by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Feb 28, 2021 |

It is a bitter truth that women, who are so often depicted, admired and romanticized through art, have had to overcome herculean obstacles to participate in its creation. In honor of Women’s History Month, this entry in our Provenance Series examines the work of the Old Masters’ female counterparts – the Old Mistresses – and their contemporary successors.

Rediscovery of Female Artists

Plautilla Nelli’s Last Supper (prior to restoration)

Renaissance and Baroque works by women have deservedly entered the public consciousness in recent years. In 2019, a depiction of the Last Supper by nun Plautilla Nelli was installed in the Santa Maria Novella Museum in Florence, after a painstaking 4-year restoration by the Advancing Women Artists Foundation (AWA). The project was made possible through the AWA’s “adopt an apostle” crowdsourcing program: private financiers were allowed to “adopt” one of the life-sized disciples at $10,000 each (ever-unpopular Judas was instead funded by 10 backers at only $1,000 each). The oil painting, measuring 21 feet across, is one of the largest Renaissance works by a female artist still in existence. It is also the only work created by a woman during the Renaissance depicting the Last Supper.

The Provenance and Restoration of Plautilla Nelli’s The Last Supper

Santa Maria Novella in Florence, Italy (Courtesy of CAHKT/iStock.com)

The Last Supper was likely created for the benefit of Plautilla’s own convent, the convent of Santa Caterina di Cafaggio in Florence, where it hung in the refectory (dining hall) until the Napoleonic suppression in the 19th century, when the convent was dissolved. It was thereafter acquired by the Florentine Monastery of Santa Maria Novella in 1817. Again, it was housed in the refectory until being moved to a new location in 1865. Scholar Giovanna Pierattini reports it was moved to storage in 1911, where it remained until 1939. It then underwent significant restoration, and returned to the refectory. It would remain on display there for almost forty years, surviving the historic flood of the Arno in 1966 with little damage. The work was next taken down in 1982, when the refectory was reclassified as the Santa Maria Novella Museum, and transferred to the friars’ private rooms. This is how the monumental work, which remained out of the public eye for centuries, is now visible to the public for the first time in 450 years.

Rossella Lari, the restoration’s head conservator remarks, “We restored the canvas and, while doing so, rediscovered Nelli’s story and her personality. She had powerful brushstrokes and loaded her brushes with paint.” The painting features emotionally charged expressions, emphatic body language, and exquisite details, such as the inclusion of customary Tuscan cuisine (roasted lamb and fava beans).

Plautilla’s use of color and composition is even more impressive when one considers that women were barred from attending art schools and studying the male nude; instead, they were forced to rely on printed manuals and the works of other artists. Plautilla was not only a self-taught artist, but she also ran an all-woman workshop in her convent and received the ultimate praise for an Italian Renaissance painter: inclusion in Giorgio Vasari’s seminal book Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects. Notably, in Plautilla’s time the convent was managed by Dominican friars previously under the leadership of fire-and-brimstone preacher Girolamo Savonarola. The nuns were encouraged to paint devotional pictures in order to ward off sloth. Undeterred, “Plautilla knew what she wanted and had control enough of her craft to achieve it,” says Lari. The Last Supper is signed “Sister Plautilla – Orate pro pictora” (“pray for the paintress”). Plautilla thus confirmed her role as an artist while acknowledging her gender, understanding that the two were not mutually exclusive. Although only a handful of the works survive today, Plautilla and her disciples created dozens of large-scale paintings, wood lunettes, book illustrations, and drawings with great focus, determination, and discipline. She is considered the first true woman artist in Florence and in her heyday, “There were so many of her paintings in the houses of gentlemen in Florence, it would be tedious to mention them all.” Since AWA’s conservation work was initiated, the number of works attributed to Plautilla has risen from three to twenty, meaning that other undiscovered masterpieces could be lying in wait.

Female-Led Museum Exhibitions

Last year, the Prado Museum in Madrid hosted an exhibition featuring two overlooked Baroque painters, Sofonisba Anguissola and Lavinia Fontana, in an exhibition entitled “A Tale of Two Women Painters.” Meanwhile, the National Gallery in London hosted a show dedicated to Artemisia Gentileschi. Notably, Sofonisba, Lavinia and Artemisia all achieved fame and renown during their lifetimes, including royal commissions, only to be eclipsed for centuries after their deaths. Sofonisba was particularly sought after for her ability to capture the expressiveness of children and adolescents in intimate portraits, while Lavinia’s commissions displayed a more formal Mannerist style. Artemisia, the subject of the National Gallery’s first major solo show dedicated to the artist, is recognized as much for the strength of her figures in chiaroscuro as for her life story involving sexual assault and trial by torture. Despite considerable difficulties, Artemisia was able to succeed in a male-dominated field and created over 60 works, most of which feature women in positions of power. Artemisia is now hailed as one of the most important painters of her generation and an established Old Mistress in her own right.

Female Artists at Auction

Artemisia Gentileschi’s Lucretia (ca. 1630-1640)

Despite their long slumber in the annals of history, these artists are not only receiving attention in museums, but in auctions as well. In 2019, a painting by Artemisia depicting Roman noblewoman Lucretia shattered records when it sold for more than six times its estimated price at Artcurial in Paris. While estimates originally placed the work at $770,000 to $1 million, the painting was ultimately acquired by a private collector for $6.1 million. Lucretia was discovered in a private art collection in Lyon after remaining unrecognized for 40 years. It was in an “exceptional” state of conservation according to Eric Turquin, an art expert specializing in Old Master paintings previously at Sotheby’s.

The earlier record for one of Artemisia’s works had been set in 2017, when a painting depicting Saint Catherine sold for $3.6 million. That painting, a self-portrait of the artist, was then acquired by the National Gallery in London for $4.7 million in 2018. This was the first painting by a female artist acquired by the National Gallery since 1991, and the 21st such item in its entire collection, which encompasses thousands of objects. Saint Catherine had been owned by a French family for decades, but its authorship was obscured prior to its rediscovery and sale by auctioneer Christophe Joron-Derem. The painting was acquired by the Boudeville family in the 1930s, but the exact circumstances of this acquisition and the painting’s prior whereabouts were unclear. At the time of the National Gallery’s purchase, museum trustees raised concerns that the work might have been looted during World War II, although there is no firm evidence to support this suspicion. Despite the gaps in the works’ provenance, it was ultimately determined that the painting had been with the family for several generations and Saint Catherine was welcomed to her new home in London.

Recent Attributions

Artemisia Gentileschi, David and Goliath (Courtesy of Simon Gillespie Studio)

More recently, a painting of David and Goliath was attributed to Artemisia after a conservation studio in London removed layers of dirt, varnish and overpainting to reveal her signature on David’s sword. While the work’s attribution occurred too late for inclusion in the National Gallery exhibition, the owner is apparently delighted to discover the work’s true author and is keen to loan it to an art institution so the public can enjoy the work. This painting was originally acquired at auction for $113,000 and may have been owned by King Charles I – quite an esteemed pedigree and sure to raise its value by a considerable amount.

In contrast to Artemisia’s ascendance, a painting once attributed to her father Orazio Gentileschi is now embroiled in controversy. That painting, which also depicts David and Goliath and described as “stunning” by the Artemisia show curator, has links to notorious French dealer Giuliano Ruffini. Ruffini is the subject of an arrest warrant due to his connection with a high-profile Old Master forgery ring operating in Europe. It is believed that the forgery ring, uncovered in 2016, garnered $255 million in sales, including works represented as being by Lucas Cranach the Elder and Parmigianino. Although these paintings were widely accepted as genuine masterpieces and fooled leading specialists, they did not have verifiable provenances. The paintings were said to belong to private collector André Borie, although that was not the case and Sotheby’s was forced to refund money to buyers once the fraud came to light. The Gentileschi in question had been “discovered” in 2012 and sold to a private collector, who loaned it to the National Gallery in London. At that time, the painting was praised for its “remarkable” lapis lazuli background, but the museum did not conduct a technical analysis before displaying the piece. Despite several warning signs – the painting’s recent entrance into the art market, its unusual material, its similarity to another Gentileschi painting held in Berlin, and the lack of published provenance – the museum stated that there were “no obvious reasons to doubt” the painting’s attribution.

The forgotten nature of some female artists demonstrates that their talents are not rare, but rather that they lack the opportunities and publicity that male artists often take for granted. Once their talent is amplified, female artists are capable of great things. This pattern continues today.

The Modern Struggles of Female Artists

As famous female artists lost to history capture the public eye, they are joined by female contemporaries who share a similar struggle against underrepresentation. Women’s contribution to modern and contemporary art is often exemplified by those with ties to established male artists: Mary Cassatt (who achieved recognition as an Impressionist in Paris through her relationship with Edgar Degas); Georgia O’Keeffe (who entered the public eye via her relationship to Alfred Stieglitz); and Frida Kahlo (introduced to the art world by her husband, Diego Rivera). This truncated view ignores the vast amount of creative output generated by women, and reinforces the notion that recognition must be made through a male lens, a view prevalent during Artemisia’s time. It is worth noting that Artemisia’s father Orazio Gentileschi was her teacher and facilitator in the Baroque art market. In fact, this attitude has denied countless female artists of their deserving places in the canon of art history. It has even enabled surreptitious artists to take credit for works by others.

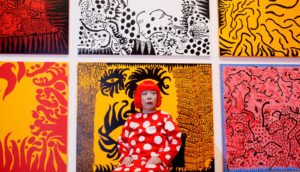

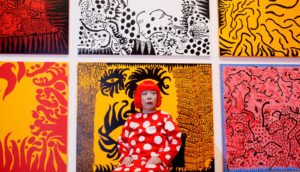

Yayoi Kusama (Courtesy: Kirsty Wigglesworth AP/Shutterstock.com)

Today, Yayoi Kusama is a household name. The world’s top-selling female artist, she is renowned for her peculiar polka-dotted paintings and sculptures, which command long lines at preeminent art institutions across the globe. Like many famous contemporary artists from the last century, she is strongly associated with a unique personal style, and recognized by her bright-red wig. Despite her phenomenal success, her position in the pantheon of notable contemporary artists was anything but assured. Born in the rural town of Matsumoto, Japan in 1929, Kusama was discouraged from pursuing a career; rather, she was encouraged to marry and start a family. Frustrated by the constant efforts to suppress her artistic aspirations, she wrote to the already famous Frida Kahlo for advice. Kahlo warned that she would not find an easy career in the US, but nevertheless urged Kusama to make the trip and present her work to as many interested parties as possible.

Unsurprisingly, Kahlo’s advice was accurate. After traveling to New York, Kusama’s early work received praise from notable artists Donald Judd and Frank Stella, but it failed to achieve commercial success. Her work also attracted the attention of other renowned artists, who were able to channel ‘inspiration’ from Kusama’s work right back into the male-dominated New York art market. Sculptor Claes Oldenburg followed a fabric phallic couch created by Kusama with his own soft sculpture, receiving world acclaim. Andy Warhol repurposed her idea of repetitious use of the same image in a single exhibit for his Cow Wallpaper. Most blatantly, after exhibiting the world’s first mirrored room at the Castellane Gallery, Lucas Samaras exhibited his own mirrored exhibition at the Pace Gallery only months later. Needless to say, these artists did not credit Kusama for her work and originality. This ultimately caused a despondent Kusama to abandon New York and return to Japan.

Kusama spent the next several decades largely in obscurity. The frustrations in her career resulted in multiple suicide attempts and long-term hospitalizations. However, Kusama always found a way to channel this energy back into her art, and she continued to create art in various formats as a way to heal. It was not until a 1989 retrospective of her work in New York and an exhibition at the 1993 Venice Biennale that the world truly tok notice of her work. This global reintroduction was enough to galvanize interest in her artistic creation, leading to the success she enjoys today. While it may seem just that such a talented artist would eventually receive recognition for her work, this is not always a given and Kusama’s near erasure from the art world should not be discounted.

The Gendered Art Market Divide

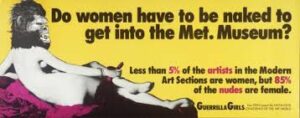

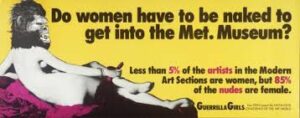

In today’s art market, artists, collectors, dealers, and museums are making a concerted effort to fight this type of erasure. Kusama stands as a beacon to others, demonstrating that female artists can reach the pinnacle of their profession. However, it remains an arduous career path for many. Statistical analysis confirms that female artists are underpaid and underrepresented in both the primary and secondary art markets. For example, compare the highest price paid for a work by a living artist by gender: Jeff Koons’ Rabbit sold for $91.1 million in 2019; while Jenny Saville’s Propped sold for $12.5 million that same year, a mere 14% of the Koons’ price. Some of this disparity can be explained by the difference between men and women’s treatment in the workplace generally, but the art world is also subject to a number of particularities. Attributed to a host of causes, perhaps none is more prominent than women’s almost total exclusion from studio art until the 1870s. The art world has existed in this environment for so long that its institutions and relationships now mechanically reinforce the disparity between genders: women are less likely to receive recognition and training, and buyers are less interested in art created by females. The interest in female-made art is also disproportionality concentrated on its biggest names; the top five best-selling women in art held 40% of the market for works by women auctioned between 2008 and 2019. It has become a self-sustaining cycle that can only be broken through deliberate and effective action.

Initiatives Supporting Female Artists

Artists and galleries have been working to shine a light on the current landscape of inequality in the market. Groups like the Guerilla Girls have used their cultural status and notoriety to vocalize issues regarding sexism, racism, and other types of discrimination still rampant today. This type of radical-meets-reformer message resonates with a newer generation that is more vocal about addressing discrimination, and frustrated by the seemingly lackluster efforts to minimize their impact on society. In honor of Women’s History Month, several galleries have announced shows dedicated to addressing some of these issues. The Equity Gallery is presenting “FemiNest,” a collection of works by female artists centered around the literal and metaphorical ideas conjured by the idea of a “nest.” The show explores in sculpture, textiles, painting and other media the new spaces that have opened for women in recent decades and their practical and spiritual impact for women. The Brooklyn Museum has announced a retrospective of Marilyn Minter’s work titled “Pretty/Dirty” aimed at challenging traditional notions of feminine beauty. Featuring more than three decades of work, the show will track Minter’s progress throughout the 1970s, 80s, and 90s. The show is also part of a larger series of ten exhibitions by the Brooklyn Museum dedicated to the subject: “A Year of Yes: Reimagining Feminism at the Brooklyn Museum.” Lastly, the Zimmerli Art Museum will feature an exhibition of works by the Guerilla Girls and other female artists who have worked to depict women’s unequal treatment in the art world, “Guerrilla (And Other) Girls: Art/Activism/Attitude.” (For more information about these shows and others addressing similar issues, see here.)

Although artists and art institutions have just begun the work of winding back centuries of discrimination, there is evidence that their work is already affecting the market. The percentage of female-generated artwork in the secondary market is increasing from year to year; from 2008 to 2018, the market more than doubled from $230 million to $595 million. Similarly, representation of women at major art shows is steadily, if inconsistently, increasing as well. This subtle shift in the market has been attributed at least in part to a new class of art purchaser: independently wealthy women, whose capital is self-made rather than inherited or shared via marriage. This novel source of demand is less sensitive to the traditional pressures of the market and is helping to fuel demand for works by female artists. Women’s History Month is an opportunity to reflect on the tremendous progress made by remarkable individuals in the art world, and to also contemplate the ripe opportunities that still lie ahead.

At Amineddoleh & Associates LLC, we are proud to have an inclusive team that represent a diverse roster of clients, including female artists, dealers, collectors, and businesswomen.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Feb 26, 2021 |

Leila will be presenting a free lecture for the Society of Art Law at the University of Oxford at 2:00 pm EST on March 3, 2021. “The International Repatriation of Antiquities” will examine a number of cultural heritage disputes and provide audience members with an opportunity to ask questions about art and cultural heritage law. The Zoom link is available HERE.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Feb 9, 2021 |

Amineddoleh & Associates LLC is proud to announce that an article by our associate Claudia Quinones has been published in the most recent issue of the Santander Art and Culture Law Review (SAACLR). The article, titled What’s In a Name? Museums in the Post-Digital Age, explores the evolution of museums according to new technological developments and an expansive view of these institutions’ social roles. It analyzes the International Council of Museums (ICOM)’s proposed definition of the term “museum” to provide a framework for discussion, then examines how rapid changes in the art market and the COVID-19 pandemic have exposed weaknesses in the current institutional system. Ultimately, the article argues in favor of a broader conception of museums, taking into account the needs of an evolving and diverse society.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Feb 1, 2021 |

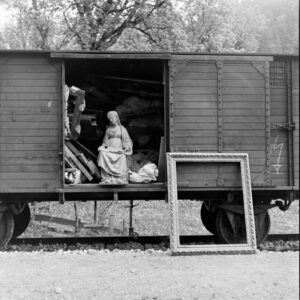

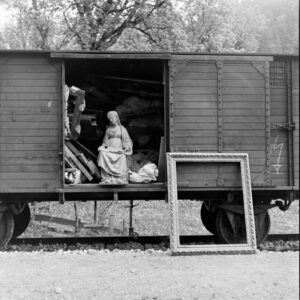

View of a train boxcar with an art collection looted by the Nazis, near Berchtesgaden, Germany, 1945. (Photo: William Vandivert/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images)

It has been estimated that the Nazi Party looted 20% of all art in Europe. The Nazis not only confiscated and stole property, but also forced victims to sell items at a fraction of their worth, pay exorbitant flight taxes, or abandon their homes and property when fleeing from the Third Reich. The toll of deprivation on such a massive scale is still felt many decades later. In recent years, multi-million dollar restitutions and disputes over valuable works have drawn interest from the international community. (Information about some of the landmark cases in this area can be found in an earlier entry in our Provenance Series.) One famous instance was the 2013 discovery of 1,500 works in a Munich flat belonging to Cornelius Gurlitt, the son of a notorious art dealer employed by the Third Reich. His infamous collection included works by artists such as Picasso, Monet, Matisse, and Chagall, some of them stolen. To date, the German government has identified only 14 works from the Gurlitt trove as definitively looted. Some of them have been returned to rightful heirs, purportedly signaling Germany’s “lasting commitment” to the repatriation of Nazi loot.

Over the years, Nazi-looted artwork has also made its way to other continents. One of the best-known legal battles concerning Nazi plundered art, Republic of Austria v. Altmann, 541 U.S. 677 (2004), was featured in the Hollywood film The Woman in Gold. The movie traced the provenance and legal battle for ownership of a collection of works by Austrian Painter Gustav Klimt, including a gilded portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer. The case made its way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, which led to the dispute being arbitrated in Austria. Five of the six valuable works in question were returned to the rightful owners, the heirs of the original owner. This year, the U.S. Supreme Court is poised to make a decision concerning the disposition of a valuable collection of medieval objects known as the Guelph Treasure. Far from being relegated to the past, the shadow of the Third Reich continues to haunt people across the globe more than 75 years after WWII came to an end.

The lack of a centralized authority or a uniform approach to restitution cases is an additional hurdle. In order to address the particular issues relating to Nazi-confiscated art, a series of forty-four non-binding principles known as the Washington Principles were developed in 1998. The Principles were drafted after the scale and severity of Nazi plunder became known to the public, partly due to previously private records released after the end of the Cold War. They have since been a useful tool for the return of looted property, based upon moral and ethical concerns. However, their non-binding nature means that voluntary cooperation is crucial for their implementation. Enforcement of the Washington Principles thus relies on public pressure and moral appeals rather than a strict duty to act. This can cause friction or a stalemate when the current possessors of Nazi-looted property do not wish to return items or compensate the heirs of the families from which the items were taken.

NAZI LOOTING BEYOND FINE ART

A Lódz ghetto official registers violins brought to the ghetto bank. The violins were shipped to Germany

Photo: From the archives of Yivo Institute for Jewish Research, New York

Nazi plunder was not limited to fine art. The Nazis also looted movable objects such as gold, silver, currency, musical instruments, religious items, furniture, books, ceramics, household items, photos, and countless personal effects. These items are not publicized as often because their values are generally not as high. However, these objects are often more susceptible to theft and subsequent sales, partly because they are difficult to trace, making recovery elusive. The Lost Music Project has dedicated themselves to conducting research on musical material lost during the Nazi era, and filling in the gaps for looted, confiscated, and displaced items. According to newly declassified documents, the Nazis deliberately targeted musical instruments belonging to Jewish owners. Priceless violins, including those by master craftsman Antonio Stradivari, were among the myriad of confiscated items.

The German documents obtained by the Chicago Tribune relate how Nazi forces were accompanied by musicologists, forming a Special Task Force for Music. The music experts carefully evaluated, catalogued, and prepared the best stolen instruments and other musical items for transport. This process took place under direct orders from Adolf Hitler himself, to obtain the instruments of highest artistic value for immediate relocation to Berlin. The campaign ran for five years, beginning in 1940, and was integrated into the war effort. For instance, bands playing looted instruments would welcome crews from Nazi submarines. There is a single surviving copy of an inventory list detailing the finest stolen instruments that had been confiscated, which mentions 75 antique stringed instruments, or “casualties of war.” Thousands of pianos were also stolen, and the vast majority of these are still unclaimed or at large.

Identifying and recovering looted musical instruments is no easy feat. Smaller instruments which are portable by nature, such as violins, are relatively easy to remove and hide. Furthermore, the international rare instrument trade has typically operated under limited public scrutiny, and dealers have sometimes failed to make thorough provenance checks before reselling items. Instruments are more difficult to identify than works of art, and documentation such as bills of sale or certificates of authenticity are not always available. Likewise, personal correspondence and photographs are rare. Carla Shapreau at the Lost Music Project has spent the last decade tracking down Nazi-looted instruments. She states that it is extremely challenging to find stolen instruments due to the fact that available documentation is both scarce and scattered across many countries. Such information has generally been inaccessible until recently, further muddying the waters. As additional plundered instruments come to light, unpleasant questions must be asked before restitution can take place. While the issue is gaining traction in the public sphere, reckoning with the past is not always straightforward, as demonstrated by the case discussed below.

THE FIRST DISPUTE OVER A MUSICAL INSTRUMENT

Illustration in book about Casa Guarneri (1906)

Fittingly, the first dispute over a Nazi-looted musical instrument arose in Germany. At the center of the case is a 300-year old violin crafted by Cremonese master Giuseppe Giovanni Battista Guarneri (better known as Giuseppe ‘filius Andreae’ Guarneri) purchased by Jewish music supply dealer Felix Hildesheimer from Hamma & Co. in Stuttgart, Germany in 1938. Its whereabouts prior to that date are currently unknown, although Guarneri violins have a fascinating history. Instruments bearing the Guarneri name are considered as precious as those by Antonio Stradivari, and valued at millions of dollars. Compared to Stradivari violins, which perform best in higher ranges, Guarneri violins are prized by musicians for delivering a deeper, more robust sound. This is attributed, in part, to innovations introduced by Giuseppe after he inherited his father’s renowned violin business in 1698. Not content to merely follow his father’s designs, his use of rounded upper bouts and tilted f-holes denote originality to complement his master craftsmanship. Although highly regarded today, Giuseppe’s life was spent in the shadow of Stradivari; where Stradivari patrons included kings and dukes, Guarneri violins were sold locally to practicing musicians. This contrast was made all the more apparent as both luthiers sold their creations from the Piazza San Domenico in Cremona, Italy. Giuseppe’s willingness to innovate, however, imbued his violins with full arch and a carrying power not seen in Stradivari’s work for another 20 years.

These violins are not only functional, but beautiful as well as historically and culturally significant. Like many such cases, the core of the recent Guarnieri violin dispute touches upon both non-legal and legal issues concerning ownership and provenance. Shortly after Hildesheimer purchased the violin, he was forced to sell his home and music store. He would eventually take his own life in 1939, survived by his wife and daughters who emigrated abroad to start over.

Tragically, stories like Hildesheimer’s were common during the reign of the Third Reich. They demonstrate a concerted effort to deprive Jewish victims of property under false pretenses. Despite these efforts, diligent research has made it possible to trace the path of the violin following the purported forced sale. The violin effectively disappeared for over 30 years. Then in 1974 it was rediscovered in disrepair in a shop in Cologne, Germany by violinist Sophie Hagemann. Unaware of its troubled history, it is serendipitous that Hagemann then used the violin as part of the music group Duo Modern to play music labeled as “degenerate” and banned during the Nazi regime. The violin remained in Hagemann’s possession until her death in 2010, at which point it passed to the Franz Hofmann and Sophie Hagemann Foundation (Franz Hofmann, Hagemann’s husband, was a composer who died in 1945). The Foundation claims to have received the violin in poor condition, requiring restoration. Eight years ago, the violin was valued at $185,000. The Foundation also conducted an investigation into the violin’s provenance, recognizing that the gap in ownership between 1939 and 1974 was a source of concern. Ownership was eventually traced back to Hildesheimer, at which point the Foundation sought to “proactively clarify” any potential restitution claims by contacting Hildesheimer’s descendants. In spite of these early efforts to amicably resolve a potential dispute, interaction between the Foundation and the heirs became strained over time.

The German government’s Advisory Commission on the Return of Cultural Property Seized as a Result of Nazi Persecution was called to review the dispute in 2015. The Commission seeks to bring the Washington Principles into practice. It may be called upon to assist in the resolution of disputes concerning the return of cultural assets seized from their owners as a result of Nazi persecution. A request for intervention may be filed by a former owner, heirs, or institutions and individuals currently in possession of the relevant cultural asset. The Commission works toward amicable settlements between the parties, who must agree to enter into mediation. The Committee ultimately issues a non-binding recommendation. In 2016, the Commission determined that the violin had either been sold under duress or seized by the Nazis after Hildesheimer’s death. The panel recommended that the Foundation maintain possession of the instrument and pay $120,000 to the dealer’s descendants as compensation.

Both sides initially accepted the recommendation as a fair and equitable solution; however, the Foundation now refuses to comply. Although it first claimed that it could not raise the funds to meet the allotted amount, the Foundation issued a statement on January 21, 2021 challenging the Commission’s recommendation. According to the Foundation, new information suggests that the violin was not the subject of a forced sale, meaning that it was not looted by the Nazis and falls outside of the Commission’s scope. The Commission responded by issuing a public statement condemning the Foundation’s actions as “not just contravening existing principles on the restitution of Nazi-looted art… [but] also ignoring accepted facts about life in Nazi Germany.”

FORCED SALES

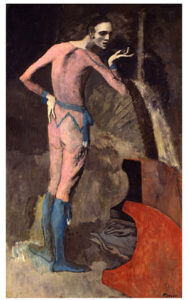

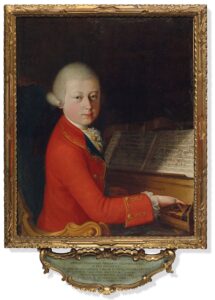

Picasso’s “The Actor.” Credit: Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ultimately, the Commission cannot compel the Foundation to honor its recommendation. Furthermore, the Foundation’s argument raises the question as to whether all sales made during the Nazi regime should be considered coerced or forced, or if there is the possibility that some transactions were voluntary. This topic has arisen in the past, recently in Zuckerman v. Metro. Museum of Art, 928 F.3d 186 (2nd Cir. 2019). Zuckerman raised issues about the definition of duress, and it was one of the first cases decided after the passage of the U.S. Holocaust Era Art Restitution (HEAR) Act of 2016. There, the great-grandniece of a German-Jewish art collector sought to recover a Picasso painting from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The plaintiffs alleged that the painting was sold under duress in 1938 when the owners fled Fascist Italy. The work was eventually donated to the Met in 1952 by a subsequent purchaser. The Southern District of N.Y. dismissed the case, ruling that the Leffmanns’ sale of the Picasso was not be considered a “forced sale” or made “under duress.” The plaintiffs appealed, but the Second Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed and dismissed the case on statute of limitations grounds. The court ruled that the plaintiffs had waited too long to file a complaint to recover a work that had been on public display (in one of the world’s most visited museums) for decades. As such, the court did not provide a definitive answer as to what comprises a forced sale or sale under duress.

Like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Zuckerman, the Foundation claims there is no proof that the sale of the violin was made under duress. However, the Nazi Party was well-known for “persuading” Jewish citizens to hand over their property under the Nuremberg Laws. The timing of the violin’s disappearance is suspect. Unusually, the Foundation admitted that the provenance of the violin is incomplete, it took the initiative to contact Hildesheimer’s heirs, and it even requested intervention by the Commission. This seems to indicate the Foundation’s tacit acknowledgment that the movement of the violin is problematic or at least it requires heightened scrutiny. The sudden reversal of the Foundation’s attitude is surprising.

REFUSING TO COMPLY WITH RESTITUTION DETERMINATIONS

The Foundation’s refusal to comply with the Commission’s recommendation illustrates the inherent problem in relying on voluntary cooperation for restitution cases. In the absence of a legally binding decision, such as those issued in a court of law, parties may ignore determinations. Such open and notorious refusal to comply threatens the Commission’s status and could seriously undermine its ability to resolve similar disputes moving forward. In the words of Hildesheimer’s grandson, “If the commission can be defied with no consequences, I don’t see how these cases can be dealt with in [the] future.” Most institutions and private parties have been unwilling to risk the negative press that follows noncompliance with a Commission determination. If the Foundation can weather criticism without consequence, it could set an ignoble precedent and embolden similarly situated parties to defy the Commission. However, there is still time for the Foundation to change its tune, and political pressure or moral principles may sway the Foundation to implement the Commission’s recommendation and support Germany’s restitution policy.

Tracking down and recovering Nazi-looted art and objects is extremely challenging. Not only have countless items been lost, damaged, or destroyed without a trace, but musical instruments have their own lives and personalities, echoing their previous owners. In the words of the late Elan Steinberg, former executive director of the World Jewish Congress: “There is something more emotional and personal when you start to talk about items such as musical instruments… A bank account, an insurance policy – those are material assets. A violin was played by someone. So what we have involved here is not simply the stealing of property but the stealing of memories and humanity. In a very real sense, this is more brutal than financial theft. It’s about erasing identity.”

TROUBLES WITH NOTABLE INSTRUMENTS

Joseph Goebbels, presenting the gifted violin to Nejiko Suwa in 1943. Credit: Cegesoma Bruxelles

The story of another famous violin echoes many of the same challenges discussed above, despite the instrument having been subject to public scrutiny for over 50 years. In 1943, German Minister for Propaganda Joseph Goebbels gifted a Stradivari violin to a 23-year-old Japanese prodigy, Nejiko Suwa. Despite the Nazis’ prolific record keeping, it is unclear how Goebbels acquired the violin, leading many to suspect it was confiscated or purchased under duress. After returning to Japan with the violin, a contemporary critic openly challenged Ms. Suwa to “let decency as a human being overcome your love as an artist, shake off your tears, and make a firm decision to return this violin to the former owner on your own accord.” Ms. Suwa, who died in 2012, publicly contradicted any claims that the violin had been unethically sourced, arguing that it was legally purchased by Goebbels’ ministry. The absence of information about its previous owners is sadly not uncommon for instruments that passed through Nazi possession. Goebbels was known for equipping prominent musicians with master-crafted instruments, so long as they comported with Nazi standards of decency; plundered instruments would have provided an all too convenient means of sourcing these gifts. The use of instruments in this way highlights their cultural significance, and they were used to aid in Goebbels’ effort to alter the cultural fabric of Europe.

This particular gift would become inseparable from its new owner, as Ms. Suwa protected the violin as she moved across the war-torn continent. “I have risked my life to protect it,” she was quoted years later. After the Second World War, Ms. Suwa was the first Japanese musical star to perform in the U.S., participating in a benefit concert at the Hollywood Bowl. During the performance, she used her gifted violin to play Violin Concerto in E Minor by Mendelssohn, a composer who had been blacklisted during Nazi rule. The violin’s use for this repertoire sent a message about the Nazi’s cultural restrictions, but its continued possession by Ms. Suwa leaves a morally conflicted legacy. The violin is now held by Ms. Suwa’s nephew, who declined to discuss specifics about the future of the instrument. The lack of information about prior ownership and the absence of a more effective restitution effort leaves the fate of these precious and culturally important objects in question.

CHALLENGES POSED BY RESTITUTION CLAIMS

There are various challenges tied to the restitution of Nazi-looted art and objects. The lack of evidence or living witnesses, as well as the lack of proof concerning the circumstances of a sale or seizure that occurred decades ago, mean that definitively proving ownership is difficult. In some cases, heirs may not even be aware of their families’ previous collections or any viable legal claims they may possess, whether in the U.S. or abroad. Artworks not included in catalogues raisonnés or referenced in an artist’s biography or correspondence are especially difficult to trace. For instance, without references to their individual characteristics, Guarneri violins could be nearly impossible to distinguish from one another. Movable items, including musical instruments, jewelry, and furniture, may have been damaged, disassembled, covered with paint or varnish, or otherwise modified after their last known appearance. Under this camouflage, Nazi plunder may be hiding in plain sight.

Nonetheless, while progress in recovering these items may be slow, ownership disputes continue. The Foundation’s posturing over compensation threatens the hard-won recommendations issued by the Commission and delays potential justice for the heirs of dispossessed Jewish families. As this is the first musical instrument case to come before the Commission, the precedent is troubling. We will follow the case with great interest in hopes that a fair and just solution may be found.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jan 27, 2021 |

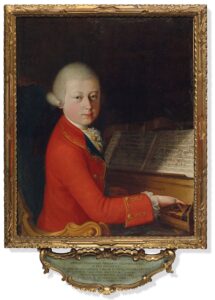

Mozart’s manuscript that sold at Sotheby’s for $413,000 in 2019.

Today we celebrate the 265th anniversary of the birth of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart with a special entry in our provenance series. Centuries after his birth, Mozart continues to dazzle the public imagination through reinterpretations of his work, including The Magic Flute by Julie Taymor, Academy Award-winning film Amadeus, and the Amazon Prime series Mozart in the Jungle. As the works of a musical prodigy and globally-recognized composer, Mozart’s manuscripts are highly prized by collectors. One such piece, an original score with two minuets dating from 1772, sold for $413,000 (€372,500) at auction in 2019. Notably, Mozart was only 16-years-old when he created the works. The first versions of Mozart’s scores are significant because, unlike Beethoven, the young composer did not make major revisions to his drafts. This means that there are fewer copies in existence, making them both rare and valuable. Indeed, the final hammer price for this piece exceeded the projected value by nearly double.

The minuet score has an esteemed provenance; it was originally kept by Mozart’s sister Nannerl (who was an accomplished musician and composer herself), and ultimately entered the collection of Austrian writer Stefan Zweig. Upon Zweig’s death in 1986, his collection of manuscripts, including Mozart’s handwritten catalogue of works, was donated to the British Museum. The score was later acquired by Swiss bibliophile Jean-François Chaponniere, making it the only copy of an autograph composition by Mozart in private hands. Moreover, this is the only surviving copy of this particular composition in manuscript form. The other manuscripts in this minuet series are currently held by the US Library of Congress and the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, Austria.

However, Mozart’s manuscripts were already setting records prior to the 2019 auction. In 1987, a private collector paid $4.4 million for a 508-page compendium of Mozart’s scores, which was the highest amount paid for a post-medieval manuscript at the time. To compare, the previous record for a musical manuscript was $544,500 for an incomplete copy of Igor Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring” in 1982. The 1987 record was later surpassed in 2016, when a handwritten score of Gustav Mahler’s Second Symphony was auctioned for $5.6 million. Although the value of classical music compositions has risen sharply in the past few decades, this phenomenon is not free from controversy. A score attributed to Beethoven failed to sell at Sotheby’s when scholars questioned the authenticity of the work. This demonstrates the importance of establishing provenance for all types of collectible items, even those tied to musical geniuses. Fortunately, the minuet score posed no such problems, making it a true prize.

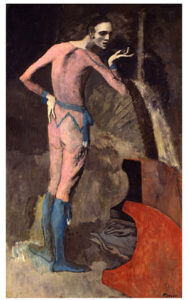

Sold for $4.4 million, the portrait of the teenage Mozart has an alluring provenance.

But private collectors’ interest in Mozart is not limited to musical manuscripts; a rare portrait of the composer as a teenager fetched €4,031,500 at auction soon after the minuet score was sold in 2019. The painting has an impeccable provenance, as it was referenced in a letter from Mozart’s father Leopold to his wife Maria Anna, dated January 1770. In 1769, Mozart had toured Italy with his father. At the age of 13, he was already a celebrity recognized for his remarkable musical talent. During Mozart’s stay in Verona, a passionate music lover commissioned a portrait of the prodigy. This is one of only five confirmed portraits of the composer painted during his short life.

What is unusual for this painting, aside from its glimpse of the composer as a young man, is the thorough documentation of the circumstances leading to its creation. Pietro Lugiati, Receiver-General for the Venetian Republic and member of a powerful Veronese family, commissioned the work while hosting Mozart and his father in Italy. The portrait depicts the teenager in a powdered wig and red frock before a Renaissance harpsichord in Lugiati’s music room. By all accounts, Lugiati was so in awe of the young Mozart he described the child as a “miracle of nature in music” in a letter to the composer’s mother and essentially detained the Mozarts for two days, until the portrait was completed.

Curiously, despite the references to the painting in contemporaneous documents, the artist remains unconfirmed. While it is likely that the painter was leading Veronese artist Giambettino Cignaroli (he referenced Mozart’s visit to his studio), an alternative attribution is Saverio della Rosa, Cignaroli’s nephew. The painting could also have been a collaboration between the two artists. Although firm attribution remains elusive, the painting was an immediate success – one of the world’s oldest newspapers, La Gazzetta di Mantova, praised the work a mere five days after it was finished – a fitting tribute to a great musician.

The Mozarteum (the house where Mozart was born) in Salzburg, Austria is currently closed due to COVID. And it is not possible for most people to purchase original manuscripts of the musical prodigy, but we can celebrate the musical genius’ birthday by listening to one of over 600 musical compositions he wrote. Happy birthday Wolfgang!