Leila A. Amineddoleh named as a leading female art lawyer

Art She Says names Leila A. Amineddoleh on its Power List of the Top Female Attorneys in the Art World. The article emphasizes her work in the realm of art authentication. Read more here.

Art She Says names Leila A. Amineddoleh on its Power List of the Top Female Attorneys in the Art World. The article emphasizes her work in the realm of art authentication. Read more here.

The new year is a time for both reflection and projection. It encourages us to contemplate the trials and triumphs of the year, but it also provides us with the opportunity to look forward to what lies ahead with hope. This year, in particular, people around the globe are eager to ring in a new year, with optimism for a return to a more normal world. As we all look to the future with anticipation, we give pause to examine one of humanity’s first new year celebrations- Akitu.

Sometimes called Akitum, Akitu was a twelve-day celebration originating in ancient Mesopotamian Babylon. Beginning at the start of the spring and coinciding with the first sowing of barley, the festival marked the start of the Babylonian calendar. Akitu was more than a simple agricultural festival, however, it was a vehicle for political and social change, and it became central to the Babylonian religion over time.

Rconstruction of the Ishtar Gate at the ruins of Babylon, in modern day Iraq © Jukka Palm/Dreamstime.com

Festivities and rites were mostly conducted in two locations, the Ésagila (temple of the supreme god Marduk) and the ‘house of the New Year.’ The priest of the Ésagila would begin the festival with a series of pleading prayers to Marduk, answered by other priests and citizens with additional calls for protection and forgiveness. This continued for three days, purportedly an expression of fear of the unknown and the chaotic forces of the ancient world. At the end of the fourth day, the priest would recount the earliest Babylonian myth of creation and the ascension of Marduk as the supreme deity over the primordial gods.

During this time, the King of Babylon was required to leave the city and relocate to a temple in the city Borsippa, 17 kilometers south of Babylon. The king would reenter Babylon on the fifth day of Akitu, and enter the Ésagila. There, the priest acting as Marduk would strip the king of all refinery: jewelry, weapons, and even his scepter and crown. The king pled with Marduk that he had ruled without sin, at which point the priest would forcefully slap the king across the face in the hopes of inducing tears. A tearful king served as a symbol of the king’s submission to a higher power. Once the requisite tears were shed, the king would be returned his regalia, imbued with the divine power to rule another year. The festival then continued with several days of reenacting battles between gods using statues and puppets.

The celebration ended with the presentment of the holy statues to the people of Babylon via a parade led by the king. Babylonian government officials would make speeches about the city’s policies for the incoming year. This policy was seemingly always one of blessing, fortune, and success. It was well received by the populace, who would reply with the joyous singing of various hymns.

Photo courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art

Remnants of the Babylonian new year celebration are in museums around the world, including a glazed brick panel at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (the “Met”). It depicts a striding lion, circa 604-562 B.C. The lion is one of many that decorated the Processional Way, leading from the inner city through the Ishtar Gate to the house of the New Year. It would have presided over the parades of deities during Akitu. Lions are a symbol of the goddess Ishtar, wife to Marduk, and whose image was evoked to protect this most important street in Babylon. The Ishtar Gate was built by Nebuchadnezzar II, who brought the Babylonian empire to new heights through his mastery of diplomacy and warfare, as described by Herodotus and the Old Testament.

The piece owned by the Met was excavated in 1902 by German archeologist, Robert Koldewey, on behalf of the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft (German Oriental Society). Koldewey is highly regarded for directing the first prominent excavation of Babylon, which employed more than 200 people daily, year-round, from 1899 to 1914. He is credited with the discovery of the Ishtar Gate and the Processional street, where this piece was likely found. He also pioneered advanced methods of identifying and excavating mud brick architecture. In addition, he claimed to have discovered the famed Hanging Gardens of Babylon built by King Nebuchadnezzar. However, subsequent findings and analysis shed some doubt on this conclusion.

The excavation of Babylon generated considerable excitement in Germany, and thus Koldewey’s excavation was accordingly well funded during its fifteen years. The glazed piece was ceded to one of Germany’s national museums, the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin. The institution boasts one of the world’s largest collections of ancient Middle Eastern and Southwest Asian art, including artifacts from historically important cities such as Uruk, Shuruppak, Assur, Hattusha, Tell el Amarna, Tell Halaf (Guzana), Sam’al, and Toprakkale. The Ishtar Gate itself resides within the Berlin museum, reconstructed after its excavation in Babylon. The glazed brick panel was acquired by the Met in 1931.

The god Janus, Roman coin; in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris

Larousse

The celebration of Akitu includes timeless aspects of new year celebrations. Dating back to the first civilizations, humans have taken stock at the end of the year and set goals for what to achieve in the twelve months to come. The practice of Akitu, which became popular throughout Mesopotamia, did not end with the fall of Babylon. By the third century A.D., Akitu was celebrated in Syria to honor of the sun god Elagabal. The holiday even made its way to Italy for a time via the Roman emperor Elagabalus, a Syrian native, who adopted the holiday during his short reign from 218 to 222. But the festival was not adapted as a celebration of the new year. The Romans continued to celebrate the occasion at the start of month of Janus, eventually becoming the new year we celebrate today.

Happy New Year from all of us at Amineddoleh & Associates!

Nativity scenes – or depictions of the Holy Family, angels and shepherds adoring the newborn Jesus – are common in Christian iconography, particularly during the Christmas season. Italian churches often commemorate the holiday with elaborate nativity scenes, or presepe, populated with dozens of figures from everyday life. In Naples, the tradition has extended to include celebrities and world leaders in addition to villagers and shopkeepers. One local craftsman even makes his presepe out of pizza dough. The world’s first nativity scene is attributed to Saint Francis of Assisi. He staged his production, in 1223, in a cave near Greccio, Italy. Saint Francis is said to have been inspired during a pilgrimage to the Holy Land where he visited Jesus’s traditional birthplace. Once back in Italy, he sought to direct the celebration of Christmas away from gift giving back to the worship of Christ. His presepe used live actors and farm animals to recreate the now famous biblical scene. The world’s first live nativity scene was an instant success, receiving the blessing of Pope Honorius III.

Elaborate Presepe, courtesy of Evelyn Dungca

Thereafter, nativity scenes became widely popular, becoming a staple in every Italian church within a hundred years. As statues began to replace live actors, nativity scenes attracted notable collectors such as Charles III, King of the Two Sicilies, who helped spread their popularity internationally. Many nations have since adopted their own unique style of nativity, including hand-painted santons in Provence, France; hand-cut wooden figures in Austria and Germany; intricate szopka in Poland; and inclusion of a Caganer (a defecating figure) in nativity scenes in Catalonia, Spain. A tradition emerged in England to eat a mince pie in the shape of a manger during Christmas dinner, a practice which was eventually outlawed by Puritans in the 17th century, calling them “Idolaterie in crust.” Despite this temporary prohibition, nativities are now found throughout the world, in locations ranging from religious institutions to shopping malls, and whose inclusion on public land has even sparked legal controversy in the U.S. Some reoccurring nativity scenes, such as the Vatican’s annual production in St. Peter’s Square and the Metropolitan’s baroque nativity scene in its Medieval Art section, have become famous in their own right. In contrast to these large-scale pieces of pageantry, painted depictions of the nativity are usually placed in an intimate setting and invite the viewer to engage in contemplation.

In honor of the Christmas holiday, we also examine the magnificent painting Nativity with Saints Lawrence and Francis by Italian Baroque artist Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. The work was painted in 1609 in Palermo, Sicily, where Caravaggio relocated after fleeing from Rome after murdering a man, committed after a fight over a tennis match. Caravaggio was recognized for his volatile personality and his dramatic paintings in the chiaroscuro style. His life has been described as “a negroni cocktail of high art and street crime.” Despite his moral failings, Caravaggio’s stunning Nativity held pride of place over the altar in Palermo’s Oratory of San Lorenzo for 360 years, until unidentified criminals stole the painting in 1969. During an autumn storm, thieves carefully removed the painting by cutting the canvas from the wall. They fled and escaped with their prize rolled up in a carpet. Given that the painting measures three by two meters, and the skillful nature of its removal, many experts believe the most likely culprits are members of the organized crime group Cosa Nostra, also known as the Sicilian mafia. There is tragic symmetry that a work first conceived following a terrible crime has since been lost to the criminal underworld.

Caravaggio, Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence

Cosa Nostra is no stranger to the world of art crime. In 2016, two stolen Van Gogh paintings were recovered at the Italian home of a drug smuggler with ties to the mafia. The paintings are worth an estimated $56 million (50 million euro) each and had been missing for 14 years, since their theft from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. This precedent, along with testimony from witnesses inside the criminal organization, has led Italian law enforcement to believe that Caravaggio’s missing Nativity is potentially in Cosa Nostra’s hands. However, the self-serving nature of testimony from witnesses who wish to escape criminal charges is not always reliable. Furthermore, there have been conflicting accounts of the Nativity’s fate. Some have said that the work is still whole; others, that it was cut into pieces to facilitate its sale; and finally, that the painting had been stashed in a barn where it was consumed by rats and hogs, and ultimately burned.

Currently, it is impossible to say where the Nativity is, or in what state of disrepair. The theft is considered one of the most significant art crimes in history, and the Carabinieri, Interpol, and the FBI have all collaborated in the investigation. New information has come to light within the past two years indicating that the painting may be “still alive” and in circulation in Europe. The painting could be in criminal hands, serving as collateral for drug deals and kept as a bargaining chip for future negotiations with law enforcement. Prosecutors continue to follow the trail of breadcrumbs and hope that they will meet with success. Importantly, although the Nativity’s value has been estimated at $20 million, its black market resale price would be much less – possibly a tenth of the total value.

There is a bittersweet coda to this saga, as a life-size reproduction of the Nativity was commissioned in 2015. The replica, created by Factum Arte, is the result of painstaking research melded with technology. The company used a slide of the painting and black-and-white photographs to study the composition and surface of the work, including brush marks. To recreate the colors used by Caravaggio, technicians based their reproduction on the artist’s paintings in the Church of San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome, which date from approximately the same period. While a facsimile is no substitute for the real thing, it gives viewers a chance to appreciate the Nativity’s “lost beauty” and learn about how technology can be used to create detailed reproductions of works that have been lost or damaged. The replica currently occupies the Nativity’s original location as a placeholder until the painting can be found. Hopefully, authorities will be able to recover this masterpiece and return it to its rightful place.

Amineddoleh & Associates wishes you all a safe and joyful holiday season.

Season’s greetings from all of us at Amineddoleh & Associates!

Like so many of you, all of us at Amineddoleh & Associates missed meeting with our friends and colleagues this year, but we send you warm wishes for a happy and healthy holiday season and a prosperous 2021. Although 2020 was a challenging year, it was also a banner year for the firm. In addition to securing a win for the Greek government in a landmark litigation against Sotheby’s auction house and its consignors in Barnet et. al v. Ministry of Culture and Sports of Hellenic Republic, we were also retained by the Republic of Italy in another cultural heritage dispute, Safani v. Republic of Italy. In this case, we are representing Italy in a lawsuit involving an antiquity excavated from the Roman Forum and potentially stolen from a national museum.

In addition to these high-profile representations, we continue to work with clients on a variety of intellectual property, art and cultural heritage, and estate matters. Below are some of the highlights of this year:

2020 was also an exciting year for our team in terms of professional achievements and accolades. Leila was honored to speak at the Frick Collection on the importance of provenance. During the lockdown, she participated in a podcast series for the Victoria & Albert Museum, and she also discussed art and heritage issues for various educational institutions, including the American Bar Association, American University, Wake Forest University School of Law, and Christie’s Education. In addition, she served as a cultural heritage law expert on Turkish television channel TRT World, published a law review article about the political dimensions of cultural heritage, and appeared in a number of news sources, including the LA Times, ABC News, Artnet, and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. Leila also contributed a chapter, addressing the legal implications of art and antiquities’ provenance, to the recently-published volume Provenance Research Today: Principles, Practice, Problems.

Claudia completed a year-long legal internship at Constantine Cannon in London, where she worked on a cultural heritage legislative drafting project and developed multiple proposals for the Global Legal Hackathon with teams from the UK, Italy, US, and South Africa. She has multiple journal articles scheduled for publication in 2021, and she will serve as a panelist at the TIAMSA Conference in July 2021, discussing the role of deaccession in museum practice and its overlap with diversity initiatives.

We look forward to a productive year ahead and what are sure to be interesting developments in the field of intellectual property and art and cultural heritage law.

HAPPY HOLIDAYS!

Today, December 21, marks the Winter Solstice, the first day of winter. To celebrate, we are examining how the season was depicted in landscape paintings during the 16th Century.

Hunters in the Snow

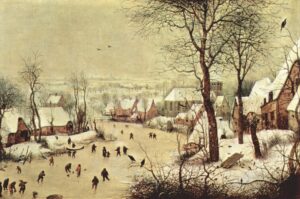

Winter was a frequent subject for Flemish painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder. His extraordinarily detailed paintings use winter as a symbol for the passage of time. For instance, Hunters in the Snow (1565) perfectly depicts a wintertime village, complete with ice skaters in the distance, swooping birds, and minutely rendered bare tree branches. Winter Landscape with Skaters and Bird Trap, painted during the same year, is unique for its rendering of winter light in gradations of white, ivory, and yellow. Bruegel’s work is notable for its realism at a time when many artists preferred to depict idealized versions of nature. However, Hunters in the Snow is not entirely accurate; Bruegel transposed elements from his travels to Italy (specifically the Alps) into the flat Dutch landscape.

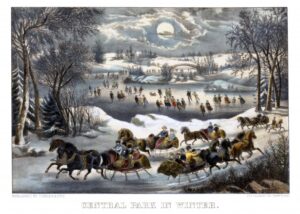

Winter Landscape with Skaters and Bird Trap

Bruegel’s son, Pieter Bruegel the Younger, continued this tradition with Adoration of the Magi in the Snow. As is common with Flemish painting from this period, the main figures are located to the side and surrounded by a crowd, allowing the artist to create an expansive scene and set the narrative in a wider context. In the Adoration, donkeys laden with exotic gifts for the Christ child are led through a throng of villagers as snow falls. Bruegel the Elder had previously tackled the same subject in 1563, although the figures of the Holy Family in his version are indistinct when seen from a distance, obscured by a blizzard. The snow renders the villagers’ everyday tasks – chopping wood, carrying water, setting out to hunt – almost magical.

Bruegel the Younger, Adoration of the Magi in the Snow

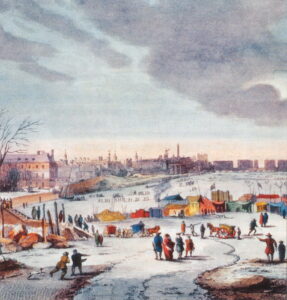

These paintings are not only beautiful, but they also offer a glimpse into the daily life of people five centuries ago. During the period when the Bruegels were active, Europe was in the grip of what is known as the “Little Ice Age,” which caused particularly cold and harsh winters. Rivers froze solid enough to allow merchants to set up shop on the water semi-permanently. The Thames Frost Fairs in London are a notable example. The most famous frost fair, called The Blanket Fair, was held during the Great Winter of 1683-84. It included many activities for attendees of all ages, such as ice skating, horse and coach races, and puppet plays. King Charles II is said to have attended the fair and enjoyed a bite of spit-roasted ox.

However, the extreme temperatures also led to food shortages, flooding, and may even have spurred the witch hunts. Ultimately, thousands of people died from illness and frostbite.

Although these paintings depict nature at its harshest, they can be uplifting as well. The winter landscapes allowed the Bruegels to experiment with composition and color, while breathing new life into the subject. Their virtuosity led to winter landscapes becoming embraced as a new and popular genre for patrons and artists while creating works that thousands of art lovers enjoy to this day.

Thomas Wyke, Thames Frost Fair

We hope you have enjoyed this tour through winters past. As the new year approaches, Amineddoleh & Associates wishes you all a prosperous 2021 and best wishes for this winter.