by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Dec 1, 2020 |

The Chess Game, Sofonisba Anguissola (1555 – National Museum Poznań)

The Queen’s Gambit on Netflix has recently been credited with helping to fuel a chess renaissance. The series about an orphan with a preternatural mastery of chess features a beautiful wardrobe for its main protagonist, 1960s music, and high-stakes international tournaments. With the onset of winter and a second round of lockdown looming over many countries, people are turning to games – such as chess – for a respite. Sales of chess sets and accessories have skyrocketed as much as 215%, with interest mainly in wooden and vintage sets. Millions are subscribing to and playing matches on websites, breaking existing records.

However, chess’ popularity predates the current craze. For centuries, military strategists, royalty, children and others have enjoyed this board game, which is one of the oldest in the world. Chess is believed to have originated in northwest India before spreading along the Silk Road, eventually reaching Western Europe via Persia and Islamic Iberia. The oldest archaeological chess artifacts, made of ivory, were excavated in Uzbekistan and date to approximately 760 A.D. Chess has been depicted in numerous artworks, literature, and films, including a memorable match in the Harry Potter franchise and a painting by Sofonisba Anguissola (pictured above).

Lewis Chessman (Photo: British Museum)

Antique chess pieces are not only historically important, but also offer a fascinating glimpse into artistic, commercial, and cultural trends. The Lewis Chessmen, discovered in 1831, are possibly the finest known example of medieval European ivory chess pieces. They are believed to be the first chess pieces to depict bishops and they possess distinctly human forms. The set was discovered on the island of Lewis in Scotland, as part of a hoard containing 93 artifacts in total. The pieces date back to the 12th or 13th century, with 82 pieces forming part of the British Museum’s collection and 11 pieces held by National Museums Scotland. The chess pieces were likely made in Trondheim, Norway from walrus ivory and teeth. They exhibit many interesting details, such as bulging eyes and a rook (depicted as a standing soldier or “warder”) biting its shield like a Viking berserker. The pieces reflect the ties between Scandinavia and Scotland at the time the carvings were made. Interestingly, the Lewis Chessmen were among the first medieval antiquities acquired by the British Museum, and they have also been featured as #61 in the 2010 BBC Radio series A History of the World in 100 Objects.

As with all artwork and artifacts, provenance is extremely important. In fact, if may even be more important for chess pieces, which are portable in nature and thus prone to separation and forgery. It is rare for entire sets to survive intact; some pieces in circulation are even high-profile copies of masterpieces, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s reproductions. The Met’s collection even includes copies of certain Lewis Chessmen. The Lewis pieces’ provenance prior to its discovery in 1831 is unknown, although they may have been the property of a merchant or a local leader, buried for safeguarding or for future trade with Iceland. In fact, there are conflicting accounts of their discovery. Supposedly, Malcolm MacLeod discovered the trove in a dune, exhibited the chess set for a brief period, and then sold the pieces to Captain Roderick Ryrie. Ryrie then exhibited the pieces at a meeting of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in April 1831, and the set was split up shortly after. Ultimately, the British Museum purchased the majority of the pieces for £84 on the recommendation of chess enthusiast Sir Frederic Madden. This proved to be a solid investment, as one of the chess set’s related pieces (a previously unrecognized warder) was sold in July 2019 at Sotheby’s for £735,000. It had been bought by an antiques dealer in Edinburgh for £5 fifty-five years before, and the dealer’s family had no idea of the object’s importance until the family submitted it for appraisal. The warder was described as “characterful” and as having “real presence” by Sotheby’s expert Alexander Kader.

Man Ray Chess Set

While the Lewis Chessmen are exceptional, they are not the only chess sets to have achieved fame. The Charlemagne Chess Set, currently held by the National Library of France in Paris, was made in Salerno, Italy in the late 11th century. It formed part of the treasury of the Basilica of Saint Denis and has unusual dimensions. The set is seen as symbolic, depicting the various roles of individuals in medieval society. Yet despite its name, it never belonged to Charlemagne. And unfortunately, only 16 pieces are left from the 30 inventoried in the 16th century. The Àger chess pieces are another unique example of the game, as they were crafted from rock crystal. Believed to have been made in Egypt, Iraq or eastern Iraq during the 9th century, they were deposited in the Àger monastery in present-day Catalonia, Spain during the 11th century. As the chess set has an Islamic origin, the pieces are not humans but rather present an abstract style with arabesque decorations. Finally, Surrealist artist Man Ray produced a modern design for a chess set inspired by everyday objects. These were then reduced to simple, semi-abstract forms: the knight was represented by a violin scroll, the bishop by a flask, and the king by an Egyptian pyramid. Reproductions of Man Ray’s are available to players at all price points.

We hope you have enjoyed this journey through the fascinating world of chess. Amineddoleh & Associates is proud to represent collectors in pursuing their creative passions, whether that is through the sale of artwork or by acquiring antique board games that display craftsmanship and historical value. Collectors should always remember to perform due diligence and consult experienced legal professionals when considering art and cultural property-related transactions.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Nov 30, 2020 |

Our founder appeared on an episode of the Wedding Industry Law Podcast to discuss intellectual property rights. The link is available here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QFxUq4aOgqw

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Nov 25, 2020 |

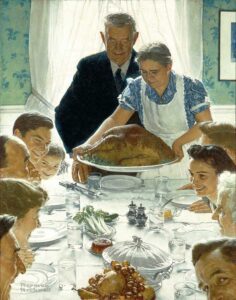

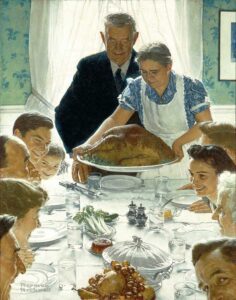

Freedom from Want, 1943. Norman Rockwell Museum Collections. ©SEPS: Curtis Licensing, Indianapolis, IN.

For many, Thanksgiving is the quintessential American holiday. It represents a sense of warmth, home, family, and tradition. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Norman Rockwell’s emblematic artwork. Rockwell was a 20th century author, painter, and illustrator whose cover illustrations graced the Saturday Evening Post magazine for nearly fifty years. Rockwell created several Thanksgiving paintings and illustrations, ranging from the heartwarming to the humorous. The most well-known of these is likely Freedom From Want (also known as The Thanksgiving Picture or I’ll Be Home for Christmas), which depicts a grandmother serving her family with a delicious turkey. The painting was inspired by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1941 State of the Union Address and features the artist’s friends and family. An earlier illustration from 1917 titled Cousin Reginald Catches the Thanksgiving Turkey demonstrates Rockwell’s fanciful side, as it shows a turkey chasing a young boy – the hunter becoming the hunted.

Courtesy: FBI

Rockwell’s paintings have stood the test of time. Although in the 1950s there was little demand for these items, their current market value ranges into the millions. The current auction record for a Norman Rockwell is over $46 million; in the past decade alone, four works have fetched more than $10 million each at auction. It should come as no surprise that a recently recovered painting of a slumbering child has a current fair market value of approximately $1 million. The painting – known variously as Taking a Break, Lazybones, and Boy Asleep with Hoe – was stolen in 1976 from the private residence of the Grant family, where it had hung for nearly 20 years. In 2016, the FBI Art Crime Team issued a news release marking the 40th anniversary of the theft in an effort to generate interest and potential leads. The gamble worked; an antiques dealer recognized the painting and handed it over to the FBI. Interestingly, Chubb Insurance had paid $15,000 for the painting when the Grants made a claim after the theft occurred in 1976, making it the owner of the work. The Grants opted to return that amount to the insurance provider in exchange for ownership rights over the work, and Chubb donated the funds to the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. All’s well that ends well, although John Grant did mention that he wasn’t going to tempt fate by keeping the painting in his house. The painting was subsequently offered at auction in Dallas and sold for $912,500.

Amineddoleh & Associates wishes you a safe, happy and prosperous Thanksgiving!

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Nov 20, 2020 |

Golden Coffin of Nedjemankh– looted from Egypt and sold with false provenance

The Victoria & Albert Museum in London is currently closed, but it continues to create and distribute valuable content examining issues related to art and heritage looting. Through Culture in Crisis, a program bringing together individuals and organizations with a shared interest in protecting cultural heritage, the museum is actively engaging with heritage professionals to provide insights into the dangers facing our shared history. One tool for raising awareness of these issues is the Culture in Crisis Podcast.

Season Two, Fighting the Illicit Trade, is comprised of interviews with international experts working to prevent the illegal trade of cultural heritage– each person fighting a battle to rescue cultural heritage at a different stage of its underground journey. The series examines the actions taken at the object’s source, through transit, and upon arrival at its destination. As stated by Culture in Crisis, “The theft and sale of cultural property robs communities of their past, present and future. It lines the pockets of international criminal networks and has been shown to directly finance terrorism. Through this series we hope to highlight valuable initiatives working to prevent the illicit trade and gather recommendations on how to build on these efforts in the future.”

Our founder, Leila A. Amineddoleh, is interviewed in Episode 7, “You’ve Gotta Have (Good) Faith.” She offers a legal perspective about heritage looting, discussing legal cases, provenance (including false provenances), good faith purchases, and the due diligence involved in purchasing antiquities. Read more about the series and listen to the informative interviews here.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Nov 13, 2020 |

ALERT: Art market participants should be aware that OFAC has issued an advisory concerning high-value artwork, defined as that which has an estimated market value of more than $100,000. Violating OFAC regulations constitutes a strict liability offense, meaning that the accused party need not have knowledge that a person or intermediary has been blocked or sanctioned to be found liable. When engaging in a transaction involving high-value artwork, art market participants should consult OFAC’s List of Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (SDN List) and potentially request a license from OFAC. They should also implement compliance programs to help minimize risk across the board and consult with legal counsel regarding specific vulnerabilities.

On October 30, 2020, the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) within the U.S. Department of the Treasury issued an advisory to art market participants, concerning dealings in high-value artwork. OFAC considers “high-value artwork” as that which has an estimated market value of more than $100,000. The advisory follows the release of an extensive Senate report in July 2020, whose findings revealed how two Russian oligarchs used the U.S. art market to evade sanctions for years. Notably, the bipartisan report detailed how a relatively lax regulatory approach to the art market in the US has created “an environment ripe for laundering money and evading sanctions.” The report recommends amending the Bank Secrecy Act, adding high-value art to the list of regulated transactions that require background checks and identity verification. Unlike the EU and UK, the US does not have anti-money laundering regulations for art market participants in place.

OFAC is now putting art market participants on notice that they may be at risk of sanctions when dealing in high-value artwork, if transactions ultimately involve blocked persons (particularly those on OFAC’s List of Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons, or SDN List). OFAC’s advisory and guidance urges art market participants – including art galleries, museums, private art collectors, auction houses, agents, and brokers – to implement and maintain risk-based compliance programs as a mitigating measure. Since the art market operates with a lack of transparency and a high degree of anonymity, blocked persons can (and do) evade sanctions by using third parties and shell companies to complete transactions. These transactions are not automatically exempt from OFAC regulations, and may result in million-dollar fines.

It appears the trend towards art market regulation in the US will continue, particularly in light of COVID-19’s effects on online risks. OFAC’s advisory is likely a precursor to future legislative action, and art market participants should therefore be cautious when it comes to high-value artwork.