by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jul 13, 2020 |

Interior of Hagia Sophia, © Leila Amineddoleh

In what critics are calling a politically provocative and decisive move, Turkish President Erdogan signed a decree removing Hagia Sophia’s status as a museum to allow it to be used as a mosque again. The president of the Hellenic Republic of Greece tweeted, “The decision of the Turkish leadership to turn #HagiaSophia into a mosque is a profoundly provocative act against the international community. It brutally insults historical memory, undermines the value of tolerance, and poisons Turkey’s relations with the entire civilized world.”

Interior of Hagia Sophia, © Leila Amineddoleh

On July 10, Turkey’s highest court repealed the 1934 decision that converted Hagia Sophia from a mosque into a museum. Notably, the decree put restrictions on prayers being performed at the site. For decades, Hagia Sophia has been one of the most visited tourist attractions in Turkey. Authorities insist that the features of Hagia Sophia, a significant historical and cultural heritage site, will continue to be preserved and protected, and it will be accessible to the public in the same manner that the Blue Mosque is open to visitors of all faiths. However, the move has caused outrage around the world from cultural heritage conservationists, and critics who argue that the building is being used to stir nationalism and promote tension between religious groups. To understand the international concern over the step, it is important to understand a bit about the history of the magnificent building.

HISTORY OF ONE OF THE WORLD’S TREASURED SITES

The awe-inspiring structure has a long history and it has undergone many transformations. Prior to its construction, two churches resided on that site which were destroyed in violent riots. Hagia Sophia (meaning “Holy Wisdom”) was erected under the orders of Emperor Justinian I between 532 and 537. Designed by Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles of Greece, it contained the world’s largest interior space. Designed as a combination of Roman basilica and domed Roman central building, the central and recognizable element of the structure is a large dome modeled after the Pantheon in Rome. The original dome imploded in 558 after a number of seismic shocks, but it was rebuilt in 562 and the building was consecrated as a church. Hagia Sophia is also adorned with marble tiles, mosaics, ceramics, and glittering gold and precious and semiprecious stones. The brilliance of light flooding its 91 windows and open spaces create the impression of weightlessness and grandeur. A testament to its scale and import, it remained the world’s largest cathedral for nearly a millennium.

Interior of Hagia Sophia © Leila Amineddoleh

Over the years, Hagia Sophia was converted many times for religious purposes. First in 1204, during the Fourth Crusades, it was changed from a Christian Orthodox church to a Roman Catholic cathedral. Six decades later, it was restored to an Orthodox site. After the Fall of Constantinople (current day Istanbul) in 1453 under Mehmed the Conqueror, Ottoman rulers converted the church into a mosque. During the bloody battle for Constantinople, the Hagia Sophia was won and looted by Ottoman forces. When the Islamic forces later took control of the cathedral, they immediately converted it into a mosque. During Hagia Sophia’s time as a mosque, Islamic architectural features were added, including a minbar, four minarets and a mihram, serving as inspiration for many other Ottoman mosques. Hagia Sophia became the principal mosque of Istanbul.

In 1935, the founder of the Republic of Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk secularized and converted Hagia Sophia into a museum. After standing as a museum for the world for nearly a century, it was announced that the building will be converted into a mosque. The 1935 decision to convert Hagia Sophia into a museum was annulled by the Council of State, and the Turkish President signed a decree converting it into an operating mosque.

Not surprising, after centuries of looting and conversion, conservationists are worried about the integrity and preservation of this incredibly important cite. “Conservationists and art historians have raised concerns about what will happen to the medieval mosaics inside Hagia Sophia, which depict the Holy Family and portraits of imperial Christian emperors, which strict Muslims may demand be covered. Tour guides said that the building may be closed to tourists during prayer times, or even that parts of the building be sectioned off to non-Muslims.” It is unclear if there are currently any plans to make such adjustments, which would echo historical efforts to use Hagia Sophia as a symbol of religious supremacy. Turkish presidential spokesman, Ibrahim Kalin, stated that Hagia Sophia could function as a mosque and be open to visitors in the same way that Notre Dame and Sacre Coeur in Paris hold services and are open to tourists.

RELIGIOUS UPSET

Chora Church, © Leila Amineddoleh

Another reason for outcry over the change is that Hagia Sophia has become a symbol of secularism, a core value of the modern Turkish state since its founding. Prior to its conversion to a museum, the building served as a reminder of the centuries-long clash between Christianity and Islam. By removing its status as a secular structure, it once again becomes a symbol of strife between two of the world’s largest religions. The move to convert the building also moves the Turkish state toward a more religious leadership, as the conversion of Hagia Sophia to a mosque has been long sought after by conservative Muslins. The recent decision reflects Erdogan’s intention to stir his nationalist and religious base. A similar fate has already met the Church of the Holy Saviour in Chora, a medieval Byzantine Greek Orthodox Church. The original church on the site was built in the early 4th century, and it became incorporated within the city’s defenses (however, the majority of the current building dates to the late 11th century). In the 16th century, it was converted into a mosque and then became a museum in 1948. In November 2019, the Turkish Council of State ordered that it would be reconverted to a mosque.

The conversion of Hagia Sophia has predictably drawn criticism from many of the world’s religious leaders. Bartholomew, the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople and spiritual leader of the Eastern Orthodox Church, said the conversion of Hagia Sophia into a mosque would disappoint millions of Christians around the world and divide Muslims and Christians since it had long been a place of worship for both. During a service in the Vatican, Pope Francis lamented the change, stating he was “very saddened,” and later stood in silence for several minutes.

Mosaic in Hagia Sophia © Leila Amineddoleh

In response, Turkish authorities provided comments about this monumental decision. “Hagia Sophia’s status is not an international matter but a matter of national sovereignty for Turkey,” Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu said. Turkish Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hami Aksoy stated, “Hagia Sophia, like all cultural assets on our lands, is the property of Turkey.” However, that is not how the world views the monument, which holds significance for many religious sects and nations. It has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1985. UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) is a specialized agency of the United Nations. The agency described that it “deeply regrets” the decision, which was made without prior consultation. In a press release, UNESCO’s Director-General Audrey Azoulay said that “Hagia Sophia is an architectural masterpiece and a unique testimony to interactions between Europe and Asia over the centuries. Its status as a museum reflects the universal nature of its heritage, and makes it a powerful symbol for dialogue.” The statement went on to state that any countries wishing to make changes to UNESCO World Heritage Sites are required to consult UNESCO so that committee members from other nations can raises concerns affecting their own heritage. Lastly, UNESCO asked that Turkey immediately initiate a dialogue to discuss its planned changes for Hagia Sophia.

One such nation with significant ties to the site is Greece, which sees itself as the cultural heir to the Byzantine Empire, and which has emphatically denounced the conversion as a breach to Hagia Sophia’s status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Lina Mendoni, the Greek Minister of Culture, issued a statement in which she decried the decision as a “direct challenge to the entire civilized world,” and stated that “President Erdogan has chosen for Turkey its cultural isolation.” The statement is bolstered by a tweet (see above) from the Greek President admonishing the decision along similar grounds.

As tensions build, fans of Hagia Sophia will find solace in learning that at least one of the museum’s most distinctive characteristics will not be changed. It was announced that Gli, a cat who was born in the Hagia Sophia in 2004 and who has since been appointed as one of its guards (maintaining an Instagram account with over 32K followers), will continue his service even after the conversion.

The conversion of the museum into a mosque is a prime example of the politicizing of cultural heritage to advance the agenda of a political leader.

TIMELINE

Interior of Hagia Sophia © Leila Amineddoleh

Orthodox Church 537-1204

Catholic Church 1204-1261

Orthodox Church 1261-1453

Mosque 1453-1934

Museum 1935-2020

Mosque 2020

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jul 6, 2020 |

Readers may recall from a previous blog post that Facebook Marketplace has become the subject of criticism for playing host to antiquities traffickers selling looted cultural heritage items online. Employing Facebook’s sophisticated algorithms, traffickers quickly connect with buyers receptive to purchasing plundered goods or with less experienced buyers who do not recognize the red flags associated with looted antiquities. Red flags include an origin from a conflict zone (such as Syria or Iraq), lack of provenance or export documents, and comparatively low prices in relation to the object’s scarcity or true value. Online sales have flourished after the looting of cultural heritage sites during and after the Arab Spring, and illicit trafficking of antiquities has been recently exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has left many cultural heritage sites defenseless and ripe for plunder. Antiquities as varied as scrolls, coins, and even mummified human remains are sold through online groups. More troubling is the fact that members would discuss how to illegally excavate historical sites. Some members provide tips on how to avoid law enforcement officials, while others make specific “loot to order” requests, deliberately targeting specific objects. The smuggling of Middle Eastern antiquities has been linked to terrorist groups and other crime syndicates. While physical border security may be tightened, it is more difficult to tackle online transactions.

As a result, groups like the ATHAR Project have been demanding changes. “Athar” is the Arabic word for antiquities, but the name also stands for “Antiquities Trafficking and Heritage Anthropology Research.” Co-Directors Prof. Amr Al-Azm and Katie A. Paul have dedicated the project to ascertaining relationships between the digital underworld, transnational trafficking, terrorism financing, and organized crime. The founders have spoken to media outlets to assist investigations into the issue. In response to this outcry, Facebook announced a change in policy to ban from its marketplace any “content that attempts to buy, sell, trade, donate, gift or solicit historical artifacts.” The change was made effective as of June 23, 2020.

As a result, groups like the ATHAR Project have been demanding changes. “Athar” is the Arabic word for antiquities, but the name also stands for “Antiquities Trafficking and Heritage Anthropology Research.” Co-Directors Prof. Amr Al-Azm and Katie A. Paul have dedicated the project to ascertaining relationships between the digital underworld, transnational trafficking, terrorism financing, and organized crime. The founders have spoken to media outlets to assist investigations into the issue. In response to this outcry, Facebook announced a change in policy to ban from its marketplace any “content that attempts to buy, sell, trade, donate, gift or solicit historical artifacts.” The change was made effective as of June 23, 2020.

Although the ban is an encouraging step towards the eradication of antiquities trafficking, Facebook’s decision is indicative of a larger problem facing the art market: the move to online sales spurred by developments in technology, and more recently the pandemic, has rendered the market more vulnerable to traffickers selling loot. Closing the Facebook Marketplace to “historical artifacts” is perhaps a well-intentioned gesture, but it fails to adequately address the concerns in the larger market. An expert was quoted as suggesting that Facebook should invest in specialized teams to identify and remove criminal networks at their source rather than “playing whack-a-mole with individual posts.”

As Facebook’s abdication from the marketplace evidences, commercial actors are rarely incentivized to police their salesrooms. Further, the responsibility for reclaiming stolen property falls on the work’s country of origin. Even auction houses, which often carry out due diligence procedures, have been known to allow works with questionable provenance to reach the auction floor (more on this trend below). Relying on nations to recover looted works is problematic. Nations protect their heritage, often through a cultural ministry or national museum. Unfortunately, governments do not have the resources to investigate the global art market or recover property through litigation. Increasing the number of smaller, online sales makes this already Sisyphean task all the more impossible. Some nations monitor the market and confront sellers when questionable works appear on the market. Greece notably faced claims in federal court in New York after it communicated with an auction house about a suspicious item. Fortunately, our client was victorious in defending itself against jurisdiction in the U.S.

As Facebook’s abdication from the marketplace evidences, commercial actors are rarely incentivized to police their salesrooms. Further, the responsibility for reclaiming stolen property falls on the work’s country of origin. Even auction houses, which often carry out due diligence procedures, have been known to allow works with questionable provenance to reach the auction floor (more on this trend below). Relying on nations to recover looted works is problematic. Nations protect their heritage, often through a cultural ministry or national museum. Unfortunately, governments do not have the resources to investigate the global art market or recover property through litigation. Increasing the number of smaller, online sales makes this already Sisyphean task all the more impossible. Some nations monitor the market and confront sellers when questionable works appear on the market. Greece notably faced claims in federal court in New York after it communicated with an auction house about a suspicious item. Fortunately, our client was victorious in defending itself against jurisdiction in the U.S.

On its face, banning cultural heritage items from Facebook Marketplace appears to be a responsible choice. In truth, Facebook is relegating a problem that it helped foster to nations that are already struggling to police the market. Critics of the ban argue that Facebook’s role in the illicit market makes the works more visible and easier for countries to locate. By closing its doors, Facebook has likely pushed these sales deeper into the black market, making them more difficult to track and recover. Further, Facebook indicated that it will not preserve information associated with the sale of artifacts, citing privacy concerns. This means that any information on the site will be destroyed rather than shared with countries of origin. Noting that “theft, pillage or misappropriation of” cultural property violates international law and constitutes a war crime, critics assert that social media evidence has been used by the International Criminal Court to prosecute and convict war criminals as recently as 2017. Facebook is ready to wash its hands of the market for looted antiquities, but in doing so, is neglecting the possibility of using its already established position to counteract the presence of looting on a more effective and direct basis.

The wooden sculptures, one male and one female, represent deities from the Igbo community. Copyright: Christie’s

Facebook is not alone in playing a troubling role in the illicit market. Whereas some traffickers exploit the dark recesses of the internet, others turn to the its most prominent levels in an attempt to legitimize a looted artwork. Due diligence measures have slipped during the COVID-19 pandemic, as buyers and intermediaries have been unable to inspect works personally. Recently, Christie’s was called upon by a prominent art historian to pull two Nigerian statues from a sale in Paris, believing the works were looted during civil war in the 1960s. At the very least, more information would be necessary to determine if the works had been exported illegally. Yet despite these concerns, Christie’s proceeded with the auction. Defending the sale, Christie’s maintained that there wasn’t “any suggestion that these statues were subject to improper export,” prior to the academic’s request. Unfortunately, this response side-steps an inconvenient truth that doubts about provenance may only surface once a work enters the global spotlight, as in an auction house sale. For instance, the lack of prior ownership claims may be due to the item being held in a private collection prior to sale. An official for the Nigerian National Commission for Museums and Monuments said he “was saddened” by the sale, but the country has not yet made a formal demand for repatriation. Despite the controversy, and perhaps encouraged by the lack of action by Nigeria, the piece sold for just under $240,000 (£195,000). Only time will tell whether the statues become the subject of litigation.

It is important for collectors to understand the particularities of acquiring antiquities, and it is important consult knowledgeable professionals to avoid problems. Amineddoleh & Associates has a wealth of experience addressing the challenges faced by foreign nations and private owners. Our founder has served as an expert for a number of high-profile repatriations. (She served as a cultural heritage law consultant in the return of thousands of looted artifacts to Iraq in the “Hobby Lobby” forfeiture, and as a cultural heritage law expert in matters such as the return of an Achaemenid relief to Iran, a golden coffin and mummy parts to Egypt, and a mosaic from one of Caligula’s ships to Italy.) This firm has represented museums, foreign nations, collectors, and sellers in litigations and transactional matters. Moreover, we routinely aid our clients in conducting due diligence to ensure that their purchases are legally permitted and free from encumbrance. As the pandemic continues and online cases soar, savvy purchasers must be as cautious as possible and contact legal counsel familiar with the art market’s pitfalls.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jun 19, 2020 |

Finding of the Sybilline Books and the Tomb of Numa Pompilius, ca. 1524–1525, workshop of Giulio Romano with Polidoro Caldara da Caravaggio. Bibliotheca Hertziana. Courtesy of the Getty Museum.

Like with fine art, it is important to look at the provenance of antiquities. But understanding the history of antiquities involves more than just provenance (the ownership history). It is also essential to examine the provenience (the work’s findspot). A work’s provenience includes more than where it was excavated, it describes the context in which the item was found, providing scholars with essential information about its origin, use, and importance. For instance, the same object might be understood differently if it is found at an altar than if it were found relegated to a corner. Because objects moved across ancient trade routes, their findspots are important to our understanding about exchanges between cultures. Unfortunately, when looters strip an archaeological site of its valuables, scholars lose this context and we are denied access to important knowledge. Plunder and illegal export of antiquities from around the world pose the threat of irreparable harm to mankind’s cultural heritage.

Provenience is also instrumental in resolving ownership disputes, particularly in the application of national patrimony laws. In order for a nation to demand the return of an object originating from within its borders under the National Stolen Property Act, that country must have enacted a patrimony law that vests ownership of the property to the nation. If artifacts are excavated and removed in contravention to these laws, they become stolen goods. As in all matters of theft, the party demanding the return of property (here the nation), must establish rightful ownership. This can be a very challenging task in the case of looted antiquities as a nation might not become aware of a looted item’s existence for many years, and because looted objects typically are not accompanied by paperwork attesting to their pasts.

Very often, antiquities have huge gaps in provenance because these works remain underground–both literally and figuratively–for centuries. An item kept in a tomb for centuries is never exhibited nor passed from owner to owner, and so does not develop a provenance that helps to provide clear title to the artwork. In such cases, the modern provenance (the post-excavation record) of certain antiquities may be appealing to collectors. Generally, the longer a work has been in the public eye, the lower chance a nation might claim it was looted or exported illegally.

The Vatican Museums boast one of the most impressive art and antiquities collection in the world. For the past five centuries, Laocoön and His Sons has been one of its gems, depicting nearly life-size figures from the Trojan War. Laocoön, a priest of Apollo in the city of Troy, warned his fellow Trojans against taking in the wooden horse left by the Greeks outside the city gates. Athena and Poseidon, who favored the Greeks, sent two great sea-serpents to kill Laocoön and his two sons. From the Roman point of view, the death of these innocents was crucial to the decision of Aeneas, who heeded Laocoön’s warning, to flee Troy, leading to the eventual founding of Rome.[1]

The Vatican Museums boast one of the most impressive art and antiquities collection in the world. For the past five centuries, Laocoön and His Sons has been one of its gems, depicting nearly life-size figures from the Trojan War. Laocoön, a priest of Apollo in the city of Troy, warned his fellow Trojans against taking in the wooden horse left by the Greeks outside the city gates. Athena and Poseidon, who favored the Greeks, sent two great sea-serpents to kill Laocoön and his two sons. From the Roman point of view, the death of these innocents was crucial to the decision of Aeneas, who heeded Laocoön’s warning, to flee Troy, leading to the eventual founding of Rome.[1]

Scholars categorize the work as being of the Hellenistic “Pergamene baroque,” a style that began in Greek Asia minor in the 3rd century BC (the best known work being the Pergamon Altar (circa 180-160 BC). In Hellenistic fashion, Laocoön and His Sons displays attention to the accurate depiction of movement: the three men desperately try to break free from the hold of the sinuous serpents. No matter how much they struggle, they remain tragically entangled.

Most historians believe that the marble sculpture is a copy of an earlier bronze. Due to its style and subject matter, art historians believe the original Laocoön and His Sons was sculpted around 200 BCE in Pergamon. This theory is supported by Pliny the Elder who admires the piece in Volume XXXVI of Natural History. He attributes the work to three sculptors from Rhodes, and places its location in the palace of the Emperor Titus, where it possibly remained until its modern discovery.

The statue group was found on the Esquiline Hill in Rome and immediately identified as the Laocoön as described by Pliny the Elder. The group was excavated in February 1506 in the vineyard of Felice De Fredis. At the request of Pope Julius II, Michelangelo and Giuliano da Sangallo were present at the unearthing. Sangallo’s son, only 11-years-old at the time, wrote an account about the excavation over sixty years later:

The statue group was found on the Esquiline Hill in Rome and immediately identified as the Laocoön as described by Pliny the Elder. The group was excavated in February 1506 in the vineyard of Felice De Fredis. At the request of Pope Julius II, Michelangelo and Giuliano da Sangallo were present at the unearthing. Sangallo’s son, only 11-years-old at the time, wrote an account about the excavation over sixty years later:

“The first time I was in Rome when I was very young, the Pope [Julius II] was told about the discovery of some very beautiful statues in a vineyard near Santa Maria Maggiore [on the Esquiline Hill]. The pope ordered one of his officers to run and tell Giuliano da Sangallo to go and see them. He set off immediately. Since Michelangelo Buonarroti was always to be found at our house, my father having summoned him and having assigned him the commission of the Pope’s tomb, my father wanted him to come along too. I joined up with my father and off we went. I had climbed down to where the statues were, when immediately my father said, ‘That is the Laocoon, which Pliny mentions.’ Then they dug the hole wider so that that they could pull the statue out. As soon as it was visible everyone started to draw, all the while discoursing on ancient things, chatting about the ones [ancient statues owned by the Medici] in Florence.”[2]

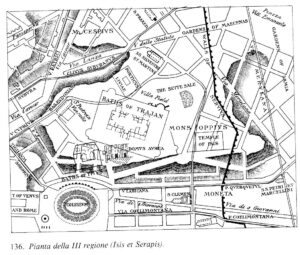

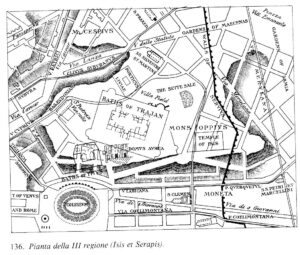

The exact spot of its finding was not clear for centuries, except for vague statements, such as “near Santa Maria Maggiore” or “near the site of the Domus Aurea.” The vineyard of Felice de Fredis, noted in the sales document to the Pope, was just inside the Servian Wall on the southern spur of the Esquiline, east of the Sette Sale (the cisterns) supplying the nearby imperial Baths of Titus and Trajan which were built over the reviled Domus Aurea of Nero. This area was once the site of the Gardens of Maecenas, where Tiberius later resided.[3] This information was ascertained from a document recording De Fredis’ purchase of the vineyard 14 months before the statue’s discovery. (De Fredis’ house survives today.)

Pope Julius II immediately acquired the group and had it displayed in the Cortile delle Statue (Courtyard of the Statutes), making it the centerpiece of the collection. A base was eventually added in 1511. The Laocoön’s discovery influenced art into the Baroque period, with Michelangelo particularly taken by the piece. The sculptural group was depicted in prints and small models, becoming famous throughout Europe. The work is widely regarded as one of mankind’s greatest artistic achievements. Countless writers have mused about its qualities, with Johann Joachim Winkelmann writing about the paradox of admiring beautiful in a depiction of death and failure. Johann Goethe wrote of the work, “A true work of art, like a work of nature, never ceases to open boundlessly before the mind. We examine, — we are impressed with it, — it produces its effect; but it can never be all comprehended, still less can its essence, its value, be expressed in words.[4]

The statue faced an uncertain future toward the end of the 18th century. In July 1798 it was taken to France in the wake of the French conquest of Italy. It was displayed when the new Musée Central des Arts, later the Musée Napoléon, opened at the Louvre in November 1800. After Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo, when much of the art plundered by France was returned, the Laocoön returned to the Vatican in January 1816.

Few pieces in existence today can match the superb provenience of Laocoön and His Sons, typically leaving antiquities collectors with limited knowledge when making a purchase. In truth, some collectors have developed a tolerance for scant information, accepting that some degree of risk will always be present in the market. In such cases, collectors rely on the information that is available, namely the work’s provenance since it reemerged into the public’s awareness. One exemplary piece with a rich provenance is a 900-year-old large black stone carving of Lokanatha from India sold through Christie’s Auction House in 2017.

Leiko Coyle with the record-breaking antiquity. Courtesy of Christie’s.

Standing nearly five feet tall and carved from a single piece of stone, the work depicts a seated Lokanatha Avalokiteshvara, the Buddhist deity embodying compassion. Lokanatha is identified by a seated Buddha set in the center of his crown and a long, blooming lotus draped over his left shoulder. The piece also features plump, youthful feet typical of portrayals of divinity and interlocking coils of hair (not unlike the serpents entangling Laocoön and his sons). Although the statue has lost both arms, a common occurrence for Buddhist statues that have survived to modernity, Lokanatha retains a striking and illuminating presence.

The work’s power is due in part to its impressive size, a trait that sets it apart from other works made during the same era. The piece is dated to the Pala Period of the 12th century, which was named for the expansive empire that then controlled what is now West Bengal in India and Bangladesh. This empire produced remarkably detailed and sophisticated works of sculpture, making pieces such as the Lokanatha highly sought after by collectors.

The physical characteristics are not the only thing that attracted bidders to this piece: it has a sterling provenance. “The most remarkable thing about this sculpture, besides its quality and sheer size, is its provenance,” says Christie’s specialist Leiko Coyle in the weeks leading up to auction.[5] Ms. Coyle worked with the consignor to successfully investigate the provenance of the exquisite piece. The work first reappeared in 1922 as the centerpiece of one of America’s first collections of Indian art, established by the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The work then entered a private European collection in 1976, where it remained for 40 years before going up for sale.

The catalog entry for the piece recounts the following information:

“It was first acquired in the year 1922 for the Boston Museum by none other than Dr. Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy (1877-1947)… In 1917, when the museum was already world famous for its rich collection of Chinese and Japanese art, it obtained a substantial assemblage of Indian art from Coomaraswamy who had begun amassing the material mostly in India under the British Raj around 1910. At the time there was no restriction in the movement of art among the various nations or from continent to continent. One of the greatest patrons and benefactors of the museum Dr. Denman Ross (1853-1935), a wealthy Bostonian and a professor of art and design at Harvard University (as well as a MFA trustee) had been steadily forming a vast private collection of art of global diversity, including India since the late 19th century... Ross and Coomaraswamy had met in London in the first decade of the 20th century and it was largely due to their cooperation that the museum had secured the famous Goloubew Collection of Indian and Persian paintings in 1914 which Coomaraswamy would publish a few years after joining the museum in 1917.”

The work’s history and public display assured buyers with a level of confidence that the statue would likely not be subject to a repatriation claim. In a market with imperfect records, this is an ideal history.In the case of the Lokanatha, that confidence translated to a sale price of $24.6 million dollars, setting a record for South Asian art.

[1] http://www.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani/en/collezioni/musei/museo-pio-clementino/Cortile-Ottagono/laocoonte.html

[2] Letter of Francesco da Sangallo, quoted in Leonard Barkan, Unearthing the Past: Archaeology and Aestheticsin the Making of Renaissance Culture (1999)

[3] https://www.ancientworldmagazine.com/articles/laocoon-suffering-trojan-priest-afterlife/

[4] Upon the Laocoon

[5] 5 minutes with… A 900-year-old Indian Pala-period statue, Christie’s (Mar. 16, 2017), https://www.christies.com/features/Leiko-Coyle-with-a-South-East-Asian-Pala-figure-8088-1.aspx.

As a result, groups like the

As a result, groups like the  As Facebook’s abdication from the marketplace evidences, commercial actors are rarely incentivized to police their salesrooms. Further, the responsibility for reclaiming stolen property falls on the work’s country of origin. Even auction houses, which often carry out due diligence procedures, have been known to allow works with questionable provenance to reach the auction floor (more on this trend below). Relying on nations to recover looted works is problematic. Nations protect their heritage, often through a cultural ministry or national museum. Unfortunately, governments do not have the resources to investigate the global art market or recover property through litigation. Increasing the number of smaller, online sales makes this already Sisyphean task all the more impossible. Some nations monitor the market and confront sellers when questionable works appear on the market. Greece notably faced claims in federal court in New York after it communicated with an auction house about a suspicious item. Fortunately,

As Facebook’s abdication from the marketplace evidences, commercial actors are rarely incentivized to police their salesrooms. Further, the responsibility for reclaiming stolen property falls on the work’s country of origin. Even auction houses, which often carry out due diligence procedures, have been known to allow works with questionable provenance to reach the auction floor (more on this trend below). Relying on nations to recover looted works is problematic. Nations protect their heritage, often through a cultural ministry or national museum. Unfortunately, governments do not have the resources to investigate the global art market or recover property through litigation. Increasing the number of smaller, online sales makes this already Sisyphean task all the more impossible. Some nations monitor the market and confront sellers when questionable works appear on the market. Greece notably faced claims in federal court in New York after it communicated with an auction house about a suspicious item. Fortunately,

The Vatican Museums boast one of the most impressive art and antiquities collection in the world. For the past five centuries, Laocoön and His Sons has been one of its gems, depicting nearly life-size figures from the Trojan War. Laocoön, a priest of Apollo in the city of Troy, warned his fellow Trojans against taking in the wooden horse left by the Greeks outside the city gates. Athena and Poseidon, who favored the Greeks, sent two great sea-serpents to kill Laocoön and his two sons. From the Roman point of view, the death of these innocents was crucial to the decision of Aeneas, who heeded Laocoön’s warning, to flee Troy, leading to the eventual founding of Rome.

The Vatican Museums boast one of the most impressive art and antiquities collection in the world. For the past five centuries, Laocoön and His Sons has been one of its gems, depicting nearly life-size figures from the Trojan War. Laocoön, a priest of Apollo in the city of Troy, warned his fellow Trojans against taking in the wooden horse left by the Greeks outside the city gates. Athena and Poseidon, who favored the Greeks, sent two great sea-serpents to kill Laocoön and his two sons. From the Roman point of view, the death of these innocents was crucial to the decision of Aeneas, who heeded Laocoön’s warning, to flee Troy, leading to the eventual founding of Rome. The statue group was found on the Esquiline Hill in Rome and immediately identified as the Laocoön as described by Pliny the Elder. The group was excavated in February 1506 in the vineyard of Felice De Fredis. At the request of Pope Julius II, Michelangelo and Giuliano da Sangallo were present at the unearthing. Sangallo’s son, only 11-years-old at the time, wrote an account about the excavation over sixty years later:

The statue group was found on the Esquiline Hill in Rome and immediately identified as the Laocoön as described by Pliny the Elder. The group was excavated in February 1506 in the vineyard of Felice De Fredis. At the request of Pope Julius II, Michelangelo and Giuliano da Sangallo were present at the unearthing. Sangallo’s son, only 11-years-old at the time, wrote an account about the excavation over sixty years later: