by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Feb 18, 2022 |

Authenticating artwork can be a complex endeavor at the best of times. Because the value of artwork – both aesthetic and monetary – is subjective, it relies on a complex process involving authentication. In layman’s terms, authentication is ascertaining whether a work is original and can be attributed to a certain artist. However, when an authentication is questioned, this inevitably leads to disputes. There is no shortage of cases involving inauthentic artworks created by forgers (such as Wolfgang Beltracchi and Pei Shen Qian in the infamous Knoedler Gallery scandal), but a rather unique situation arises when artists themselves disavow their work. Can it still be considered authentic in such circumstances? Who is the rightful person to determine the authorship of a work – the themselves, a seller, a buyer, or an expert?

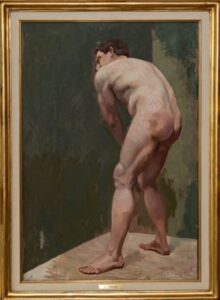

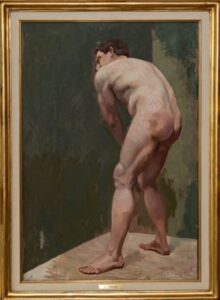

Standing Male Nude, by Lucian Freud

Photograph Courtesy of Thierry Navarro

Lucian Freud’s Standing Male Nude – A Case Study in Authentication and Disavowal

In the case of Lucian Freud, one of the leading English artists of the 20th century, his own denial of a painting was not considered conclusive enough to classify the work as inauthentic. In the mid 1990s, the painting, Standing Male Nude, was purchased by a Swiss art collector. The collector recalls that a few days later, he was contacted by Freud who wanted to repurchase Standing Male Nude, offering him double what he had paid. Upon the collector’s rejection of this offer, the artist became furious and said that unless the collector sold him the work, he would deny having painted it and leave the collector unable to sell. The Freud estate subsequently refused to authenticate the painting, and the collector’s piece languished in limbo for decades.

However, this past November, a team of art experts found definitive evidence confirming what the artist had denied: the painting was, in fact, an original Freud. Scientific tests involved taking pigment samples and using infrared imaging to compare Standing Male Nude with other authentic works by the artist. The work was found to have “an absence of negative indicators for [Freud’s] authorship” by a leading British expert, Dr. Nicholas Eastaugh. These findings were supported by groundbreaking AI technology used by Dr. Carina Popovici at Swiss company Art Recognition. As a result of their own research into the work’s provenance, the collector and private investigator Thierry Navarro believe that the painting was a self-portrait and that Freud was embarrassed by the nude of himself. Although the figure in the portrait is viewed from behind, the facial features appear to match photographs of Freud. Prior to the collector’s acquisition, the painting had hung in a Geneva flat used by fellow artist Francis Bacon at a time when the city served as a “bubble” for the gay community. This helps explain why Freud was so intent on recovering the work.

By creating an authenticity question, the painting’s marketability and resale value was sharply limited. Only works with certificates of authenticity or similar guarantees by living artists will fetch high prices on the legitimate market. Freud’s paintings are worth millions – a lifesize nude of his muse Sue Tilley sold in 2015 for £35.8 million at Christie’s. Previously, another portrait of Sue sold in 2008 for $33.6 million, setting a record at the time for any living artist.

Essentially, authentication can “make or break” the worth of a painting because its attribution is critical. As more and more people view art as an investment and separate asset class, authenticity goes to the core of how the art market operates. But this is not a new phenomenon.

Hahn v. Duveen: The Authentication Case that Rocked the Art World

In 1920, legal disputes concerning art gained worldwide attention when the owner of a painting, believed to be by Leonardo Da Vinci, sued an art dealer who questioned the authenticity of the subject artwork. Dealer Joseph Duveen was one of the world’s best known and successful dealers. Although Duveen had never seen the painting or examined it in person before rendering his opinion, he reasoned that the painting in dispute could not be authentic because the genuine version of the work was in the Louvre. His statement made the painting worthless and unsellable due to the dealer’s sway over other collectors. This case, Hahn v. Duveen, was described as “the world’s most celebrated case of art litigation – a hearsay case with a picture as defendant.” In particular, Duveen was sued for libel; a legal claim that requires the substance of a statement to be false and made with malice.

Clipping from The Illustrated London News of La Belle Ferronière, July 18, 1931 from a Duveen Brothers scrapbook

The court’s opinion criticized the art market and the authentication process: “[a]n expert is no better than his knowledge. His opinion is taken or rejected because he knows or does not know more than one who has not studied a particular subject. . . . Because a man claims to be an expert, that does not make him one.” Hahn v. Duveen, 234 N.Y.S. 185, 190 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1929). Nonetheless, the hold of connoisseurs like Duveen is not so easily dispelled. The market relies heavily on subjectivity when assigning value to works. What makes one artist more valuable than another is not a straightforward matter, and courts in New York (the heart of the global art market) have consistently declined to regulate how the market operates, arguing that it is a matter for participants and experts to decide, as they have the required specialized knowledge. Whether this “hands off” approach is appropriate or not is a question for another day, but it is worth noting that the parties in Hahn v. Duveen settled out of court without a firm attribution in place. Decades later though, Duveen was vindicated when the work sold as a “copy” for $1.5 million in 2011 (likely due to the work’s fame as a result of the litigation).

The situation becomes even more complicated when the person refuting the authenticity of a work is the artist, and not merely someone who “studied a particular work.” How does authentication come into play at such a time?

Authentication as a Three-Legged Stool

In the art market, authentication is often compared to a three-legged stool, which relies on three prongs: forensics, provenance, and connoisseurship. (1) Forensics relies on ever-developing technology to run a myriad of scientific tests on the work. These tests determine certain physical attributes of the painting that can lead to a conclusion supporting its authenticity. However, forgers are also aware of the tests that are run on these works and are able to avoid detection by employing creative methods, such as artificially aging works or using the same pigments as the original artists. (2) Provenance looks at historical evidence tracing the ownership of the work. Ideally, the history of the work can be traced back to the artist without any gaps. (3) The final prong relies on connoisseurs who use their expertise and judgment to determine whether they believe that a work is authentic. This type of evaluation, also known as stylistic analysis, relies on the expert’s “eye” to recognize the artist’s unique style, including the subject matter, brushwork, choice of colors, and composition.

Authentication is established by balancing these three prongs. However, courts, as compared to the art market, tend to weigh these prongs differently. Court prefers the more concrete prongs of forensics and provenance research, whereas the market tends to rely upon connoisseurship. This may cause tension as a court can determine that a work is authentic by weighing the persuasiveness of expert credentials and testimony, but this will not necessarily be reflected in the market. In Greenberg Gallery, Inc. v. Bauman, 817 F.Supp. 167 (D.D.C. 1993), the court sided with plaintiff’s expert Linda Silverman in holding that a mobile sculpture, titled Rio Nero, was an authentic work by Calder, even though Klaus Perls, a renowned Calder expert, identified it as a copy. The court noted that as a trier of fact, it relied on a preponderance of the evidence. However, the art market operates in a very different manner and Perls’ opinion was seen as definitive. The mobile remained unsold for years.

A Lack of Definitive Answers: The Pollock Dilemma

Given that none of these three prongs provide conclusive results, each analysis may lead to contradicting conclusions. As a result,

Jackson Pollock painting. in his studio

Photo by Martha Holmes/The LIFE Premium Collection/Getty Images

many experts may disagree on the attribution of a work. For example, in 2013, the three prongs left the authenticity of a Jackson Pollock unclear. The work in question, a painting titled Red, Black & Silver, was allegedly created by Pollock for his lover Ruth Kligman. The artist’s widow, Lee Krasner, and the Pollock-Krasner Authentication Board disputed the claim. After Kligman’s death, her estate attempted to sell the work at auction in 2012, but it was withdrawn by Phillips so that further research could be performed.

The forensic evidence suggested that the work was done by Pollock. Scientific analysis found a polar bear hair embedded in the painting, which suggested that the painting was authentic since Pollock had a polar bear rug in his studio in 1956, and he was known to lay the paintings on the floor. But the provenance was less cer

tain. While a clear chain of ownership was identified, there was no historical documentation to verify this claim. Lastly, connoisseur Francis V. O’Connor stated that the work does not look like a Pollock. He opines that even if the work was made on Pollock’s estate, it wasn’t necessarily by Pollock’s hand. In this case, as in many others, the three prongs of the ‘three-legged stool’ analysis have resulted in an inconclusive determination as to the authenticity of a work. As a result, this work remains in limbo.

Protecting Expert Opinions: A Legal or Market Concern?

The lack of certainty in the authentication process has led many art experts to hesitate when offering opinions about authenticity. In many instances, art experts have provided their opinions, and their opinions have subsequently been proven wrong. When an art owner is harmed by the opinion of an expert, that owner may decide to sue. This has led many art experts to be hesitant to provide their opinions for fear of facing litigation. As a result, there are fewer connoisseurs providing opinions, thus resulting in a decline in the quality of connoisseurship.

Legal actions taken against authentication boards and experts affect the art market. In Thorne v. Alexander & Louise Calder Foundation, 70 A.D.3d 88 (1st Dept. 2009), the plaintiff sued the Calder Foundation because it declined to authenticate two theatrical stage sets and related materials designed by the artist. The court found that there was no legal basis to compel the foundation to issue an authenticity opinion, even though it would impact the sale price. The Andy Warhol Foundation has also faced its share of lawsuits, with Simon Wheelan v. The Andy Warhol Foundation, 2009 WL 1457177 (SDNY 2009) alleging that the foundation strategically refused to authenticate certain works to drive up the value of others and monopolize the market. While this case was ultimately withdrawn, it calls into question how experts are regulated to ensure good faith when issuing opinions.

Experts can face liability for incorrect opinions, even those given in good faith, under the theory of tort negligence, in addition to legal costs associated with defending themselves. A flurry of lawsuits culminated with Keith Haring Foundation disbanding its Authentication Committee in 2012. As a result, authenticators are not providing opinions, which is negatively affecting the art market. In response, a bill was introduced in the New York State Legislature in the spring of 2014. This bill, which would amend the New York Arts and Cultural Affairs Law, would protect art authenticators from “frivo

lous or malicious suits brought by art owners.” Authenticators are defined as individuals and entities “recognized in the visual arts community as having expertise regarding the artist” when rendering an opinion. A modified version of the bill was passed in 2015, but it remains to be seen whether this will provide a robust shield for art experts issuing authenticity opinions.

Moral Rights Legislation – a Shield or a Sword for Artists?

In many instances, artists are victims of the art market’s subjectivity when determining authenticity. For example, in Herstand Co. v. Gallery, 211 A.D.2d 77, (N.Y. App. Div. 1995), Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, a Polish-French modern artist known as Balthus, declared and signed that a drawing was not authentic. Despite Balthus’ confirmation, the court ruled in favor of the gallery selling the artwork, choosing to believe an expert’s testimony of authenticity over the artist’s own actions.

However, visual artists possess legal rights that can protect them and their works. Most countries have a moral rights system allowing an artist to protect their personal and reputational rights, in addition to their economic rights (such as copyright). For example, many countries grant artists the right to not have a work falsely attributed to them and to protect their honor and reputation with respect to their works.

In the United States, some of these rights have been codified in the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA). VARA is more limited than international art law, or the moral rights of other countries, such as France. Under VARA, an artist’s rights are limited to their lifetime and cannot be assigned or transferred. But VARA grants artists two overarching rights with respect to their authorship. First, artists have a right of attribution, so that an artist is recognized for works they create and are not associated with those that they did not create. Second, artists have a right of integrity to protect their reputation, such that they can disavow works that have been damaged, altered, or mutilated.

However, as seen in the case of Freud’s rejection of Standing Male Nude, artists can also create uncertainty and manipulate the authentication of their works for their own personal reasons.

Cowboys Milking, 1990, Cady Noland

Another artist, Cady Noland, disowned her work, rather than rejecting it outright. This occurred with two different works that were damaged or not properly stored and preserved. Her 1990 silkscreen on aluminum, Cowboys Milking, went up for auction at Sotheby’s but upon Noland’s inspection, she noticed that the corners of the aluminum were damaged. Similarly, Janssen Gallery stored Noland’s sculpture, Log Cabin (1990), improperly and the gallery restored the work without Noland’s consent. In each instance, Noland disowned the work, arguing that if the work were to be auctioned off with her name attached, it would prejudice her honor and reputation. Noland’s rejection of two sculptures spurred lawsuits from the owners, who were no longer able to sell the works for their full value.

Elyn Zimmerman, known for her large scale art sculpture installations, also rejected two projects from her list of works. In one instance, the work was not installed consistent with her design, and the contractor left a large hole in the sculpture. Zimmerman said that the work was past salvaging, and so decided not to put her name on the piece. Both Zimmerman and Noland exemplify ways in which some artists rely upon their reputational rights to remove any unwanted attributions.

Other artists simply reject any association with works so that they can assert control over their oeuvre.

Richard Prince is well-known today for his appropriations of advertisements and other popular images. However, before he gained acclaim in the 1980s, he had explored a variety of different mediums including paintings, drawings, collages, and etchings. In a 1988 interview with Flash Art magazine, Prince said he destroyed 500 of his early works. Prince said that he ripped up the works that he did not like from the mid to late 1970s and put them in garbage bags. However, several works from that period were already sold and were beyond his reach. Prince has claimed that these works no longer represent him as an artist. Over the years, Prince has taken several steps to disavow his early work and re-create his oeuvre beginning in the 1980s. On Prince’s website, his biography omits any exhibitions of his work before 1980, creating the public impression that his career began in that year. He also relied upon the copyright to his art, refusing any reproductions of these early works to be printed in books or catalogues. When a museum exhibited his early work, he refused to participate or grant the museum any rights for images or reproduction. Generally, major museums have followed Prince’s example; both the Guggenheim and Whitney Museums have only acknowledged and exhibited works from or after 1980 in their retrospectives of Prince.

Gerhard Richter in his studio with his paintings on the wall, February 1962.

Copyright and Photo by: Gerhard Richter 2020 Courtesy of the artist and the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Gerhard Richter, a German artist whose works have sold for record prices, remains in strict control of his catalogue raisonné to this day. Over the years, Richter has become an artist known for revising and editing his oeuvre. He has removed works from catalogues and rejected paintings from his early West German period. During this period, between 1962 and 1968, Richter went through a stylistic evolution in which he experimented with a figurative style. These realistic paintings varied greatly from his later abstract and photo-realist paintings. Richter’s revisions of the historical catalogues has sparked controversy. As the artist and creator of the paintings, he has a right to define his own body of work. Yet, using this right to modify these historical catalogues can create disputes and distrust in their historical accuracy, and rejecting works offhand can manipulate the market and the resale of works disowned by the artist.

Another famous artist, Pablo Picasso, famously said “I often paint fakes.” This statement questions the art market and the authentication of works but also causes problems for buyers. This was also reflected when Picasso rejected a painting later confirmed to be his original work. When he was handed a photograph of Erotic Scene (La Douceur), he said it was not his work, but just a “bad joke by friends”. The painting, gifted to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1982, sat in storage for several decades. In 2010, the Met prepared for a Picasso show and was faced with authenticity issues concerning the work. The museum ultimately confirmed that the painting was authentic despite Picasso’s statement.

Pest Control Logo

Photo from Pest Control website

As the art market has developed and the complexity of authentication leads to legal controversy and disruption, living contemporary artists have taken authentication into their own hands. Banksy has put a system in place that allows him to be the only authority on the authenticity of his work. This control is in part a by-product of his anonymity. In 2008, Banksy established Pest Control to serve as the sole authenticator of his works. Any Banksy sold after 2009 will be accompanied by a certificate of authenticity (COA) issued by Pest Control and they will retroactively issue COAs for any pre-2008 works they deem authentic. Establishing a third-party authenticator like Pest Control protects the artist’s rights, but it can also influence the market. As seen above, the artist does not always have the final say in the authentication of their works. Pest Control, however, has allowed Banksy to do so. In 2008, five works came up for auction at Lyon & Turnbull in London, and Banksy refused to authenticate them. Pest Control rejected the works’ authenticity and encouraged buyers to boycott the sale. As a result, none of the works were sold. Pest Control has given Banksy access to the art market, allowing him to control what is included in his body of work and sell his work without interference from, or reliance upon, the uncertainty of the three authentication prongs.

As exemplified by Noland, Zimmerman, Prince, Richter, and Picasso, artists have moral rights, and some artists exercise them once their art is on the market. Some artists rely on these rights to protect their work and reputation, others use them to subvert the art market, while others simply wish to remove or disassociate themselves from works they feel are inferior or not representative of their artistic vision and image. While the protection of authors’ rights is important, some question whether artists are abusing their power without considering the larger effects on the market. On the other hand, it may be argued that as the creators of artistic works, artists are in the best position to determine what should or should not be included in their body of work. While this may cause consternation for collectors seeking to resell artworks, there may be limited recourse.

Conclusion

Authentication and attribution is a tricky business. Even after centuries of the art market operating in more or less the same way – responding to supply and demand as well as subjective appraisal – there is still no magic formula to establish whether a work is authentic. Forensic and scientific analysis, combined with a work’s provenance, may provide evidence in support of authentication, but in the absence of a clear link to the artist, collectors risk works being called into question at a later date. Even if an artist is alive at the time the work is sold, there is no guarantee that he or she will wish to remain associated with it. This is why artists and collectors, no matter how new or experienced, should consult with reputable legal counsel to be aware of their rights and risks when engaging in art transactions.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Feb 13, 2022 |

In honor of Valentine’s Day, the latest blog post in our Provenance Series centers on the stories of famous lovers and the art inspired by them.

Most people are familiar with playwright William Shakespeare’s famed star-crossed lovers, Romeo and Juliet. This pair from Verona has been immortalized in music, films, subsequent works of literature, and countless works of art. However, there are other ill-fated romantic couples that deserve to share the artistic spotlight.

Dante and Betrice by Henry Holiday

Dante Alighieri, widely credited as the father of modern Italian language, wrote his magnum opus in the 13th century after falling in love with a woman known as Beatrice. Dante admired her from a distance, having only met with Beatrice twice, the first time when they were both nine years old. These interactions moved him so profoundly that Beatrice is widely credited as Dante’s muse even though she was married to another man. Beatrice first appears in Dante’s autobiographical text La Vita Nuova, where she is portrayed as a courtly lady. Beatrice died in 1290. Dante then composed a three-volume narrative poem describing the author’s journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise, where he is eventually reunited with his lady love. This work, The Divine Comedy, is considered one of the great masterpieces of world literature and it was deeply inspired by Dante’s feelings for Beatrice. Indeed, Beatrice serves as the epitome of grace and beauty. She guides the pilgrim Dante into heaven, where his worldly love is transformed into divine love.

Paolo and Francesca da Rimini by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

While Dante and Beatrice meet a happy end in the spiritual realm, other couples in The Divine Comedy are not so fortunate. Paolo Malatesta and Francesca da Rimini were real-life contemporaries of Dante who make an appearance in Canto V of the Inferno. Francesca was the wife of Paolo’s brother, who killed them both in a rage after he discovered their secret union. As adulterous lovers, the pair is bonded together for eternity in a fiery whirlwind, symbolizing their uncontrollable lust. But it seems that Dante empathized with Paolo and Francesca’s plight; he wrote that they fell in love while reading medieval romances, particularly those depicting Lancelot and Guinevere (another doomed duo). Upon hearing this, Dante is overcome with pity and weeps for their fate. Despite only occupying 69 lines in Dante’s epic poem, this depiction influenced subsequent generations of artists, particularly the Romantics in the 19th century.

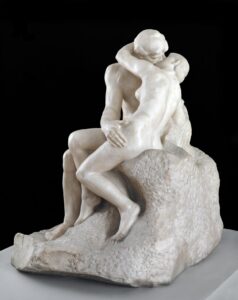

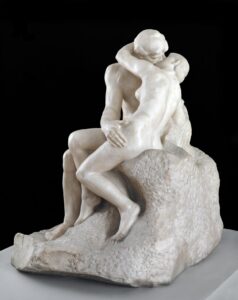

The Kiss, by Auguste Rodin

The poet’s own idealized yet bittersweet love was a favorite subject of the Pre-Raphaelite painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti, whose father was a Dantean scholar and who was in fact named after the Florentine poet. Rossetti used Elizabeth “Lizzie” Siddal and Jane Morris as models for Beatrice. In a case of life imitating art, Rossetti’s relationships with Siddal and Morris both ended unhappily. Rossetti painted Beata Beatrix after Siddal’s tragic death from an overdose of laudanum in 1862. The painting has various renditions, all placing the titular Beatrice (with Siddal’s characteristic red hair) in a beam of light, symbolizing her spiritual transfiguration. Later, Auguste Rodin’s famous 1880s sculpture “The Kiss” was originally titled “Francesca da Rimini.” The original pose was reportedly so passionate that it was censored at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair due to fears that it would incite “lewd behavior.” Rodin was eventually persuaded to change the monumental marble’s name. Yet Paolo and Francesca still appear in the bronze work “The Gates of Hell,” directly inspired by Dante’s Inferno.

Even 700 years after his death, Dante’s work remains highly prized. In 2017, three “tome-raiders” stole over £2 million worth of antiquarian books (over 160 items) from a London warehouse. The stolen property included a rare 1569 edition of The Divine Comedy. The thieves managed to evade the security system by entering the warehouse from above. They bored holes into the reinforced glass skylights and lowered themselves 40 feet on ropes, similar to the film Mission Impossible. The criminals likely received inside information on the location of the valuable books, leading to the heist. The international rare book market is worth approximately $500 million a year. Unfortunately, that means that thieves target valuable manuscripts for the illicit trade. Unfortunately, book theft has been on the rise. However, because of the notoriety of the stolen works, here the thieves’ options were to issue a ransom demand or attempt to sell the goods on the black market for a fraction of the price (5-10%). Fortunately, the books were recovered in Romania in 2020 before they were offered for sale. The crime was linked to various organized crime families with “a history of complex and large-scale high value thefts.”

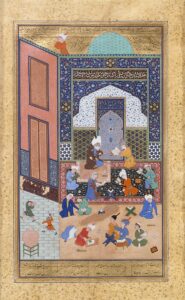

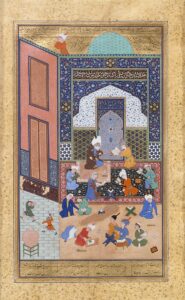

“Laila and Majnun in School”, Folio 129 from a Khamsa (Quintet) of Nizami of Ganja. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Moving further east, the tale of Layla and Majnun served as inspiration for artists. While the story originated in Arabic, it passed into Persian, Turkish, and Indian languages, denoting its popularity. In the 7th century, Bedouin Qays ibn al-Mulawwah fell in love with Layla bint Sa’d. These feelings were reciprocated, although the intensity of Qays’ obsessive passion expressed through poetry won him the epithet Majnun (meaning “possessed” or “mad”). Layla’s family, concerned about this outrageous public conduct, married her to another man. Upon hearing the news, Majnun exiled himself to the desert and adopted an ascetic lifestyle. Layla eventually became ill and died – some say of heartbreak. Majnun was later found dead in the wilderness near her grave, after carving three verses of poetry nearby proclaiming his undying love for Layla.

This tale has been told and re-told countless times because its themes of love and loss are universal. Majnun predated Dante by over half a millennium, but both poets were changed by their love, seeking to transcend physical bonds and attain a perfect, spiritual love. One of the most recognized versions of Layla and Majnun comes from a narrative poem composed in 1188 by Persian Nizavi Ganjavi. The story made it as far as Azerbaijan. There it became the Middle East’s first opera in 1908 thanks to renowned composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov. A scene from the poem was even depicted on the reverse of commemorative coins minted in 1996 for the 500th anniversary of Fuzûlî’s life, who originally adapted the story into Azerbaijani in the 16th century.

Layla and Majnun continue to fascinate people. In 2007-2008, Harvard University Art Museums hosted an exhibition on the representations of Majnun in Persian, Turkish, and Indian painting. Several manuscripts have been reproduced online, allowing viewers to immerse themselves more fully in the colorful world of these tragic lovers. The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Brooklyn Museum of Art have a series of Iranian wall paintings depicting the couple, as well as illuminated folios showing how they fell in love at first sight. The Cleveland Museum of Art also has a painting of the lovers meeting in the wilderness, as does the British Museum. Depictions of Layla and Majnun are so esteemed that modern fakes have been created to dupe potential buyers.

An authentic illustration at Harvard, “Illustrated Manuscript of Layla and Majnun,” has an interesting past. It is an illustrated copy of Hamdi’s version of Laila and Majnun, penned in 1499. This Turkish work was styled after the work of Jami, the famed Persian poet. The copy at Harvard is not dated, but notes on the manuscript indicate that it was copied in or around 1579, and that the copy may have been intended for the grand vizier at that time. However, subsequent owners are a mystery, and the work bears the square and oval seals of other owners. The manuscript contains 123 folios containing text and seven illustrations. The last folio likely contained a colophon (a printer’s mark), but unfortunately it is lost— the book continues a replacement folio. In addition, the lacquer binding on the book is also not original; it probably belonged to a Qajar manuscript of the late 18th century from Iran. Interesting, the inner sides of the book covers have been reversed to serve as outside covers.

The volume was eventually found its way to France. It likely was sold in Paris by Jean Soustiel in the 1970s to Edwin Binney, 3rd, and it was eventually bequeathed to Harvard University Art Museum in 1985.

Provenance: [Jean Soustiel, Paris, possibly May 1975], sold; to Edwin Binney, 3rd, by 1977, bequest; to Harvard University Art Museum, 1985.

We hope you have enjoyed this foray into works of art inspired by love and passion.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jan 19, 2022 |

Like other nations rich in archaeological material, Mexico has suffered a great deal of looting and illegal export of its cultural heritage over the past decades. Despite enacting protective legislation dating back to the late 19th century, cultural heritage objects from Mexico continue to be smuggled out of the country and sold on the open market. These items, many of which hail from pre-Columbian indigenous societies such as the Maya and Aztec, are highly prized by museums and private collectors alike. Stelae (free-standing commemorative monuments erected in front of pyramids or temples and made from limestone), polychrome vessels, jade and gold funerary masks, stone altars, and sculptured figurines are among the many types of objects offered for sale. This is a profitable business worldwide; according to Sotheby’s, its auctions of these items have reached nearly $45 million over the past 15 years. (One of our previous blog posts details the theft of pre-Columbian antiquities worth over $20 million from Mexico’s National Museum of Archaeology on Christmas Day 1985, and how authorities recovered them 3 years later.)

Pre-Colombian Stelea

Photo Credit: National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.

In light of these circumstances, Mexico has recently taken several concrete steps to strengthen efforts to track down and recover cultural and historical artifacts. In 2011, the National Institute for Anthropology and History (NIAH) announced the launch of a new unified database for cultural property, which allows for the inscription of cultural goods from anywhere within Mexico. Each item in the database is provided with a unique ID number and accompanying details (such as type, material, dimensions, and provenance), resulting in a publicly accessible and standardized system. This is an invaluable tool that will aid the government in protecting the country’s approximately 2 million movable artifacts.

Mexico has also implemented measures to further protect heritage items already removed from within its borders. In March 2013, the governments of Mexico, Guatemala, Costa Rica, and Peru contested the sale of pre-Columbian art from the Barbier-Mueller Museum at Sotheby’s Paris. All these countries have similar laws vesting ownership of antiquities in the State; therefore, they alleged that the sale was illegal because the objects were not accompanied by export licenses or sufficient provenance information confirming that the works were removed prior to the passage of the relevant laws. Nonetheless, the sale went ahead as planned. A French diplomat stated that the items did not appear on the Interpol database or ICOM Red List, and as such were not considered looted or stolen. (This statement was made even though pre-Columbian antiquities are underrepresented on both lists.) Ultimately, nearly half of the lots failed to sell, and the total sales proceeds fell far below the pre-sale estimate. Public pressure may have played a role in staving off bidders.

Despite this controversy, auctions of similar items have continued. In September 2019, Mexico and Guatemala jointly denounced the auction of pre-Columbian artifacts at French auction house Drouot. The auction house claimed the sale was “perfectly legitimate” and proceeded to sell 93% of the lots, netting $1.3 million for the sale. In response, the consigner, Alexandre Millon, stated that he was a victim of “opportunistic cultural nationalism.” This stoked further tension among countries of origin and market countries.

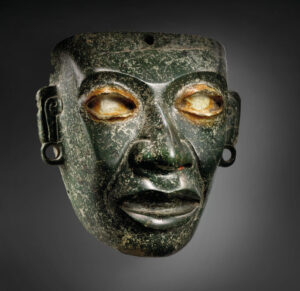

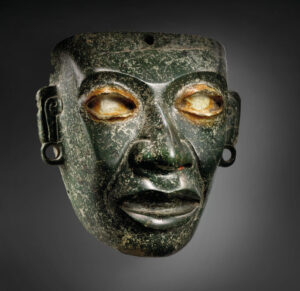

Teotihuacan mask, ca. 450–650

Photo Credit: Christie’s

In February 2021, NIAH lodged a formal legal claim against Christie’s over the sale of 33 pre-Columbian objects, including a stone sculpture of the goddess of fertility Cihuatéotl estimated at $722,000-$1.08 million and a Teotihuacán green stone mask of Quetzalcóatl estimated at $420,000-$662,000. Notably, the mask previously belonged to French dealer Pierre Matisse, son of artist Henri Matisse. While Christie’s maintained that it was confident in the legitimate provenance of the items, historian and archaeologist Daniel Salinas Córdova indicated that the circumstances under which the items had left their places of origin was still unclear. He reiterated that auctioning pre-Columbian antiquities is dangerous because it “promote[s] the commercialization and privatization of cultural heritage, prevent[s] the study, enjoyment, and dissemination of the artifacts, and promote[s] archaeological looting.” Although the sale proceeded and the legal claim has not yet been resolved, Mexico continues to enforce its patrimonial rights.

In September 2021, ambassadors from 8 Latin American Countries (Mexico, Bolivia, Costa Rica, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Panama, and Peru) banded together to stop an auction of pre-Columbian artifacts in Germany. Mexican Secretary of Culture Alejandra Faustro sent a letter to the Munich-based dealer, Gerhard Hirsch Nachfolger, citing Mexico’s 1934 patrimony law and reiterating the government’s commitment to recovering its cultural heritage. Mexico’s ambassador to Germany, Francisco Quiroga, even visited the auction house in person in an attempt to block the sale. A complaint was also filed with the Attorney General’s Office in Mexico. The auction took place, but of the 67 pieces identified as being Mexican, only 36 sold. Notably, one of the highlights – an Olmec mask with an estimate of €100,000 – did not achieve the reserve price.

That same month, Mexico announced the creation of a new team composed of National Guard personnel tasked with the recovery of stolen archaeological pieces and historical documents. The nation’s president, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, credited Italy with the idea. He stated, “Italy has a special body to recover stolen archaeological pieces. We are going to follow that example, I have given the instruction for the National Guard to constitute a special team for the purpose,” Lopez Obrador said.

As recently as November 2021, the Mexican government issued a letter questioning the legality of two auctions in Paris (at Artcurial and Christie’s) selling pre-Columbian objects. Embassy officials and the Mexican Secretary of Culture asked for the sales to be halted on the grounds that they “stri[p] these invaluable objects of their cultural, historical and symbolic essence, turning them into commodities or curiosities by separating them from the anthropological environment from which they come.” Only a few months earlier (in July), the governments of Mexico and France had signed a Declaration of Intent on the Strengthening of Cooperation against Illicit Trafficking in Cultural Property, which was meant to signal a recommitment towards the restitution and protection of each nation’s cultural heritage. Although Mexican officials appealed to UNESCO, bidding opened as scheduled on Artcurial’s online platform (with lots priced at $231-$11,600) and Christie’s earned over $3.5 million in its own sale. The day before the Christie’s sale, the embassies of Mexico, Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, and Peru in France issued a joint statement decrying the “commercialization of cultural property” and “the devastation of the history and identity of the peoples that the illicit trade of cultural property entails.”

Nonetheless, Mexico’s persistence has borne fruit. In September 2021, it was able to halt the sale of 17 artifacts at a Rome-based auction house. The Carabinieri TPC seized the objects after an inspection revealed that they had been illegally exported, and returned them to Mexico in October. The successful recovery of these objects demonstrates the importance of international cooperation. Many governments’ resources are stretched thin policing their own borders for cultural heritage smuggling and theft, and therefore greatly benefit from assistance by foreign law enforcement. It is also an example of how successful cultural diplomacy can be in the recovery of such objects.

The letter signed by Hernán Cortés recovered by the Mexican authorities.

Photo Credit: The National Archives

In addition to law enforcement and government agencies, laypeople have a crucial part to play in the recovery of looted or illegally exported artifacts. For instance, a group of academics in Mexico and Spain helped thwart the sale of a 500-year-old letter linked to conquistador Hernán Cortés. The letter, dating back to 1521, had been offered for sale by Swann Galleries in New York in September 2021. It was expected to fetch $20,000-$30,000. By searching online catalogues of global auction houses and a personal trove of photographs depicting Spanish colonial documents, the group traced the letter’s provenance to the National Archive of Mexico (NAM), a UNESCO World Heritage Site. An image of the letter had been taken by a Mormon genealogy project, which provided supporting evidence. Furthermore, the group unearthed 9 additional documents linked to Cortés that had been sold at auction – including at Bonhams and Christie’s – between 2017 and 2020. One of these had been sold previously at Swann Galleries for $32,500 and later displayed at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York as part of an exhibition. It was confirmed that all the documents had been stolen from the NAM – they were surgically excised from books – and illegally exported. In response, Swann Galleries cancelled the planned auction. The purchaser of the aforementioned letter returned it in good faith to the auction house. Mexico’s Foreign Ministry enlisted the help of the US Department of Justice to repatriate the 10 manuscripts, in cooperation with the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office and Homeland Security Investigations. The manuscripts were formally handed over in September 2021.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jan 5, 2022 |

After the Japanese military attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, the U.S. government began forcibly removing Japanese Americans from the West Coast and relocating them to isolated, inland areas. Around 120,000 people were detained in internment camps for the remainder of WWII. Among those interned were various artists – some were professional artists, some created works of art or crafts to occupy their time, and others used art to document their experiences during this uncertain time.

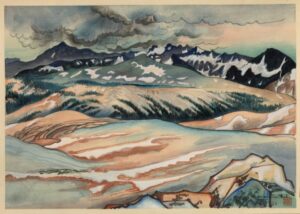

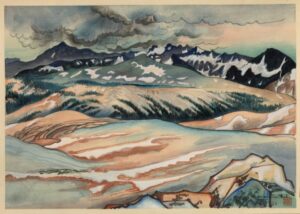

Chiura Obata, a notable artist and art teacher, was one such detained Japanese American artist. Last month, the Utah Museum of Fine Arts (UMFA) acquired thirty-five of Obata’s works created between 1934-1943, many of which were created during his internment in Utah.

Copyright: Archives of American Art, Chiura Obata Papers

Obata was a California-based artist who emigrated to the United States from Japan in 1903. After gaining notoriety early in his art career, Obata was named as a faculty member of the Art Department at the University of California, where he worked from 1932-1954. However, in the wake of the Pearl Harbor attacks, Obata and his family were relocated from their California home and interned. They were first sent to the Tanforan Detention Center (located in the Bay Area) and then to the Topaz War Relocation Center in Utah.

During his internment at each detention center, Obata served as a leader in creating art schools for detainees like himself. In addition to teaching, Obata created some 350 works during this period. These works included large-scale paintings of the landscapes surrounding the camps, drawings for the camp’s newspaper, and watercolors and sketches that documented life as a detainee (given that cameras were not permitted, artworks were used to create a record of daily life). Obata wished to show that he and his countrymen had not been defeated by the prejudice and humiliations they suffered.

Today, Obata is known for his brush and ink landscapes and portraits of America, in which he blends traditional Japanese brush styles with traditional Western techniques. Despite his time in the camps, Obata’s work shows a fascination with and focus on the rugged beauty of American landscapes, at odds with the ugliness of the detainment centers. He was able to find “the beauty that exists in enormous darkness.” The collection at the UMFA was donated by the Obata Estate. Representatives of the estate hope that “people will be inspired to learn the history of wartime incarceration and go visit the actual camp site in Delta as well as the Topaz Museum,” after viewing the pieces at the UMFA.

Chiura Obata, Great Nature, Storm on Mount Lyell from Johnson Peak, 1930, color woodcut on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Obata Family, 2000.76.8

Copyright: Lillian Yuri Kodani, 1989

In addition to this new collection, Obata has been featured in several exhibits and his works are in the permanent collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, the Smithsonian, and other well-known institutions.

Art created during this period of internment, however, went beyond Obata’s contributions. Many Japanese Americans had been artists previously or found solace in art during this period. George Matsusaburo Hibi was another notable artist interned with Obata. The two men worked together while at the Tanforan Assembly Center to create an art school, which eventually enrolled 600 students.

Before internment, Hibi was a student at the California School of Fine Arts. Throughout the 1930s, Hibi’s work was exhibited in the San Francisco area, and was even exhibited at the Oakland Art Gallery in 1943 while he was still interned in the camps. Hibi is primarily known for his printmaking and oil paintings. Many of his works depict the bleak aspects of the camp, including the harsh winters.

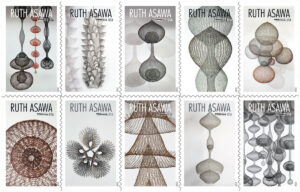

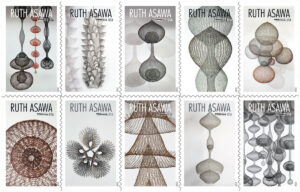

2020 Stamps honoring featuring Ruth Asawa’s art. Copyright: 2020 U.S. Postal Service.

Other notable interned artists were ones that worked as animators for Walt Disney Studios, including Tom Okamoto, Chris Ishii and James Tanaka. Like Hibi and Obata, these cartoonists also used their time at the internment camps to teach art. One of their students was Ruth Asawa, a young girl who had not previously explored art. While interned, however, she found free time to draw and explore her creative talents. Today, Asawa is a renowned artist with works in the Guggenheim Museum and the Whitney Museum in New York. She is known for her wire sculptures and the fountains she was commissioned to create in San Francisco. In 2020, the U.S. Postal Service honored her by featuring her art on a series of stamps.

During WWII, American Japanese internment camps were not the only camps that detained artists. In Nazi Germany, millions of people were forcibly interned. The circumstances and treatment of the prisoners at these camps varied, but in some cases, they were significantly crueler and more repressive. Unlike the U.S. internment camps, many Nazi camps were a mechanism to kill people. However, like the U.S. internment camps, they provided an unlikely source of inspiration and solace.

One famous artist who emerged from the camps was Kurt Schwitters. Schwitters had had gained renown as an artist for his involvement in the Dada movement, but in 1940 he was placed in a camp on the Isle of Man. Like the interned Japanese American artists on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, Schwitters created art in a studio and used his time to teach other prisoners, some of which became successful artists in their own right. However, creating and teaching art were not easy for Schwitters. Given the circumstances in the camps, art supplies were scarce. This forced Schwitters and other artists to become resourceful and find alternate tools to create art. People at the camp with Schwitters recall that he pulled up the linoleum flooring to paint on and even made a sculpture out of his porridge. Regardless of these obstacles, Schwitters produced over 200 works while at the camp. To honor these works and Schwitters’ legacy, a gallery near where he was interned exhibited his work. It attracted thousands of visitors in 2013.

Other works by imprisoned artists are honored at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum. The Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum is located at the site of the site of the former concentration camp and has a gallery with over 2,000 works of art that were created by prisoners at the various Nazi camps. In some of the more restrictive Nazi camps, art and any tools needed to create art were forbidden. Rather, works created in these camps were prepared in secret and using whatever supplies detainees could find. Many of the works were created to defy the Nazis and expose and document the atrocities occurring in the camps.

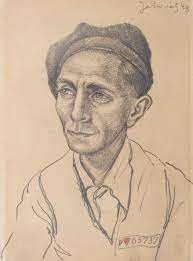

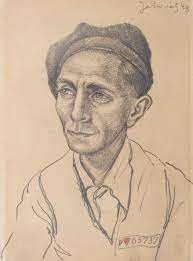

Drawing by Franciszek Jaźwiecki

Photo Credit: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum

Famously, Polish artist Franciszek Jaźwiecki secretly created a historical record through his portraits. An art historian at the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum believes that he drew these portraits for the purpose of creating a historical record, given that he included the prisoners’ numbers in each of his portraits. This has allowed historians to attach a name to the portraits through the number. Jaźwiecki took a huge risk by creating these drawings, as it was strictly prohibited. Records reveal that he hid his portraits in his bed or in his clothes. The portraits survived and after his death, his family donated 100 of his works to the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum in remembrance of his experience.

Many other such works and photographs have been uncovered. Historians believe that, like Jaźwiecki’s portraits, they were being used to document the people, conditions, and events in the camps. On display at the museum is a sketchbook with 22 pictures by an unknown artist. During his time at Auschwitz, he secretly drew the exterminations of detainees. His drawings were found in 1947 in a bottle that had been hidden in the foundations of a building near Birkenau’s crematoriums. This sketchbook is the only artwork uncovered that documents the extermination at Birkenau.

While internment camps are a difficult part of history, the art that was produced there reflects and documents this era. Art was both a practical tool for prisoners to occupy their time, but also contribute to newsletters and document the people and circumstances of the camps. It was additionally an emotional tool to help prisoners distract from their realities, retain their identity and purpose, and in many cases, to expose and cope with the bleak environments in which they were detained.