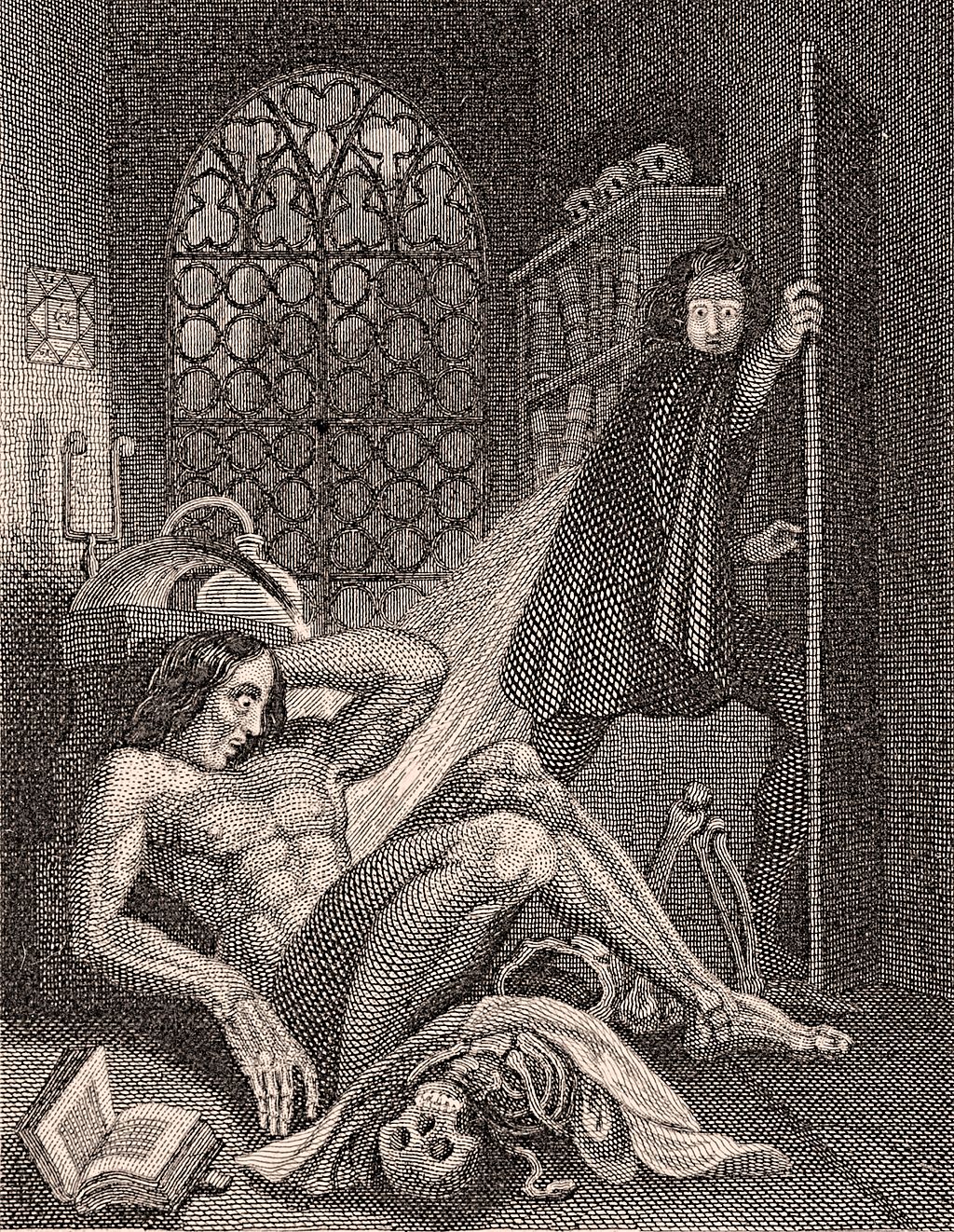

Horrifying Provenance of Monster Manuscripts

This post provides two monstrous holiday destinations in one spooky swoop: ties to Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein can be found in both New York City and Oxford, England. Online versions of Shelley’s copious notes and edits for the story can be found on The Shelley-Godwin Archive’s website through the New York Public Library. To pay a visit to the originals, travel to Oxford, where the original transcript are held as part of the Abinger Collection in the Bodleian Library. If that weren’t reason enough to visit Oxford this time of year, stop by Christ Church College for the Harry Potter-esque tour of the storied grounds. Glimpse the inspiration for the wizarding world’s tall towers and cavernous halls on the college campus. Who knows – wizards also might be walking the grounds, masked in their muggle clothes.

Illustration from the frontispiece of the 1831 revised edition of Frankenstein, published by Colburn and Bentley, London 1831.

The Cat’s Meow: Feline Art Lovers

Word on the street is that the husband of our firm’s founder is dressing as a cat for the second consecutive year this Halloween. While we can neither confirm nor deny the Halloween costumes of our firm’s families (or whether or not, in fact, the members of those families were given the freedom to select their own costumes, or if they were selected for them by their young daughters), click here for a post inspired by our culture’s love for cats in art. Thinking of dressing as a cat this year? As our founder’s husband may say, ‘tis the season!

On behalf of Amineddoleh & Associates, we wish you a safe and Happy Halloween this year!

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 26, 2023 |

Congratulations to our firm’s founder, Leila Amineddoleh, who successfully chaired the 15th Annual NYCLA Art Law Institute: New Insights in Art Law. This annual conference is one of the most highly-anticipated and innovative events of the year.

Peak fall foliage in NYC’s Central Park, just in time for the Conference. Image via Central Park Conservatory.

This year’s was no exception. The two-day event highlighted leading experts and voices in the our industry. Read below to get a glimpse of how panelists dove into the hottest topics facing artists and lawyers today – they dove into a wide array of topics, including evolving issues in the art market, art and cultural heritage law, and intellectual property.

New Developments, Dispute Resolution, & Art World Conflicts of Interest

Day 1 opened with a smash-hit panel. The panel, featuring Paul Cossu, Adrienne R. Fields, and Claudia Quinones, tackled new developments in art law and intellectual property. One highlight from this panel was the intersection of AI-created art and copyright law. A takeaway was that the U.S. Copyright Office tends to make decisions related to AI-created art based on whether AI was used merely as a tool, or whether AI was the true author.

Next, Gabrielle C. Wilson moderated a fascinating panel on resolving art disputes. The panel pondered the critical considerations and alternatives when resolving art disputes. This panel presented attendees with multiple, practical paths to use when dealing with these controversies. In some situations, art attorneys may find greater success by encouraging negotiation between parties, rather than pursuing litigation. As a whole, this second panel was a good reminder for art lawyers to continue to lean on their specific expertise in the art world to help both side achieve a just and equitable solution.

Finally, Katherine Wilson-Milne moderated a panel on art world conflicts of interest. The panel explored ways to approach these conflicts, including some suggestions for innovative paths forward. This panel encouraged participants to broaden their perception as to where art world conflicts may come from in subsequent years. With so many aspects of the cultural, financial, and political climate in flux, the art industry is being directly and indirectly impacted. It is essential for attorneys to be aware of new developments in art world conflicts of interest, and ways to best address them as they arise.

Title and Authenticity, Broken Promises, & Artist Residences

Day 2 narrowed the Conference’s focus even more precisely. The day started off with our firm’s own Yelena Ambartsumian’s presentation with Claudia Quinones. The two gave thoughtful insight and wisdom on issues surrounding title and authenticity. One highlight from Claudia’s portion included the latest developments in Nazi-looted artwork. She drew attention to the most essential cases to watch in the coming months, and provided great detail as to the specific laws at issue in each case.

Yelena then dove into powerful issues regarding cultural heritage. She brought specific attention to Armenian cultural heritage, and the current risk for destruction of such treasures. Yelena also explained the legal paths the Republic of Armenia has taken to protect their cultural heritage, due to a lack of UNESCO involvement. She also gave phenomenal insight into the hot top of authenticity issues. One takeaway from that aspect of her presentation is that, if there are reasons to be skeptical about the authenticity of a work of art, it is a good idea for the attorney to explore those suspicions!

Next up, our founder Leila moderated a fascinating panel on the enforceability of promised gifts and what happens when circumstances change. The length of time between the time the gift was made, and the time the gift is executed, was a major theme in this panel. The panel also parsed through the diverse scenarios that arise when receiving monetary gifts versus physical collections of art. In terms of physical artwork, the cost of conservation was also highlighted as an important factor in whether or not a museum or institution is even able to properly receive a certain gift. This point is especially poignant in the industry’s current climate, as costs of conservation continue to rise alongside other financial needs of leading institutions.

Melissa Passman wrapped up the day by moderating the final panel of the Conference. This closing panel explored artist residence issues, and how to navigate founder and participant relationships. One takeaway was that the resources made available to artists in these relationships tend to drive the residency as a whole. As a result, it’s important for attorneys involved to be aware of the specialized spaces and studios that may be necessary. Otherwise, it would be impossible for the artists to work and fulfill the terms of their residencies. Another takeaway was that tax laws tend to dictate what non-profit organizations are able to accomplish in these relationships. Because this could complicate artist payment in residencies, it is necessary for lawyers working with these clients to be well-aware of tax obligations, and to make that a driving factor in negotiating agreements.

Another great year!

In all, attendees experienced two action-packed days of practical advice and innovative guidance. Our firm commends all of the presenters for their hard work and fascinating presentations. We look forward to this conference each year, and this year’s was truly a celebration of the best, boldest, and brightest minds in our ever-evolving field.

Let the record stand that peak fall foliage in Central Park has its perks, but the real highlight of October in NYC is the Annual Art Law Institute.

P.S. Missed the Conference? Get in touch with NYCLA here to purchase the recording when it is released.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 18, 2023 |

Asheville, NC is where tourists in October find a plethora of autumnal sights, including phantom ones. Not only is it peak-leaf season in the Blue Ridge, it’s also peak-ghost season at Biltmore Estate.

Biltmore House in Autumn. Image courtesy of R.L. Terry via Wikimedia Commons.

Biltmore House

Biltmore Estate, home to what is considered to be America’s largest residence, sits amidst the stunning grounds designed by famed landscaper Fredrick Law Olmstead. The curated gardens and rolling hills are the perfect backdrop for the home itself, which is truly a work of art. The home is an enormous, stately French Renaissance mansion designed by Richard Morris Hunt (New Yorkers will recognize Hunt as the genius behind the pedestal of the Statute of Liberty and the façade of the Metropolitan Museum of Art). Hunt outdid himself at Biltmore in the number of rooms behind its the grand exterior. No fewer than sixty-five fireplaces, thirty-four bedrooms, forty-three bathrooms, and one indoor pool can be found inside.

Hunt also made sure to create special spots for the family-in-residence to privately retreat. Specifically, for the man of the house, Mr. George Vanderbilt, Hunt inserted a large, luxurious library. This grandiose space housed 10,000 tomes, which George likely pretended to have read. There were many lively distractions on-tap at Biltmore, which may have prevented him from really digging into the books (these felicitous diversions will be explained below).

George’s Library at Biltmore House

Whether or not George actually read any of the books, the library was a favorite retreat for him. In modern parlance, it may be referred to as his “man-cave.” The library today feels a bit spooky, and with good reason. George’s ghost is reported to visit the room with alarming frequency.

Library at Biltmore House. Image courtesy of Warren LeMay via Wikimedia Commons.

Before George died his untimely death in 1914 from complications from illness (not COVID), he was known to take his leave in the library when he heard a thunderstorm approach. His ghost seems to have kept up the habit. When late-summer and autumn storm clouds gather over the Blue Ridge, it’s a safe bet George’s ghost is high-tailing it to his sacred library. Who knew ghosts were afraid of thunder and lightening? It’s a shame thundershirts only come in “living dog”-sizes.

George’s ghost is not the only paranormal presence to haunt the historic halls of Biltmore. Remember the raucous fun this post alluded to earlier? Biltmore was famous for throwing outrageous parties in its prime. With each party, the national press had a field day. It’s hard to detail what happened at these soirées without disclosing embarrassing information about the over-served guests. Suffice it to say that these get-togethers put Gatsby’s parties to shame.

The guests so enjoyed themselves at Biltmore parties in life, that many have returned posthumously to keep the fun going. Modern-day guests report hearing clinking glasses, bits of dance music, and glittering laughter in the halls. Ghosts getting handsy with their ghoul-friends? Sounds likely.

Halloween Room at Biltmore House

Biltmore contains another spooky secret, apart from the ghosts. The creepy and mysterious Halloween Room is aptly named for this time of year. It’s a room in the basement that regularly creeps out modern-day guests. A dark, damp tunnel opens into a dimly lit, cavernous room. Adorning the walls are not the luxurious fabrics and intricate tapestries seen upstairs. Down below, the walls are covered in murals of black cats, witches, and gross-looking bats.

Halloween Room at Biltmore House. Image courtesy of Warren LeMay via Wikimedia Commons.

For years, no one – not even the living heirs of the Vanderbilt and Cecil families – knew where these painted scenes came from. The room was simply called the Halloween Room, because it was assumed that the creepy paintings were leftover decorations from a Halloween party. An autobiography of a local man revealed the truth and solved the mystery: they were leftover decorations, but the party wasn’t for Halloween – it was for New Year’s!

This new source gave all the details. On December 30th, 1925, the theme for Night One of the New Year’s festivities was “vaudeville.” Evidently, vaudeville comedic acts and European cabarets were all the rage in Manhattan. The idea was to bring a piece of the mystery and glamour down South.

What resulted was a truly legendary bash – the Charleston Daily Herald reported that over one hundred guests attended, and partied either until they dropped, or till dawn (whichever came first). One guest went on the record and called it “The best party I’ve ever attended.” If that’s the case, no wonder he and other ghosts return to Biltmore. The living dead are still killin’ it on the dance floor in the Halloween Room (but no one was actually murdered there).

Music Room at Biltmore House

As if ghosts and creepy bat paintings weren’t enough, Biltmore houses an even more spectacular secret. Modern-day tourists learn this secret back on the first floor of the home, in the Music Room. It’s here that the National Gallery of Art hid the nation’s artistic treasures during WWII.

Music Room at Biltmore House. Image courtesy of Warren LeMay via Wikimedia Commons.

Fearing a Nazi air-raid attack on the nation’s capital, David Finley – then director of the National Gallery of Art – called Edith Vanderbilt to ask a favor. Finley had been a guest at Biltmore (lucky him!) and recalled both its remote location and fireproof construction features. This winning combo made it the perfect hideaway for some of the most precious works of art in the United States. Botticelli’s The Adoration of the Magi and Rembrandt’s Self-portrait were among the sixty-two paintings and sculptures tucked neatly behind steel-enforced doors.

Guests at Biltmore in 1942 had no idea that they were sleeping under the same roof as the nation’s most valuable pieces of art. It was only after the war that the secret stash at Biltmore was made public knowledge.

Biltmore House and grounds. Image courtesy of Don Sniegowski via Wikimedia Commons.

The Story Continues at Biltmore Estate

To learn more about Biltmore House, its secrets, and all of its haunted happenings, visit Biltmore Estate in-person this season. Go for the peak fall foliage and stay for the hard-partying ghosts. There’s even a famous winery on-site – and we hear the Boo-ze is free-flowing.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 17, 2023 |

Wildfires blazed around the world this past summer with alarming intensity. The world is still feeling the effects of gigantic fires and toxic wildfire smoke. Experts continue to work to understand the impacts of these massive fires, particularly for areas that suffered multiple fires. Further complicating matters, many of these sites relied on tourist dollars for their economy. This makes the re-opening of sites (such as West Maui and specified areas on the Hawaiian west coast) fraught for local communities. Residents and government officials alike strive to balance welcoming tourists with a smile and processing their own grief and loss.

Hawaii was not the only place that suffered from wildfires. Greece, Croatia, Italy, Canada and Algeria all faced massive wildfires that obliterated homes, destroyed nature reserves, and threatened precious cultural heritage. In July, fires in Italy destroyed cultural heritage in Sicily’s Santa Maria de Gesù church. A wooden statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the remains of St. Benedict the Moor were both completely destroyed. That same month, additional fires on Spain’s Canary Islands forced evacuations of nearly 30,000 people, listed as two of UNESCO’s World Heritage Sites. With so much art, architecture, nature reserves, and other pieces of international heritage in danger, it’s almost as if the wildfires were specifically targeting culturally protected areas.

Wildfire burning in northern Greece. Image via Associated Press

Where did these fires coming from? Some say that unusually high temperatures and strong winds literally fanned the flames of some of the worst wildfires seen in decades. In addition to the devastating loss of lives and livelihood, vulnerable pieces of cultural heritage were severely damaged.

Now that the fires are no longer burning, cultural heritage experts around the world are able to identify scorched areas and initiate restoration efforts. Experts also pose this question: how to prevent such destruction by wildfire in the future? Especially when most of the world seems to take an ad hoc approach to cultural heritage restoration following natural disaster?

Greece

One of the hardest-hit areas was Greece. In August, Europe’s biggest wildfire in a century burned in northern Greece.

The fire covered an area larger than New York City, spanning 312 square miles. (For reference, New York City’s solid ground measures 302.6 square miles). Flames from this fire in northern Greece – primarily covering the regions of Evros, Rodopi, Alexandropoulis, Dadia, and northwestern Athens – proved devastating. The flames eradicated housing, farmland, and most of a national forest. In Evros, many took part in forced evacuations but, tragically, many lives were lost to the fires.

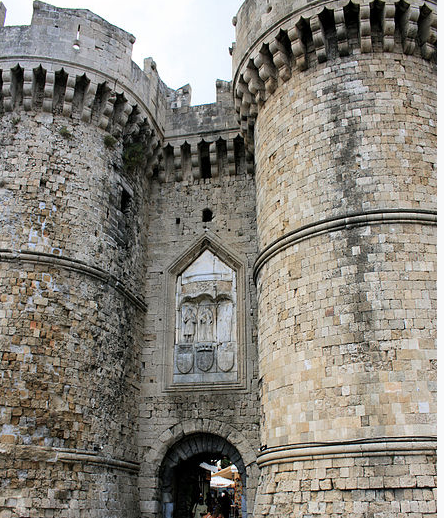

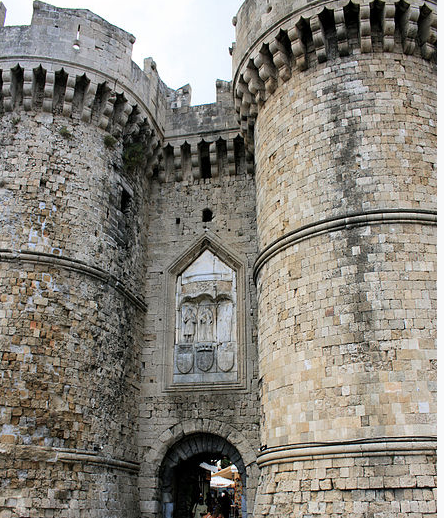

In early August, shocking damage occurred on the Grecian island of Rhodes. Satellite images showed Rhodes as a black scar of extensive damage. Evacuations in response to the flames forced thousands of residents to flee their homes and tourists to abandon their accommodations. The evacuations also prevented tourists from visiting cultural heritage hotspots that the island is known for. Namely, its legendary medieval village – a storied and mysterious acropolis built by crusaders within 4-km-long medieval stone walls.

Side-by-side aerial photos of Rhodes, Greece takein in 2019 (left) and 2023 (right). Image via BBC News.

From the beginning, this medieval town has been imbued with legends and dreams of glory. According to the island’s history, Rhodes was transformed into a fortified city by the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem in 1309. The Knights’ occupation was so strong, in fact, that they held the island until 1523 – surviving several takeover attempts by Turkish and Egyptian conquerors.

Military prowess aside, the Knights outdid themselves in terms of city planning. Once on the island, rather than destroying the “ancient core” of the place (which was a perfect grid – the product of 408 B.C., Hippodamian-style city planning), the Knights incorporated their plans for a fortified center as an extension of the ancient design. They further divided the town into a northern quarter, called the “Chateau,” and a southern quarter, called the “Ville.” The Chateau was where the Knights would hang out in their personal residences. They also made sure to stop by the palace of the Grand Master of the Order, which was bigger and fancier than their own abodes. Additionally (and likely for their own convenience), the Knights also made sure that all of the administrative buildings, hospital, and cathedral were located in the northern end. The Ville, in contrast, housed the laity. It’s also where the synagogues and other churches were constructed, as well as the noisy (and predictably odorous) public street market.

Medieval City of Rhodes. Image by Olbertz via Wikipedia.com.

When the Knights constructed these buildings, they went all-out in terms of style. Gothic and Renaissance designs, with a hint of Ottoman influences and a touch of Byzantine detail, manifested in a sensational conglomeration of art and architecture. Some of the buildings originally constructed as churches were later converted to mosques. Of the sacred spaces that remained churches, Agia Triada (the Holy Trinity), Agios Athanasios (St. Athanasius), Agia Alkaterini (St. Catherine), and Panagia tou Kastrou (the Virgin of the Castle), house gorgeous pieces of art and cultural heritage. The church of Agia Triada, for example, boasts stunning, original frescos. Sections of the fresco depict scenes from Ezekiel’s prophetic visions in the Bible. Other portions illustrate powerful images of Jesus’s Crucifixion on the Cross. And those frescos only scratch the surface in any tourist’s quest to discover the cultural heritage on this illustrious island.

Thankfully, the fires on Rhodes were eventually contained. Damage reports following the fires in Greece allowed cultural heritage to assess where restoration efforts would be needed. Inspections by the Climate Crisis and Civil Protection Ministry teams revealed the status of various architectural structures on-site. On Rhodes, six buildings were been designated by officials as unsafe for use. Twenty-two additional buildings were declared temporarily unfit, and seventeen others have been flagged as needing minor repairs.

The worst damage on Rhodes seems to have occurred in the local areas containing homes, hotels, businesses, and nature reserves. In fact, more than fifty homes, several popular resorts, and over 50,000 olive trees – a source of income for locals – were completely destroyed. Religious sanctuaries also suffered. The Monastery of Panagia Ipseni, in particular, became a verifiable inferno. The monastery’s olive orchards, vineyards, and religious icon workshop (all of which provided additional income for the monastery) were destroyed by the fire. The nuns – thankfully – were spared, yet had to endure watching their home erupt in flames, and their beautiful mosaic courtyard disappear under a layer of soot and ash.

However, the medieval city of Rhodes emerged relatively unscathed – possibly due to location and sheer luck. Even so, it is essential to acknowledge that, for Rhodes’ cultural heritage, escaping total destruction by wildfire was a very narrow victory. Moreover, even minor, “cosmetic” damage to ancient structures by wildfire smoke and extreme temperatures causes deterioration. The charred buildings, such as those seen in Lindos, indicate extensive damage to architecture. Extreme elements threaten to accelerate natural deterioration of delicate art within the medieval city. This alone poses increased dangers for those wishing to preserve Rhodes’ storied history. Restoration and preservation work must be given funding when rebuilding the city from the ashes in order to maintain Rhodes as a cultural heritage destination. Additionally, Grecian officials should consider enacting proactive measures geared toward cultural heritage, as well as putting in place orchestrated fire response protocols. Proactive preservation and planned response teams may save the day if this delicate art and architecture is threatened by natural disaster again.

Croatia

The Dubrovnik Walls in Croatia. Image via earthtrekkers.com.

Croatia’s stunning city of Dubrovnik marks a second European medieval town that narrowly escaped complete destruction of cultural heritage by wildfire this summer. Those lucky enough to have visited Croatia known that Dubrovnik houses vast artistic and architectural treasures. The Old City of Dubrovnik, referred to as the ‘Pearl of the Adriatic’, is listed as one of UNESCO’s World Heritage Sites. Dubrovnik emerged as a powerful city on the Dalmatian coast in the 13th century. The resulting influx of financial wealth produced a city that is a true jewel of art and artistry: Dubrovnik acts as guardian for an array of stunning churches, monasteries, palaces, and fountains. Each exquisite work of architecture demonstrates a celebration of Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque artistic styles.

Last summer, fires in Croatia spread just south of the ancient city. Firefighters bravely fought to contain the fire, as an additional concern was that the wildfires would set off aircraft and landmines leftover from war in the 1990s. Deployment of the explosives would have posed even greater danger to the city and its beautiful cultural heritage. Fortunately, the southerly winds shifted and, with the aid of emergency personnel on the ground, Croatians were able to protect Dubrovnik’s residents and cultural heritage from damage.

Hawaii

The wildfires on Maui, Hawaii came as a shock to Americans – and were heartbreakingly deadly. 97 people were confirmed deceased, many of them children. In light of this, it is imperative to point out that the loss of cultural heritage is not the worst outcome of wildfire. Loss of human lives is the greatest tragedy; in events of wildfire and all other forms of natural disaster, loss of lives calls for our upmost recognition and respect.

The following discussion on the implications of damage done to Hawaii’s cultural heritage in the wake of the same fire should by no means overshadow the lives lost. Rather, it is intended to bring awareness to the delicacy of cultural heritage on the island, in the hopes that, by doing so, we may greater protect it in the future.

Lahaina, on the island of Maui, maintains an important place in the history of Hawaii. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the town rose to prominence as a whaling city in the mid-1800s. Interestingly, Lahaina was also the location of a printing press that produced the first-ever newspaper printed in the Hawaiian language. The four-page weekly paper, printed on Valentine’s Day, 1834, was called “Ka Lama Hawaii.”

Missionaries that arrived in the 1820s built Western-style architecture, including the Baldwin Home. The home was built by Rev. Ephraim Spaulding in 1834 – the same year as the Ka Lama Hawaii’s debut publication. Rev. Spaulding later returned to Massachusetts, and then lent the house to Rev. Dwight Baldwin (for whom the home is now named). Why Rev. Spaulding chose to live in the snowy echelons of Massachusetts, as opposed to the gorgeous views of Lahaina, is anyone’s guess. Regardless, the Baldwin House has since been converted into a museum, and is believed the be the oldest-surviving residence on Maui. A visit to the museum is a lesson in missionary life in an 1820s Hawaiian village – visitors can expect a tour of the house and grounds, as well as a peek into the vibrant, busy lift of the Baldwins’. The family knew how to throw a good party, and often received members of Hawaii’s royal court. For Lahainans in the 1840s, it was the place to see-and-be-seen.

The Baldwin Home on Lahaina in Maui, Hawaii. Image via Lahaina Restoration Foundation.

Unfortunately, the Baldwin Home is one of many buildings that suffered extensive damage in the fire. The House had a wooden roof, which was completely burned by flames. The Baldwin Home Museum’s director, Theo Morrison, stated (shortly after the fire) that he suspected “the entire building was gutted.” This was later confirmed.

As more reports following the fire on Maui were released, damage to other precious cultural heritage sites on the island was to be expected. Reports – most tellingly, those from Native Hawaiians – revealed that cultural landmarks, art, and architecture crucial to the Hawaiian cultural narrative were destroyed. This includes sites on Lahaina were the first Hawaiian Constitution during the kingdom era was written in the 1800s, and an ancient fish pond where Hawaiian monarchs were known to take their rest and leisure.

Although Maui is often touted as a tourist site, for Native Hawaiians, it has been long-known as the heart of their storied history. In this light, the impact of cultural heritage lost by the wildfires points to the power and enduring influence of irreplaceable art, artifacts, and historic sites. The art community must look to ways to proactively prevent vulnerable pieces of cultural heritage from destruction by extreme natural weather events. The reality is that damage done to treasured works of art and cultural heritage anywhere causes the world to lose crucial components of shared human history.

Who’s to Blame?

As the world continues to reflect on the summer wildfires, many seek to find a scapegoat for the destruction. Climate change, arson, and inefficient government response teams have all been blamed. However, at this stage in the world’s evolution, pointing fingers does little to solve the problem at hand. Loss of delicate art and cultural heritage by natural disaster is part of the new normal. If art is to be preserved for future generations, proactive protection measures should be the first line of defense.

The second line of defense should be an increased awareness of the importance of preserving such heritage, and a place for that awareness in planning for orchestrated response efforts.

The third line of defense? It’s a call to individual action, and it comes from Smokey.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 10, 2023 |

Our firm is delighted to announce that our founder, Leila Amineddoleh, has been listed as one of the Top 10 Most Influential Art and Cultural Property Law Lawyers in Business Today’s 2023 Lawyer Awards.

Scales of Justice. Image via Ggreidcao at Wikimedia Commons.

This honor recognizes art and cultural property lawyers who are “[m]asters of their craft.” Additionally, winners are recognized for “their exceptional understanding of this niche field, their strategic outlook, critical thinking, and impeccable negotiation skills.”

Leila was chosen as a result of her hard work in this field. Specifically, she was selected “for her deep understanding of cultural property restitution,” and the way that she “thrives at the intersection of law and art.” The award further explains that “[Leila] brings a unique touch of fervor to her work, combined with a comprehensive understanding of art law.”

Join our firm as we congratulate Leila on receiving this exclusive accolade. We are so proud of Leila and all of her hard work.

Read more about the award, and all of the other winners, here.