by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 27, 2022 |

Tiki statuette from the Marquesas Islands (currently in the Louvre)

Those who grew up watching The Brady Bunch re-runs on “Nick @ Nite” (or the popular series Scrubs) may recall a set of spooky episodes: the family’s ill-fated trip to Hawaii. What made the story arc so memorable was not the beautiful scenery, but that the narrative included a mysterious ancient curse. The curse comes into play when Bobby finds an ancient cultural artifact – a small tiki statue – and brings it home. Viewers quickly learn that whoever holds the statue experiences misfortune. The family ultimately returns the statue to a cave in order to break the curse, thus restoring peace and harmony to America’s favorite (1970s) TV family. As for Scrubs, main protagonists Turk and JD wear replicas of the tiki statue and face their own misfortunes, which they attribute to the curse.

These episodes are obviously fictional, but they illustrate an important aspect of cultural heritage; namely, how the provenance of an artwork or cultural artifact can influence modern perceptions and inspire stories that last for generations. In the case of the tiki statue, the modern misfortune attributed to the statue by the Bradys, Turk, and JD became part of its cultural identity.

Provenance

As we have highlighted in previous blog posts, provenance is an essential aspect of cultural heritage objects, as it reflects their history and cultural significance within a larger context. Not only does provenance delineate the proper origin and ownership of a piece, it also illuminates how contemporary culture influences the way an artifact is perceived in modern society. As part of our series of Halloween-themed posts, we are examining paintings, artifacts, and architectural sites whose provenance includes a spooky legend in modern culture. (You can also find last year’s “Unlucky Mummy” blog post here and the ghoulish frescoes of a Roman church here.

A Cursed Painting

The Rokeby Venus is Velázquez’s only surviving nude, and it is known to have a mysterious aura with a tendency to incite psychosis in its viewers. Diego Velázquez, a leading artist in King Phillip IV’s court in Spain, is the artist behind the hauntingly beautiful Rokeby Venus. More correctly referred to as The Toilet of Venus, the work goes by the name The Rokeby Venus in many modern descriptions after the English mansion (Rokeby Park) from where it was located from 1813-1906. The work depicts the goddess Venus gazing at a mirror being held by Cupid, who is shown as serving the goddess while she reclines. The hazy, unfocused gaze of the goddess makes it unclear whether Venus is using the mirror to view her own reflection or whether she is staring judgmentally at the viewer. This visual trick serves to both captivate and unnerve the audience, a dynamic that is particularly heightened by the historical origin of the work.

The Rokeby Venus is Velázquez’s only surviving nude, and it is known to have a mysterious aura with a tendency to incite psychosis in its viewers. Diego Velázquez, a leading artist in King Phillip IV’s court in Spain, is the artist behind the hauntingly beautiful Rokeby Venus. More correctly referred to as The Toilet of Venus, the work goes by the name The Rokeby Venus in many modern descriptions after the English mansion (Rokeby Park) from where it was located from 1813-1906. The work depicts the goddess Venus gazing at a mirror being held by Cupid, who is shown as serving the goddess while she reclines. The hazy, unfocused gaze of the goddess makes it unclear whether Venus is using the mirror to view her own reflection or whether she is staring judgmentally at the viewer. This visual trick serves to both captivate and unnerve the audience, a dynamic that is particularly heightened by the historical origin of the work.

Velázquez’s seductive portrayal of the goddess of love would have been a bold choice in light of the highly conservative mores of the Spanish court, heavily influenced by Catholicism. While modern viewers may find the piece less shocking than its original audience, the Rokeby Venus could be read as intentionally prurient, given Spanish politics at the time.

Psychosis

Venus’s overt sexuality and youthful beauty pinpoint the origins of the alleged curse. When the work was inherited by the 13th Duchess of Alba as part of her duchy, the renowned beauty hung the portrait on display in her quarters. But like the portrait of Dorian Gray brought to life by Oscar Wilde centuries later, the painting became a sinister reminder of the viewer’s mortality. According to rumor, the aging Duchess seems to have been unfamiliar with the concept of aging gracefully. Incensed by the unchanging youthfulness of Venus, while she, herself, battled the demons brought on by her deteriorating looks, the Duchess is believed to have committed suicide in response. Though there may have been other explanations for her tragic early death, her family and friends attributed the cause to none other than The Rokeby Venus.

When the work was next acquired by Don Manuel Godoy following the Duchess’s alleged suicide, the curse of The Rokeby Venus once again brought about its owner’s downfall. Prior to owning the painting, Godoy was – by all accounts – truly living his best life. As a respected and celebrated politician, he became extremely influential in the Spanish Royal Court. Then, Napoleon came into the picture. Suffice to say, it is difficult to blame the entire collapse of the Spanish imperial empire on a single individual. Even so, Spanish citizens gave it their best shot when they elected Godoy as their universal scapegoat. Godoy was eventually exiled from Spain and became a prisoner of Napoleon himself, later living a life of obscurity in Paris. His extreme reversal of fortune was blamed on the cursed Rokeby Venus.

After ruining Godoy’s life, The Rokeby Venus seemed content to withdraw for a while. During the next few changes of ownership, there were no reports of misfortune brought on by the painting. But then, in 1914, The Rokeby Venus curse reared its head. After being purchased by the National Gallery in London, the painting cast its malevolent spell on its next (and most recent) victim.

The slashed painting

Late on the night of March 10, 1914, English suffragette Mary Richardson broke into the National Gallery. She was armed with a meat cleaver and a single-minded goal: to destroy The Rokeby Venus. After slashing the painting seven times, she was apprehended by museum guards, who were perplexed: why attack this canvas? By way of motive, “Slasher Mary” (as she became known in the press) claimed that the Venus’ bare, rotund backside caused men to “gape at her” all day long, as if spellbound, when they visited the museum. She emphasized that the slashing was done in protest of the lascivious male gaze, and to support the advancement of women in their battle for political rights after the arrest of fellow suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst. In light of her statements, we are left to wonder whether Mary was really driven by political dogma, or whether she too was a victim of the madness said to be brought on by the painting’s display, which had lain dormant for a century. While the real answer is unknown, the spooky season invites us to imagine that Slasher Mary was driven to the brink by the painting’s alluring power.

An Unusual History

No matter what your opinion is of The Rokeby Venus’ alleged curse, the documented history of strange occurrences attributed to its ownership has become an important part of the work’s provenance. The stories behind The Rokeby Venus illustrate how all aspects of a work’s life – beginning with its origin and continuing through its interaction in a modern context – create a vivid tapestry of life behind what would otherwise be a merely decorative object. How a culture understands and makes sense of a piece gives the piece context, longevity, and life. For now, we continue to admire The Rokeby Venus, but let’s do so from afar.

The Rokeby Venus’s Provenance

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 19, 2022 |

Santo Stefano Rotondo, off the beaten path in Rome

In modern culture, horror movies set the standard for inciting fear in viewers. A pounding heartbeat, clammy palms, and the tendency to shriek aloud are all symptoms of a good old-fashioned Halloween horror film-fest. Incredibly, art can evoke the same – or even greater – psychological and mental responses in its viewers. This phenomenon is known as Stendhal Syndrome, named after a 19th century author who visited the Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence in 1817. Upon visiting the cultural site for the first time, he experienced an intense physical response to the artwork, writing, “I had palpitations of the heart, what in Berlin they call ‘nerves’. Life was drained from me. I walked with the fear of falling.” If Stendhal had been a woman, he may have swooned and required a swift dose of smelling salts to revive.

While Stendhal’s response was ultimately a positive one, Stendhal Syndrome has a dark side – it is known to provoke negative sensations in the viewer. The symptoms evoked by such artwork can range from physical responses, such as a quickened heartbeat or episodes of fainting, to mental disillusionment and even psychosis.

Gory frescoes covering the walls of the church

In fact, famed writer Charles Dickens found himself experiencing this overwhelming emotion when he visited Santo Stefano Rotondo in Rome. What Dickens encountered, which modern tourists can see as well, were gory frescoes depicting the macabre martyrdom of early Christian saints decorating the walls. These 16th century frescoes by Niccolo Circignani are not for the faint of heart: Roman martyrs are shown being flayed, boiled, vivisected, roasted, crucified and burned alive. When Dickens saw them for the first time, had he extreme discomfort. In his writings, he described the art as “a panorama of horror and butchery no man could imagine in his sleep,” likening his incredulity at the suffering as that of “poor old Duncan, in Lady MacBeth, when she marveled at his having so much blood in him.”

High praise indeed from a man who was known for his way with words. Dickens’ astonishment is matched by the reported reaction of another famous viewer, Pope Sixtus V. He visited the church shortly after the frescos’ initial debut. The Pope, it seems, burst into tears at the beauty represented by the faith of the butchered saints, and could not refrain from weeping.

One of the church’s bloody paintings

What makes these frescoes so memorable – and perhaps likely to cause nightmares for some viewers – is that they are impossibly distressing and even revolting. Not everyone has the stomach to face these depictions. While Circignani’s work speaks to a superior level of artistic mastery, it may be too intense for those uninitiated in the gory martyrdoms of the Catholic faith. Early Christian martyrs met their demise in shockingly disturbing ways, some so gruesome that they are almost unimaginable for modern sensibilities. At Santo Stefano Rotondo, Circignani has imagined these saints’ horrific ends for us, and painted them on the walls for all the world to see. For example, he displayed the torture of Saint Artemius, whose body was squashed between two slabs of stone. Circignani provided exquisite detail for an immersive experience in the saint’s painful final moments. He paints his eyes popping out of his sockets and fecal matter being expelled from his figure. Circignani further embraces the gore in his portrayal of Saint Agatha, whose breasts are in the process of being separated from her body with giant pincers. This Renaissance version of a haunted house – a house of body horrors – keeps intensifying with each depiction: a man on a butcher’s block being hacked apart with a machete, a forest full of amputated limbs dangling from tree branches, a saint carrying his own severed head, intestines bursting from abdomens, and more.

The purpose behind these macabre depictions of extreme torture and unfailing faithfulness in God in the face of persecution finds its origins in the battle between Catholics and Protestants to claim the true heirship of Christianity in the late 1500s. Catholics and Protestants during that time were no strangers to persecution, and the frescoes were meant to incite grit and perseverance in early Jesuit novices entering Santo Stefano, as well as in other faithful Catholics praying in the Church. In some ways, to the novices and other Catholics of the time, the frescoes served the same cultural purpose as athletes on Wheaties do today. The power of the image to evoke courage, heart, and perseverance in the face of difficulty is not new – but the subjects depicted and the artistic tactics used to emphasize such qualities in the viewer have certainly shifted.

The purpose behind these macabre depictions of extreme torture and unfailing faithfulness in God in the face of persecution finds its origins in the battle between Catholics and Protestants to claim the true heirship of Christianity in the late 1500s. Catholics and Protestants during that time were no strangers to persecution, and the frescoes were meant to incite grit and perseverance in early Jesuit novices entering Santo Stefano, as well as in other faithful Catholics praying in the Church. In some ways, to the novices and other Catholics of the time, the frescoes served the same cultural purpose as athletes on Wheaties do today. The power of the image to evoke courage, heart, and perseverance in the face of difficulty is not new – but the subjects depicted and the artistic tactics used to emphasize such qualities in the viewer have certainly shifted.

For the original patrons of Santo Stefano Rotondo in Rome, the goal of the frescoes was to shock viewers into a state of religious fervor. Now, they still serve to shock viewers, but may make them more nauseated than prepared to sacrifice life and limb for their faith in unbearably grotesque ways. The contrast between modern and historical reactions to the site emphasize how culture impacts a society’s acceptance – or rejection – of an artist’s work. Many modern viewers may instinctually turn away from the revolting nature of the frescos, when, in fact, Circignani’s intention was to draw the viewer in closer to the artwork as a path for a deeper relationship with God.

For the original patrons of Santo Stefano Rotondo in Rome, the goal of the frescoes was to shock viewers into a state of religious fervor. Now, they still serve to shock viewers, but may make them more nauseated than prepared to sacrifice life and limb for their faith in unbearably grotesque ways. The contrast between modern and historical reactions to the site emphasize how culture impacts a society’s acceptance – or rejection – of an artist’s work. Many modern viewers may instinctually turn away from the revolting nature of the frescos, when, in fact, Circignani’s intention was to draw the viewer in closer to the artwork as a path for a deeper relationship with God.

Santo Stefano Rotondo is a fantastic example of how the cultural perception of what is “art” and what is “disgusting” can change, depending on the cultural, societal, and political conditions at play for both the artist and the viewer. The full impact of the church is missed if one fails to recognize the full historical narrative of the site, in order to understand the depth of the cultural heritage on shockingly open display. If all else fails, one can at least appreciate Circignani’s macabre creativity in showing us the many shades of death and torture.

The rights in all the photos in this post belong to Leila A. Amineddoleh

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 4, 2022 |

The following guest blog post was written by Andrea Martín Alacid.

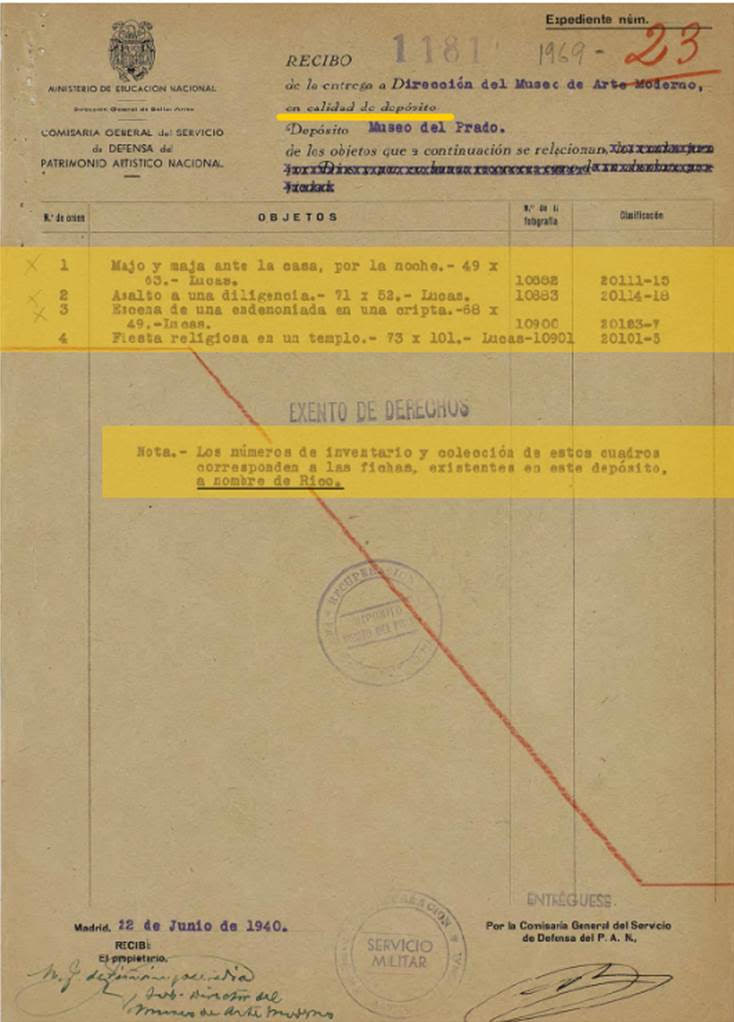

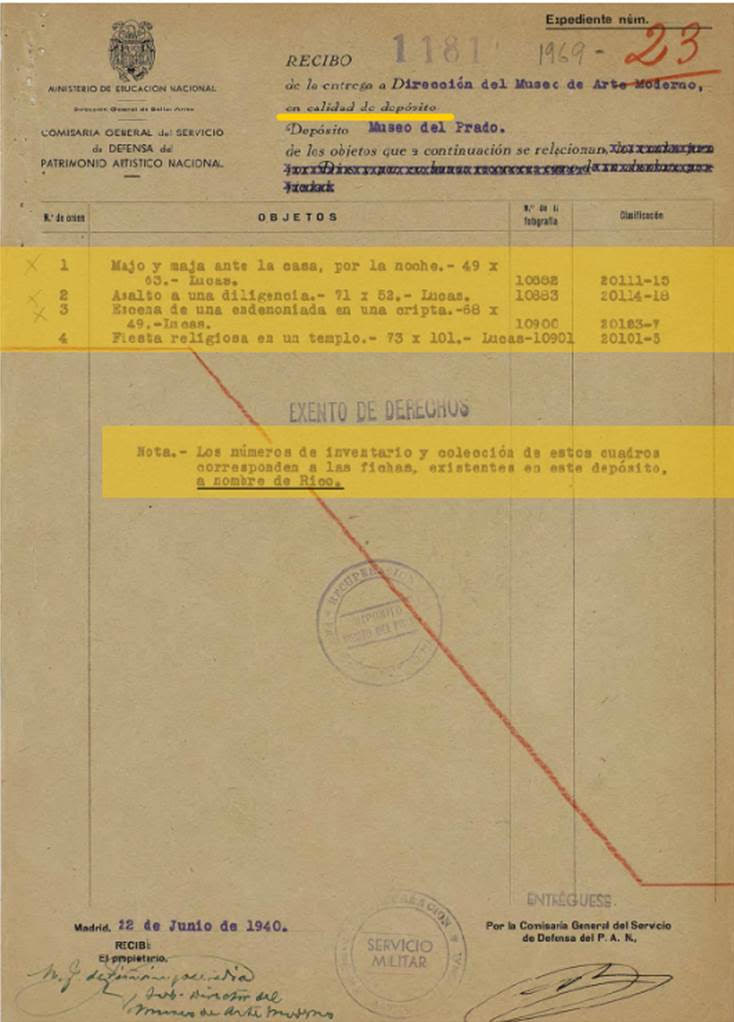

Following other European museums such as the Musée du Louvre in Paris and the British Museum in London, Museo Nacional del Prado (the Prado) in Madrid recently announced a new initiative. It would carry out an ex officio review of its collection to identify works of art seized during the Spanish Civil War and Franco’s regime by the Board of Seizure and Protection of Artistic Heritage founded in 1936 (and known as the Board of Artistic Treasure from 1937 onwards). Following the museum’s initiative, 25 documented works that were never returned to their rightful owners have been identified so far, but there is no doubt that this number could increase.

Following other European museums such as the Musée du Louvre in Paris and the British Museum in London, Museo Nacional del Prado (the Prado) in Madrid recently announced a new initiative. It would carry out an ex officio review of its collection to identify works of art seized during the Spanish Civil War and Franco’s regime by the Board of Seizure and Protection of Artistic Heritage founded in 1936 (and known as the Board of Artistic Treasure from 1937 onwards). Following the museum’s initiative, 25 documented works that were never returned to their rightful owners have been identified so far, but there is no doubt that this number could increase.

In response, the Prado has commissioned Professor Emeritus Arturo Colorado Castellary to lead a research project at the museum with the aim of clarifying the provenance of some of its works. His research will examine the background and context in which the works entered the Prado’s collections, in order to promote transparency and (if necessary and in compliance with all legal requirements) return them to their rightful owners. Professor Colorado is expected to share the first results of his research in early 2023.

Following the Prado’s announcement and after a great deal of research, this initiative has already borne fruit. The heirs of Pedro Rico López (a lawyer and Republican politician, as well as the mayor of Madrid in the 1930s), have begun the restitution process for the at least 25 paintings thus far. It was not until February 2021 that López’s grandchildren first learned about the whereabouts of their family’s artworks. The works were seized during the post-war period. The heirs eventually learned of the seized assets from an article, El botín del patrimonio español que el franquismo repartió en la posguerra (The spoils of Spanish heritage that Franco´s regime distributed in the post-war period), published in the Spanish national newspaper ABC, after Arturo Colorado’s research came to light . The heirs retained Spanish art law firm Caliope Art Law Boutique, founded by Laura Sánchez Gaona, to set forth their claim.

Following the Prado’s announcement and after a great deal of research, this initiative has already borne fruit. The heirs of Pedro Rico López (a lawyer and Republican politician, as well as the mayor of Madrid in the 1930s), have begun the restitution process for the at least 25 paintings thus far. It was not until February 2021 that López’s grandchildren first learned about the whereabouts of their family’s artworks. The works were seized during the post-war period. The heirs eventually learned of the seized assets from an article, El botín del patrimonio español que el franquismo repartió en la posguerra (The spoils of Spanish heritage that Franco´s regime distributed in the post-war period), published in the Spanish national newspaper ABC, after Arturo Colorado’s research came to light . The heirs retained Spanish art law firm Caliope Art Law Boutique, founded by Laura Sánchez Gaona, to set forth their claim.

As a result of the research carried out by the due diligence department of the law firm, along with the information provided by the Spanish General Directorate of Fine Arts, led by Isaac Sastre de Diego, the current location of 23 of the family’s artworks in various Spanish museums was discovered. In September 2021, members of the Caliope Art Law Boutique accompanied one of the heirs to identify the three Eugenio Lucas paintings in the custody of the Prado. The heirs had previously never seen these works in person. Although this was just a first step, it was an emotional moment for all those present, including Andrés Úbeda de los Cobos (Deputy Director of Conservation and Research) and Carlos Chaguaceda (Director of Communications) working on behalf of the Prado. While viewing the three paintings, it was noted that the Prado kept the Seizure Board’s labels intact. This is most valuable as the label recorded the name of the works’ rightful owner, Pedro Rico.

The paintings currently held by the Prado, together with the other works documented, have been in the possession of different administrations for a number of decades. Under the law of adverse possession in the Spanish Civil Code, the museums are considered the legal owners. However, the State Attorney General’s Office has recently reevaluated this doctrine in the context of plundered works of art. As a result, the first restitution of a work of art seized during the Civil War took place last month. The recipients are the family of Ramón de la Sota Chalbaud, and the work in question is Portrait of a Young Gentleman by Cornelis can der Voort. This landmark restitution has paved the way for new cases to come.

The paintings currently held by the Prado, together with the other works documented, have been in the possession of different administrations for a number of decades. Under the law of adverse possession in the Spanish Civil Code, the museums are considered the legal owners. However, the State Attorney General’s Office has recently reevaluated this doctrine in the context of plundered works of art. As a result, the first restitution of a work of art seized during the Civil War took place last month. The recipients are the family of Ramón de la Sota Chalbaud, and the work in question is Portrait of a Young Gentleman by Cornelis can der Voort. This landmark restitution has paved the way for new cases to come.

In short, there is no doubt that this initiative by the Prado, together with the re-evaluation of adverse possession, is a crucial and significant step in the restitution procedures of looted cultural heritage in Spain, which unfortunately lack a specific legal framework at this time. It is likely that this framework will be developed in the near future, and we eagerly await ongoing developments.

We congratulate our esteemed colleagues and friends in Spain for their remarkable work fighting for justice and paving the way for equitable restitutions in Europe.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Sep 27, 2022 |

As everyone in the fashion industry knows, September means one thing: fashion week. With New York Fashion Week already behind us, Milan Fashion Week coming to a close, and Paris Fashion Week mere days from kicking off, the intersection of art, high fashion, and daily life has come together in multiple shows celebrating streetwear as haute couture (although this isn’t the first time fashion brands have taken visual inspiration from art on the street).

As everyone in the fashion industry knows, September means one thing: fashion week. With New York Fashion Week already behind us, Milan Fashion Week coming to a close, and Paris Fashion Week mere days from kicking off, the intersection of art, high fashion, and daily life has come together in multiple shows celebrating streetwear as haute couture (although this isn’t the first time fashion brands have taken visual inspiration from art on the street).

Looking rumpled, it turns out, is an art form. Custom, high-end designer streetwear is no new phenomenon. Take fashion designer Dapper Dan’s (Daniel Day’s) styling of hip-hop moguls in the 1980s. Through innovative silk-screening and layering techniques (and at a hefty price-point), Dapper Dan fused high fashion with an everyday wearability, heightening the drama of the growing hip-hop music scene. For Dapper Dan (who goes by “Dap”) and others who take guidance from his work, including Savile Row’s Rav Matharu of Clothsurgeon’s bespoke streetwear, the challenge of creating these garments lies in blending high-end luxury with the lifestyle the current wearer is already living. This sometimes involves the use of someone else’s corporate branding in the streetwear’s design. As a result, promoting and selling the final product can become nearly as tricky as the production of the garment itself.

Dapper Dan, for example, famously faced legal challenges from Italian fashion giants Gucci and Fendi, for screen-printing their logos on his leather pieces and outwear designs. In fact, Dapper Dan faced so many lawsuits from Fendi, Gucci, and other luxury brands after incorporating their logos into his designs that he was sued out of business in 1992 and forced to close his Harlem boutique.

The reason fashion houses are often quick to initiate lawsuits when they see their work being used elsewhere is because fashion is a billion-dollar global industry. Yes, artistic ingenuity, originality, and fame are at stake when a designer’s work or logo is being copied without authorization – but so is the potential for a large settlement.

Often, the exact amount that is paid in a settlement is kept private between the parties to the lawsuit, such as the case between Hell’s Angels and luxury designer Alexander McQueen. In 2010, Hell’s Angels sued McQueen for using its “winged skull” motif on bags and jewelry. Not only did McQueen settle with Hell’s Angels for an undisclosed amount, but the suit became so intense that the fashion house actually promised to destroy the merchandise that contained the Hell’s Angels winged skull design.

The secrecy element begs the question: how much is an undisclosed settlement worth in a fashion trademark lawsuit? Gucci’s lawsuit against fast-fashion brand Guess may provide some insights. In 2012, Guess paid Gucci $4.7 million dollars in damages for trademark infringement of Gucci’s interlocking “G” and diamond print logo that Guess used on shoes and other accessories. However, this settlement, astonishing as it was, was considered a blow to Gucci, because it was only a portion of what Gucci had requested in litigation (a staggering $221 million dollars). Gucci’s expectations in this case serve to illustrate both the motivation and the mindset of big fashion houses in their dogged pursuit of trademark claims.

While protecting artistic originality is certainly one of the benefits of fashion trademark lawsuits, along with preventing consumer confusion, there is a strong argument against initiating trademark-based lawsuits involving streetwear brands, specifically. This is because streetwear style can be traced to the intersectionality and collaboration behind the 1970s hip-hop movement. The community-building expression of the diasporic cultural narratives of Black, Latinx, and Caribbean histories continue to provide a foundation for the styles seen on this fall’s runways. The roots of streetwear, both on stage and in the audience, are principled on the sharing, refining, and reworking of culture. Thus, streetwear must reference (and sometimes infringe upon) our worship of consumeristic branding, in order to use those same brands to tell a new story.

Due to this process, Dapper Dan (“Dap”) is a good example of a streetwear designer whose artistic freedom thrives on appropriating other designers as a form of cultural commentary. In the words of rapper Darold Ferguson, Jr (“A$AP Ferg”), [w]hat Dap did was take what those major fashion labels were doing and made them better.” In doing so, “Dap curated hip-hop culture.” Through this lens of Dap as a “cultural curator,” Dap’s forced closure of his boutique in 1992 becomes even more heartbreaking, because it was the result of legal challenges brought against him by large fashion houses with significantly greater financial resources. This worked against his emergence as both an outstanding artistic talent and a cultural icon.

A framework for streetwear designers to cohabitate with luxury brands in the industry in a way that is artistically and economically beneficial to both sides is clearly required. Fortunately, for Dap, this came to fruition in the re-emergence of his Harlem boutique in 2018, reincarnated through his son’s opening of a new Harlem store. The joint venture was backed by none other than Gucci – the same Gucci whose legal challenges once threatened to ruin Dap.

Dap and Gucci’s collaboration provides a basis for streetwear designers to obtain artistic freedom to reinvent styles through commentary on current culture, the results of which construct a stage to effect social change. At the same time, streetwear brands are not forced to appropriate luxury trademarks to spark activism through fashion. Avoiding trademark infringement in streetwear is a tall order, but it can be done. At this year’s fashion week, it was done flawlessly.

Take Disco Inferno & 14N1’s Fall 2022 show entitled More Fashion, Less Gun Violence, to witness a stunning evocation of streetwear fashion’s ability to tell the story of humankind. The show brings hope to an incredibly dark shared history, and does so through an impeccable (if casual) fit.

When checking out the shows this year, keep an eye out for the intersection of streetwear and high-fashion, and how the combination references the roots of the American hip-hop cultural movement. Notice the dominance of luxury logos featured on runway models and front-row attendees, alike. Should brands be prevented from reworking luxury trademarks in their designs in order to criticize contemporary culture? When should the law protect the fashion houses, and their economic stakes, by protecting their marks?

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Sep 15, 2022 |

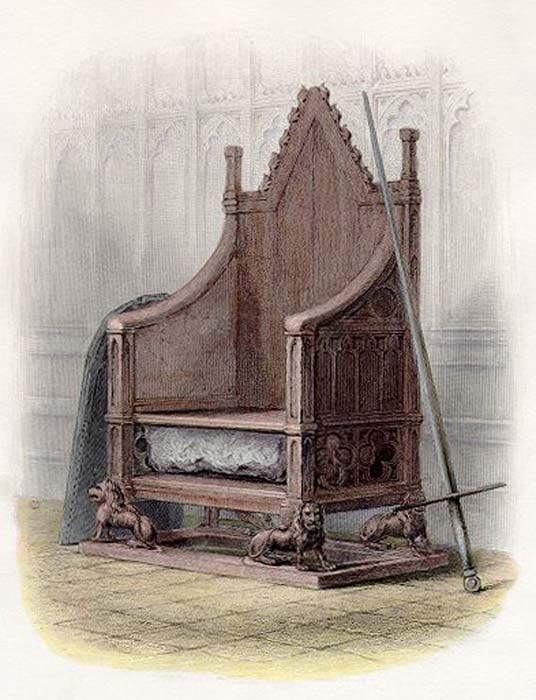

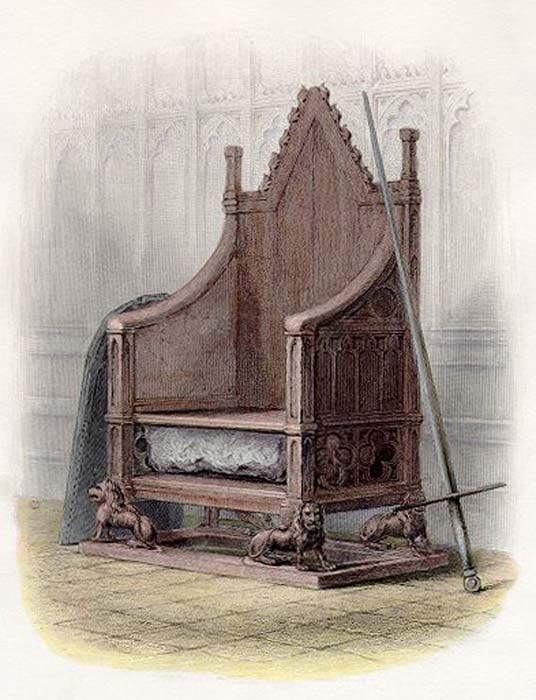

The Stone of Scone in Westminster Abbey

Last week’s passing of the cultural and political icon, Queen Elizabeth II, marks the end of an era, as well as the beginning of a new reign for her son, King Charles III. While the King’s coronation is a long way off (likely to take place in 2023), preparations for the events are already underway. Centuries-old traditions are being planned to punctuate the big day, including the assemblage of one of the globe’s most exclusive guest lists. And the most important guest on that list is an enormous slab of rock. Not to be confused with The Rock, the Stone of Scone is an ancient Scottish artifact. And it is what it sounds like – a large, grey stone – and its presence at the coronation is nearly as essential as His Majesty’s.

Edward Longshanks (portrayed in Braveheart). Copyright: 20th Century Fox Film Corp

Originally used as a throne by the ancient Scots to crown their rulers, the Stone was stolen by King Edward I during the Scottish Wars of Independence in the late 13th century. In stealing the Stone, King Edward sought to send a message to the Scots by establishing himself as their rightful monarch. Unbeknownst to Edward, the Scottish people did not intend for such pillaging to go unpunished, even if the retaliation did not take place until centuries in the future.

In 1950, four unlikely heroes – a motley group of students, led by ringleader Ian Hamilton – snatched the Stone from its place in the Chapel in Westminster Abbey. The quartet then literally carted the antiquity back to Scotland in not one – but two (more on that below) – Ford Anglias. The heist – though ultimately successful – did not occur without a hitch (hence, the two Fords). During the dislodging of the Stone from King Edward’s Chair in King Edward’s tomb, the Stone somehow slipped and smashed to the floor, breaking into two pieces. Not to be deterred, the foursome quickly bundled up the Stone in two packages. One piece was placed in Ford #1, which set off for home. The second piece was tucked into the trunk of Ford #2, driven by our ringleader, Hamilton.

Unfortunately for Hamilton, the night’s struggles were not quite complete, and as dawn broke over the horizon, a policeman approached the car, curious as to why two students were quickly and nervously dashing away from the Abbey at 5am. Hamilton and his fellow passenger jumped into a feigned lover’s embrace, and, after swapping a few innuendos with the policeman, were sent happily on their way.

This resolved the exit part of the theft, yet left unresolved the issue with the Stone being smashed into two pieces. Upon arrival in Scotland, the Stone received some TLC and a professional mending by a stonemason, who, in addition to doing fantastic masonry, was also phenomenal at keeping secrets. The mason fixed the Stone and breathed not a word to the authorities. But several months later, police received a call about the whereabouts of the Stone: it had been deposited in the Arbroath Abbey in Scotland. This is where the Stone remained until 1952, when it was returned to Westminster Abbey in England.

This resolved the exit part of the theft, yet left unresolved the issue with the Stone being smashed into two pieces. Upon arrival in Scotland, the Stone received some TLC and a professional mending by a stonemason, who, in addition to doing fantastic masonry, was also phenomenal at keeping secrets. The mason fixed the Stone and breathed not a word to the authorities. But several months later, police received a call about the whereabouts of the Stone: it had been deposited in the Arbroath Abbey in Scotland. This is where the Stone remained until 1952, when it was returned to Westminster Abbey in England.

And what about our “bravehearted” student thieves? They were eventually questioned by the authorities, leading Hamilton to confess the entire episode. However, none of the students faced prosecution for their theft, due to the incredible political implications of the heist and the ensuing renewed vigor for Scottish nationalism and devolution efforts.

The 1950 theft became both infamous and synonymous with a separate and distinct Scottish identity, as essentially a testament in itself to the history of independent Scottish reign. In fact, the theft became so closely associated with Scottish independence that England’s return of the Stone to Scotland in 1996 is believed to have been a catalyst for the vote for Scottish devolution in 1997.

Today, the Stone remains in Scotland and travels to England only for the coronation of a new British monarch. As the Stone comes back into the global zeitgeist due to the preparations for England’s crowning of a new King, the Stone’s cultural, political, and historical significance cannot be overlooked. The Stone – and its rare journey between the two Abbeys – encompasses the history of the Scottish monarchy, the legitimacy of British rule, the enduring spirit of Scottish cultural identity, and the undercurrent of thievery and war.

Our thoughts are with the Royal Family and all citizens of the United Kingdom during this time of mourning.

The Rokeby Venus is Velázquez’s only surviving nude, and it is known to have a mysterious aura with a tendency to incite psychosis in its viewers. Diego Velázquez, a leading artist in King Phillip IV’s court in Spain, is the artist behind the hauntingly beautiful Rokeby Venus. More correctly referred to as The Toilet of Venus, the work goes by the name The Rokeby Venus in many modern descriptions after the English mansion (Rokeby Park) from where it was located from 1813-1906. The work depicts the goddess Venus gazing at a mirror being held by Cupid, who is shown as serving the goddess while she reclines. The hazy, unfocused gaze of the goddess makes it unclear whether Venus is using the mirror to view her own reflection or whether she is staring judgmentally at the viewer. This visual trick serves to both captivate and unnerve the audience, a dynamic that is particularly heightened by the historical origin of the work.

The Rokeby Venus is Velázquez’s only surviving nude, and it is known to have a mysterious aura with a tendency to incite psychosis in its viewers. Diego Velázquez, a leading artist in King Phillip IV’s court in Spain, is the artist behind the hauntingly beautiful Rokeby Venus. More correctly referred to as The Toilet of Venus, the work goes by the name The Rokeby Venus in many modern descriptions after the English mansion (Rokeby Park) from where it was located from 1813-1906. The work depicts the goddess Venus gazing at a mirror being held by Cupid, who is shown as serving the goddess while she reclines. The hazy, unfocused gaze of the goddess makes it unclear whether Venus is using the mirror to view her own reflection or whether she is staring judgmentally at the viewer. This visual trick serves to both captivate and unnerve the audience, a dynamic that is particularly heightened by the historical origin of the work.

The purpose behind these macabre depictions of extreme torture and unfailing faithfulness in God in the face of persecution finds its origins in the battle between Catholics and Protestants to claim the true heirship of Christianity in the late 1500s. Catholics and Protestants during that time were

The purpose behind these macabre depictions of extreme torture and unfailing faithfulness in God in the face of persecution finds its origins in the battle between Catholics and Protestants to claim the true heirship of Christianity in the late 1500s. Catholics and Protestants during that time were  For the original patrons of Santo Stefano Rotondo in Rome, the goal of the frescoes was to shock viewers into a state of religious fervor. Now, they still serve to shock viewers, but may make them more nauseated than prepared to sacrifice life and limb for their faith in unbearably grotesque ways. The contrast between modern and historical reactions to the site emphasize how culture impacts a society’s acceptance – or rejection – of an artist’s work. Many modern viewers may instinctually turn away from the revolting nature of the frescos, when, in fact, Circignani’s intention was to draw the viewer in closer to the artwork as a path for a deeper relationship with God.

For the original patrons of Santo Stefano Rotondo in Rome, the goal of the frescoes was to shock viewers into a state of religious fervor. Now, they still serve to shock viewers, but may make them more nauseated than prepared to sacrifice life and limb for their faith in unbearably grotesque ways. The contrast between modern and historical reactions to the site emphasize how culture impacts a society’s acceptance – or rejection – of an artist’s work. Many modern viewers may instinctually turn away from the revolting nature of the frescos, when, in fact, Circignani’s intention was to draw the viewer in closer to the artwork as a path for a deeper relationship with God.

Following other European museums such as the Musée du Louvre in Paris and the British Museum in London, Museo Nacional del Prado (the Prado) in Madrid recently announced a new initiative. It would carry out an ex officio review of its collection to identify works of art seized during the Spanish Civil War and Franco’s regime by the Board of Seizure and Protection of Artistic Heritage founded in 1936 (and known as the Board of Artistic Treasure from 1937 onwards). Following the museum’s initiative, 25 documented works that were never returned to their rightful owners have been identified so far, but there is no doubt that this number could increase.

Following other European museums such as the Musée du Louvre in Paris and the British Museum in London, Museo Nacional del Prado (the Prado) in Madrid recently announced a new initiative. It would carry out an ex officio review of its collection to identify works of art seized during the Spanish Civil War and Franco’s regime by the Board of Seizure and Protection of Artistic Heritage founded in 1936 (and known as the Board of Artistic Treasure from 1937 onwards). Following the museum’s initiative, 25 documented works that were never returned to their rightful owners have been identified so far, but there is no doubt that this number could increase. Following the Prado’s announcement and after a great deal of research, this initiative has already borne fruit. The heirs of Pedro Rico López (a lawyer and Republican politician, as well as the mayor of Madrid in the 1930s), have begun the restitution process for the at least 25 paintings thus far. It was not until February 2021 that López’s grandchildren first learned about the whereabouts of their family’s artworks. The works were seized during the post-war period. The heirs eventually learned of the seized assets from an article, El botín del patrimonio español que el franquismo repartió en la posguerra (The spoils of Spanish heritage that Franco´s regime distributed in the post-war period), published in the Spanish national newspaper ABC, after Arturo Colorado’s research came to light . The heirs retained Spanish art law firm

Following the Prado’s announcement and after a great deal of research, this initiative has already borne fruit. The heirs of Pedro Rico López (a lawyer and Republican politician, as well as the mayor of Madrid in the 1930s), have begun the restitution process for the at least 25 paintings thus far. It was not until February 2021 that López’s grandchildren first learned about the whereabouts of their family’s artworks. The works were seized during the post-war period. The heirs eventually learned of the seized assets from an article, El botín del patrimonio español que el franquismo repartió en la posguerra (The spoils of Spanish heritage that Franco´s regime distributed in the post-war period), published in the Spanish national newspaper ABC, after Arturo Colorado’s research came to light . The heirs retained Spanish art law firm  The paintings currently held by the Prado, together with the other works documented, have been in the possession of different administrations for a number of decades. Under the law of adverse possession in the Spanish Civil Code, the museums are considered the legal owners. However, the State Attorney General’s Office has recently reevaluated this doctrine in the context of plundered works of art. As a result, the first restitution of a work of art seized during the Civil War took place last month. The recipients are the family of Ramón de la Sota Chalbaud, and the work in question is Portrait of a Young Gentleman by Cornelis can der Voort. This landmark restitution has paved the way for new cases to come.

The paintings currently held by the Prado, together with the other works documented, have been in the possession of different administrations for a number of decades. Under the law of adverse possession in the Spanish Civil Code, the museums are considered the legal owners. However, the State Attorney General’s Office has recently reevaluated this doctrine in the context of plundered works of art. As a result, the first restitution of a work of art seized during the Civil War took place last month. The recipients are the family of Ramón de la Sota Chalbaud, and the work in question is Portrait of a Young Gentleman by Cornelis can der Voort. This landmark restitution has paved the way for new cases to come. As everyone in the fashion industry knows, September means one thing:

As everyone in the fashion industry knows, September means one thing:

This resolved the exit part of the theft, yet left unresolved the issue with the Stone being smashed into two pieces. Upon arrival in Scotland, the Stone received some TLC and a professional mending by a stonemason, who, in addition to doing fantastic masonry, was also phenomenal at keeping secrets. The mason fixed the Stone and breathed not a word to the authorities. But several months later, police received a call about the whereabouts of the Stone: it had been deposited in the

This resolved the exit part of the theft, yet left unresolved the issue with the Stone being smashed into two pieces. Upon arrival in Scotland, the Stone received some TLC and a professional mending by a stonemason, who, in addition to doing fantastic masonry, was also phenomenal at keeping secrets. The mason fixed the Stone and breathed not a word to the authorities. But several months later, police received a call about the whereabouts of the Stone: it had been deposited in the