by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Nov 12, 2020 |

Photo from Facebook/Twitter, accessed from The Guardian

When will it stop? Spain once again made news after another botched “restoration” captured the public’s attention. Now referred to as the Potato Head of Palencia, the once smiling statue of a woman has fallen victim to “substandard” restoration. It is the most recent atrocity in a line of restorations-gone-wrong in the Iberian nation. The highly-publicized line of incidents began with the comically bad creation of the “Beast Jesus” in Borja, Spain. Shockingly, the restorer intended to restore a painting of Jesus, but created an unusual image more akin to a monkey than to Christ.

Experts in Spain are calling for stricter conservation guidelines because these seemingly comic restorations actually irreparably damage the nation’s heritage. Responding to the Palencia restoration, Spain’s Professional Association of Restorers and Conservators (ACRE) wrote on Twitter that the job was “NOT a professional restoration.” The identity of the rogue “restorer” is unknown at this time.

For more information about the prior problematic restorations in Spain, please find a blog post from August 2020.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 31, 2020 |

Stories of ghosts, demons, and other horrors are common to all cultures, and most cultures around the world have art portraying the supernatural. Since ancient times, Japan’s religion and culture has been deeply bound with ghosts, called yūrei. Both feared and revered, yūrei are part of the deep magic; a foundational belief that humans have a god inside of them.

Stories of ghosts, demons, and other horrors are common to all cultures, and most cultures around the world have art portraying the supernatural. Since ancient times, Japan’s religion and culture has been deeply bound with ghosts, called yūrei. Both feared and revered, yūrei are part of the deep magic; a foundational belief that humans have a god inside of them.

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, born in 1839 in Japan, is known as one of the last great masters of the Japanese woodblock print. One of his masterpieces a series of works, 100 Ghost Stories from China and Japan. The series, created in 1865, includes images of skeletons, ghosts, and other supernatural creatures. One well-known print is Japanese samurai warrior, Oya Taro Mitsukuni watching a battle scene between armies of skeletons.

Leizhen (Raishin), MFA Boston

The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (MFA) owns Leizhen (Raishin), from the series. The work, signed by Ikkaisai Yoshitoshi ga, was purchased by William Sturgis Bigelow in 1911 and then gifted to the MFA. Bigelow was a prominent American collector of Japanese art. He lived in Japan for seven years. The Japanese government authorized him and two other Americans to explore parts of Japan that had been closed to outside viewers for centuries. During his time there, he acquired valuable art, including the mandala from the Hokke-do of Tōdai-ji, one of the oldest Japanese paintings to ever leave Japan. Bigelow donated approximately 75,000 objects of Japanese art to Boston MFA. Due to the huge donation, the still has the largest collection of Japanese art anywhere outside Japan.

Perhaps even more haunting is a series of fourteen works, the Pinturas Negras (Black Paintings), created between 1819 and 1823 by Spanish painter Francisco Goya. The works depict dark themes that reflected Goya’s own fears and his bleak view of humanity, in part due to the fact that the Spanish master was going deaf. At the age of 72, Goya moved into a home outside of Madrid known as La Quinta del Sordo (the Deaf Man’s Villa). The previous owner was deaf, and Goya was nearly deaf by the time he moved into the home. During this despairing time, Goya painted a series of unsettling works, such as murals on the walls of his house. They were eventually transferred to canvas.

Witches’ Sabbath, El Prado

One of the most macabre is the work now known (Goya did not title the murals) as the Witches’ Sabbath (El Aquelarre) or The Great He-Goat (El Gran Cabrón). Like most of the other works in the series, it was painted with dark and earth-toned colors. The painting depicts a witches Sabbath attended by the Devil in the form of a goat. The He-Goat appears as a silhouette painted entirely in black, except for one eye. Facing the demonic creature is a coven of witches and warlocks, portrayed with hideous features. The series of works was acquired by the Baron Emile d’Erlanger when he purchased the “Quinta” in 1873. He had the murals transferred to canvas, but they suffered great damage. The Baron ultimately donated the works to the government of Spain, which in turn moved them to the Prado, a national museum located in Madrid, to be publicly viewed.

The portrayal of devils and demons in works of art dates back millennia. Featured in The Exorcist, Pazuzu is the main antagonist who is exorcized from its victim. But the demon was not just the creation of the author of the The Exorcist, William Peter Blatty. The demon derives from Assyrian and Babylonian mythology, where it was considered the king of the demons of the wind, and the son of the god Hanbi.

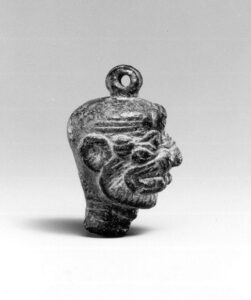

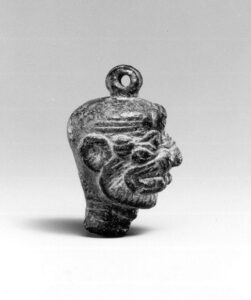

Pendant of Pazuzu, Metropolitan Museum of Art

On display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (the Met) is a small pendant of the demon, dating from the 8th to 7th century BC. The pendant has bulging eyes, bulbous forehead protrusions, and short beard that rings the snarling open mouth, atop an incongruously thin neck. These are his unmistakable features.

According to the Met, Pazuzu appears on many plaques and amulets, sometimes as a figure with wings and a scorpion tail. The earliest image of Pazuzu dates to the late 8th century B.C., relatively late in the history of demonic imagery in Mesopotamia. The museum states that this was a period when the Assyrian royal administration was intensely focused on collecting magical knowledge and studying the supernatural world, and priests and exorcists were actively engaged in codifying these systems of knowledge. As a result, a rich variety of magical images and texts from Assyria in this period have survived. The pendant was sold at Hôtel Drouot, Paris, on May 19-20, 1987, and eventually it was acquired by the museum in 1993, purchased at Sotheby’s New York, on June 12, 1993.

In addition to the demonic pendant, the Met owns other spooky art, including this photograph of a ghostly apparition.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 29, 2020 |

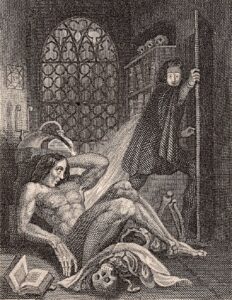

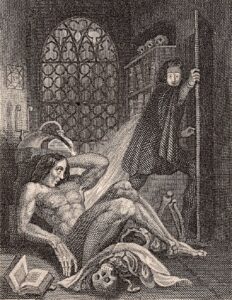

Illustration from the frontispiece of the revised edition of Frankenstein, published by Colburn and Bentley, London 1831.

Some of Hollywood’s most famous “monsters,” jumped off the pages of Gothic novels to the excitement and fear of spellbound readers. One of the most famous is the monster from Frankenstein. At the young age of just 18, Mary Shelley created a tale that would fill readers with dread, as well as empathy. Frankenstein, the Modern Prometheus, was a being imbued with humanity seeking love and acceptance. The teenage Mary Shelley created her tale during a ghost-story competition one stormy evening in the summer of 1816 while on holiday in Switzerland with Percy Shelley, Lord Byron, Claire Clairmont and John Polidori. During the course of her edits, the “monster” evolved from a “being” to a more human creature, and the book was first published in 1818.

As Mary Shelley’s horror story shaped Gothic literature, her copious notes and edits have been studied by historians, academics, and fans of the novel. The pages are now available online to viewers around the world on the Shelley–Godwin Archive. The original transcript is currently in the Bodleian Libraries at Oxford as part of the Abinger Collection. The collection was given to the university, in batches between 1974 and 1993, by James Scarlett, 8th Lord Abinger.

The Abinger papers are the residue of the collection of the Shelley family’s papers from Boscombe Manor (near Bournemouth, Dorset), the home of Sir Percy Florence Shelley, 3rd Baronet of Castle Goring (1819-1889), and his wife Jane, Lady Shelley (1820-1899). Sir Percy had inherited the family archive from his mother, Mary Shelley. She maintained papers from her parents, her husband, and from her own writing.

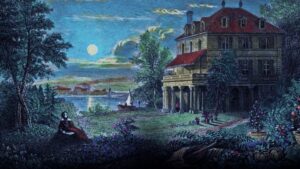

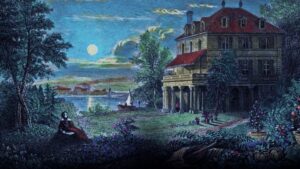

Villa Diodati, near Geneva, where literary character Frankenstein was created in 1816. (Credit: DeAgostini/Getty Images)

Since Mary Shelley had a close relationship with her daughter-in-law, it was Lady Shelley (Jane Shalley) who cared for and acquired additional items for the family archive. After her husband’s death, Lady Shelley endowed the Shelley Memorial at University College (1893) and she gave selected notebooks, letters and relics to the Bodleian Library (1893 and 1894). She bequeathed most of Mary Shelley’s other notebooks, relics, and papers to her husband’s cousin and the heir to his baronetcy, John Courtown Edward Shelley, later known Sir John Shelley-Rolls (1871-1951). Sir John gave the notebooks to the Bodleian Library in 1946.

Jane Shelley bequeathed her houses with their residual contents to her two eldest grandsons, Shelley and Robert Scarlett. Eventually, Shelley and Robert became respectively the 5th and 6th Barons Abinger, both childless. The majority of the papers were passed to their brother Hugh, the 7th Baron Abinger. When Hugh’s son James became the 8th Baron Abinger in 1943, he took a serious interest in the family papers. In the early 1970s, Lord Abinger gave permission for the Shelleys’ joint journal to be prepared for publication by Oxford University Press, and deposited the original journals at the Bodleian for the editors’ use. This led to Lord Abinger’s decision to provide the entire collection on long-term loan at the Bodleian in nine batches between 1974-1993.

Lord Abinger’s son James succeeded him in 2002. He put the papers on the market, but gave the right of first refusal to the Bodleian Library. The library launched a campaign to raise the funds. This mission was accomplished in 2004, when the Abinger collection was bought outright by the Bodleian Library with donations from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the Carl and Lily Pforzheimer Foundation, and many other institutional and individual donors. Cataloguing of the papers was completed in 2010 with the aid of a grant from the John R. Murray Charitable Trust.

The information presented in this post can be found HERE.

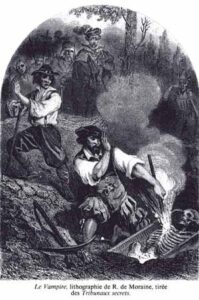

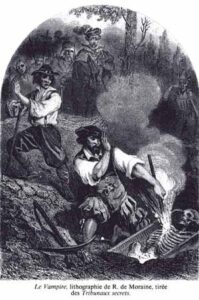

Vlad Tepes dining while surrounded by the impaled bodies of his enemies; hence, the name “Vlad the Impaler.”

Another horror novel that has haunted generations of readers is Dracula. Inspired by tales of ruthless acts of violence and revenge exacted upon the Ottoman enemies of Vlad III (Vlad the Impaler, Vlad Tepes, or Vlad Dracula), Bram Stoker portrayed the Romanian ruler as a vampire and incorporated Romanian folklore about vampires in his novel. Written between 1890 and 1897, it is Stoker’s best known work. Count Dracula is one of the most filmed characters, and the tale has inspired countless other works, films, theatrical productions, and cultural references.

Nevertheless, the original manuscript had disappeared for decades. In a story worthy of the famous Gothic novel, the manuscript was lost and eventually found. In the 1980s, the heirs of Thomas Corwin Donaldson (a friend of both Bram Stoker and Walt Whitman) unearthed the manuscript of Dracula in a barn in Pennsylvania. Donaldson’s heirs sold the papers and manuscript through Peter Howard of Serendipity Books in Berkeley, California. Howard offered it to another book dealer and collector, John McLaughlin (owner of The Book Sail in Orange County, California). McLaughlin’s 1984 catalog lists the manuscript. Due to financial concerns, in 2002, McLaughlin consigned the manuscript to auction at Christie’s in New York.

The manuscript is complete with Stoker’s original handwritten title, The Un-Dead (Stoker changed the title only days before the publication in 1897). The manuscript failed to sell went it went to auction in 2002 at Christie’s in NY. It is signed or initialled by Stoker in many places and contains a different ending to the final one published in 1897, and it was expected to fetch £1m. Since it failed to reach its undisclosed reserve price, it did not sell at auction. However, the novel was later sold privately through Christie’s to Paul G. Allen, co-founder of Microsoft. Allen passed away in 2018, and the manuscript presumably remains in his estate.

The manuscript is complete with Stoker’s original handwritten title, The Un-Dead (Stoker changed the title only days before the publication in 1897). The manuscript failed to sell went it went to auction in 2002 at Christie’s in NY. It is signed or initialled by Stoker in many places and contains a different ending to the final one published in 1897, and it was expected to fetch £1m. Since it failed to reach its undisclosed reserve price, it did not sell at auction. However, the novel was later sold privately through Christie’s to Paul G. Allen, co-founder of Microsoft. Allen passed away in 2018, and the manuscript presumably remains in his estate.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 11, 2020 |

Leila A. Amineddoleh will be presenting at New York County Lawyers’ Associations’ 12th Annual Art Litigation/Dispute Resolution Institute on Friday, October 16. Leila will be presenting on the topic of title and ownership disputes. The conference is a highlight for NYC’s art law community. Now that it is being held virtually, the event is more easily accessible to practitioners in other jurisdictions. For more information about the conference, visit https://www.nycla.org/NYCLA/Events/Event_Display.aspx?EventKey=CLE101620

Stories of ghosts, demons, and other horrors are common to all cultures, and most cultures around the world have art portraying the supernatural. Since ancient times, Japan’s religion and culture has been deeply bound with ghosts, called yūrei. Both feared and revered, yūrei are part of the deep magic; a foundational belief that humans have a god inside of them.

Stories of ghosts, demons, and other horrors are common to all cultures, and most cultures around the world have art portraying the supernatural. Since ancient times, Japan’s religion and culture has been deeply bound with ghosts, called yūrei. Both feared and revered, yūrei are part of the deep magic; a foundational belief that humans have a god inside of them.

The manuscript is complete with Stoker’s original handwritten title, The Un-Dead (Stoker changed the title only days before the publication in 1897). The manuscript failed to sell went it went to auction in 2002 at Christie’s in NY. It is signed or initialled by Stoker in many places and contains a different ending to the final one published in 1897, and it was expected to fetch £1m. Since it failed to reach its undisclosed reserve price, it did not sell at auction. However, the novel was later sold privately through Christie’s to Paul G. Allen, co-founder of Microsoft. Allen passed away in 2018, and the manuscript presumably remains in his estate.

The manuscript is complete with Stoker’s original handwritten title, The Un-Dead (Stoker changed the title only days before the publication in 1897). The manuscript failed to sell went it went to auction in 2002 at Christie’s in NY. It is signed or initialled by Stoker in many places and contains a different ending to the final one published in 1897, and it was expected to fetch £1m. Since it failed to reach its undisclosed reserve price, it did not sell at auction. However, the novel was later sold privately through Christie’s to Paul G. Allen, co-founder of Microsoft. Allen passed away in 2018, and the manuscript presumably remains in his estate.