by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Mar 14, 2022 |

As practitioners working in the art and intellectual property realm, our team remains apprised of developments in these areas. Of course it is also a pleasure to publish articles on art and IP law topics for practitioners and others interested in these areas. Leila’s recent article for the Institute of Art & Law examines recent developments in copyright law. The landscape of copyright law has recently gone through unexpected developments with a number of cases that have left some artists uneasy about the Fair Use Exception and the use of copyrighted materials in appropriation art. Please contact the Institute of Art & Law for a copy of Leila’s informative article.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Mar 1, 2022 |

During conflict, art and heritage is often the target of aggression or simply collateral damage. As discussed in our post from last Friday, art and cultural heritage in Ukraine continues to be at risk during Russia’s invasion.

Sadly, the destruction of art has been confirmed. According to a tweet from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, one of the casualties from the attack on the Kyiv region was a collection of 25 paintings by notable Ukrainian artist, Maria Prymachenko. These works were stored in the Ivankiv Historical and Local History Museum which is located around 50 miles from Kyiv. While the destruction of the works has not been independently confirmed, several sources reported that the town in which the museum is located has been under fire. Further, satellite images show that the museum itself had been destroyed.

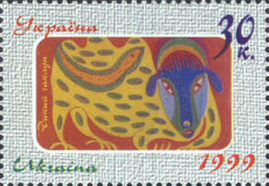

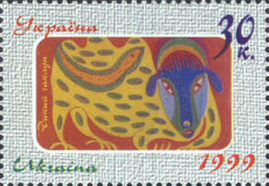

Ukrainian stamp featuring Maria Prymachenko’s art

Maria Prymachenko, who passed away in 1997 at the age of 88, was a self-taught artist best known for her colorful folk art. After seeing an exhibition of her work in Paris, Pablo Picasso stated, “I bow down before the artistic miracle of this brilliant Ukrainian.” The year 2009 was declared the Year of Maria Prymachenko by UNESCO. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ tweet highlighted Prymachenko for her “world-famous masterpieces” and “special gift and talent”. Her works have been honored by her home country, when they were featured on Ukrainian postage stamps. Ms. Prymachenko was also honored internationally, when UNESCO declared 2009 as the “Year of Maria Prymachenko.” Russia’s invasion has already caused significant destruction to several Ukrainian cities and one such casualty has been the museum and Prymachenko’s notable and priceless works.

Although not confirmed, social media reports that potentially looted Crimean artifacts have already appeared on the black market in the United Kingdom.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Feb 25, 2022 |

Armed conflict comes with multiple casualties, the most upsetting of which is the loss of human lives. However, the loss of cultural heritage is also significant. As history has shown on multiple occasions in recent years, notably in the case of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan in 2001, invading forces often destroy cultural heritage as a precursor of violence to come and as an intimidation tactic against local populations. Moreover, museums and other cultural institutions are subject to looting and theft during wartime. The Museum of Baghdad suffered such a fate in 2003, when it was ransacked for 36 hours, resulting in the loss of over 15,000 treasures. Thanks to recovery efforts spearheaded by law enforcement and U.S. forces, many of these objects have been tracked down and returned. But the situation remains precarious for Ukraine in the wake of Russia’s attack this week.

Motherland statue at the World War II Museum in Kyiv.

Photo Credits: REUTERS/Valentyn Ogirenko (taken by drone).

In the days leading up to Russia’s invasion, many art directors worried about the protection of Ukrainian museums and their collections. In particular, museum professionals expressed concerns over the potential destruction of arts institutions as air raids began, especially those in regions at high risk of attack. Institutions such as the Museum of Freedom, the National Art Museum of Ukraine, and The National Museum of the History of Ukraine in the Second World War are all located in Ukraine’s capital, Kyiv, which is vulnerable to attack and currently the site of clashes with the civilian population. Representatives of the National Museum of the History of Ukraine in the Second World War expressed concern not just about being a casualty of the incursion, but anticipated that the notable Motherland monument outside the building was a possible target. Museum directors also fear that items in their collections promoting democracy and critically portraying the 2014 Russian conflict may face targeted destruction by Russian troops.

Before reaching Kyiv, museums near Russian entry points into Ukraine, including Odessa and Kharkiv, were victims of military attacks. For instance, the Museum of the Kharkiv School of Photography was bombarded throughout the day on February 24. While most of its collection has been kept safe in Germany while the museum has been under renovations, remaining items are still vulnerable to damage, destruction, and theft.

Map of the reported fighting on February 24 in Ukraine, including Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Odessa.

Photo Credit: The New York Times

Many museums in the country have been left with limited options to protect their works. In anticipation of a possible invasion, Ukraine’s Ministry of Culture issued guidelines for the protection and evacuation of museum collections. However, there has not been much discussion of, or planning for, the protection of cultural heritage in the event of an invasion. Even when fully prepared, the evacuation of these collections is difficult. Packaging, crating, and shipping large collections is a costly endeavor that is not always included in museum budgets, particularly if public funds for the arts and culture sector have been depleted (such as COVID-19 recovery efforts). While some museums choose to send their most prized works abroad for protection, these works are still vulnerable to air attacks. Once Russian troops arrived in Ukraine on Thursday, on-the-ground evacuations were precluded because roads were blocked by fleeing civilians.

As a result, many museums were left to enact safety measures within the buildings themselves. Odessa Fine Arts Museum Director Aleksandra Kovalchuk stated that the museum staff was doing what it could to protect its collection of more than 10,000 objects. This included storing works in the basement and installing extra security measures, such as barbed wire barriers. Similarly, the National Museum of the History of Ukraine in the Second World War worked to move its most important works to a safe location.

Other museums, like the Museum of Freedom, started the process in advance of the conflict. Unfortunately, as a state museum, it needed prior approval from the government to physically remove any works from the premises. Museum Director Ihor Poshyvailo stated that the institution was forced to place important works in storage with museum staff members, who have taken turns guarding the collection. This may be a temporary measure, as Poshyvailo and other staff members could be recruited after President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine called on all able-bodied men under 60 in the country to fight.

Protestors in Odessa holding Ukrainian flag

Photo Credit: Oleksandr Gimanov/AFP via Getty Images

In addition to protecting the works in museum collections, some directors dedicated their efforts to raising international awareness about the risks to people, cities, and cultural heritage in Ukraine. The Director of the Mystetskyi Arsenal National Art and Culture Museum Complex in Kyiv, Olesia Ostrovska-Liuta, released an appeal for solidarity to the museum’s international partners. While Ostrovka-Liuta has since been evacuated to a bomb shelter, in her letter she called attention to the fact that “We should be preparing now the Book Arsenal to be held in May, exhibitions, and cross-sectoral projects — instead our team focuses the efforts to ensure the safety of our staff, our families, as well as to guard our collection, museum objects (paintings, graphics, fine art), including the artworks by Malevych, Yermylov, Bohomazov, Petrytskyi, Zaretskyi, etc., works of modern art, archaeological finds, and the Old Arsenal building, which is a historical and architectural monument of national importance.”

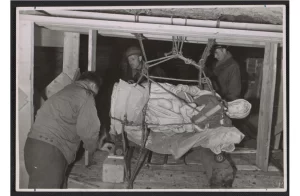

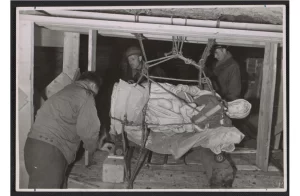

Ukraine’s struggles follow a long history of cultural heritage being damaged during conflict. Perhaps the best known and largest scale of looting and destruction took place during WWII. Countless items were forcibly taken from their owners and are still missing today, although there have been massive efforts to recover them since the end of the war. The Monuments Men were a group of 345 service members that significantly contributed to this effort. Between 1943 and 1951, the Monuments Men sought to track down and recover works that were stolen during the war. The service members of this group were able to recover over 5 million lost or stolen cultural objects.

Since WWII, many other countries have faced similar loss and destruction to their cultural heritage. Notably, the conflicts in Syria and Iraq over the past decades have left an insurmountable number of cultural heritage objects and sites destroyed, damaged, and looted. Today, scholars are still piecing together the extent of the cultural heritage that has been lost. Neither is Ukraine a stranger to this kind of destruction. During the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, Ukraine lost dozens of cultural and artistic collections. The Donetsk Regional Museum of Local HIstory was hit by anti-tank missiles a total of 15 times, destroying around 30% of their collection. Similarly, during the Maidan revolution, the National Art Museum of Ukraine was at the center of a battle between riot police and insurgents, leading to museum staff taking refuge in the building for many days in an effort to protect the works inside.

Monuments Men transporting a sculpture by Michelangelo, July 9, 1945. Photo credit: Thomas Carr Howe papers, Archives of American Art

Countries continue to fall victim to war, but measures have been established to safeguard art and culture. Primarily in response to the destruction and looting in war zones like parts of Syria and Iraq, there was an urgent need for such protective measures. In October 2019, the U.S. Army Reserve and the Smithsonian joined together to create a modern-day Monuments Men program, in honor of the WWII group. Together, these groups will train service members on how to respond to threats against and preserve cultural heritage. The destruction of cultural heritage has so often been collateral damage in these conflicts, but the creation of the modern Monuments Men program suggests a future in which preservation will be proactively considered and protected.

We hope that the conflict in Ukraine is resolved peacefully and that its people and rich cultural heritage are protected during this tumultuous period.