Finding of the Sybilline Books and the Tomb of Numa Pompilius, ca. 1524–1525, workshop of Giulio Romano with Polidoro Caldara da Caravaggio. Bibliotheca Hertziana. Courtesy of the Getty Museum.

Like with fine art, it is important to look at the provenance of antiquities. But understanding the history of antiquities involves more than just provenance (the ownership history). It is also essential to examine the provenience (the work’s findspot). A work’s provenience includes more than where it was excavated, it describes the context in which the item was found, providing scholars with essential information about its origin, use, and importance. For instance, the same object might be understood differently if it is found at an altar than if it were found relegated to a corner. Because objects moved across ancient trade routes, their findspots are important to our understanding about exchanges between cultures. Unfortunately, when looters strip an archaeological site of its valuables, scholars lose this context and we are denied access to important knowledge. Plunder and illegal export of antiquities from around the world pose the threat of irreparable harm to mankind’s cultural heritage.

Provenience is also instrumental in resolving ownership disputes, particularly in the application of national patrimony laws. In order for a nation to demand the return of an object originating from within its borders under the National Stolen Property Act, that country must have enacted a patrimony law that vests ownership of the property to the nation. If artifacts are excavated and removed in contravention to these laws, they become stolen goods. As in all matters of theft, the party demanding the return of property (here the nation), must establish rightful ownership. This can be a very challenging task in the case of looted antiquities as a nation might not become aware of a looted item’s existence for many years, and because looted objects typically are not accompanied by paperwork attesting to their pasts.

Very often, antiquities have huge gaps in provenance because these works remain underground–both literally and figuratively–for centuries. An item kept in a tomb for centuries is never exhibited nor passed from owner to owner, and so does not develop a provenance that helps to provide clear title to the artwork. In such cases, the modern provenance (the post-excavation record) of certain antiquities may be appealing to collectors. Generally, the longer a work has been in the public eye, the lower chance a nation might claim it was looted or exported illegally.

The Vatican Museums boast one of the most impressive art and antiquities collection in the world. For the past five centuries, Laocoön and His Sons has been one of its gems, depicting nearly life-size figures from the Trojan War. Laocoön, a priest of Apollo in the city of Troy, warned his fellow Trojans against taking in the wooden horse left by the Greeks outside the city gates. Athena and Poseidon, who favored the Greeks, sent two great sea-serpents to kill Laocoön and his two sons. From the Roman point of view, the death of these innocents was crucial to the decision of Aeneas, who heeded Laocoön’s warning, to flee Troy, leading to the eventual founding of Rome.[1]

The Vatican Museums boast one of the most impressive art and antiquities collection in the world. For the past five centuries, Laocoön and His Sons has been one of its gems, depicting nearly life-size figures from the Trojan War. Laocoön, a priest of Apollo in the city of Troy, warned his fellow Trojans against taking in the wooden horse left by the Greeks outside the city gates. Athena and Poseidon, who favored the Greeks, sent two great sea-serpents to kill Laocoön and his two sons. From the Roman point of view, the death of these innocents was crucial to the decision of Aeneas, who heeded Laocoön’s warning, to flee Troy, leading to the eventual founding of Rome.[1]

Scholars categorize the work as being of the Hellenistic “Pergamene baroque,” a style that began in Greek Asia minor in the 3rd century BC (the best known work being the Pergamon Altar (circa 180-160 BC). In Hellenistic fashion, Laocoön and His Sons displays attention to the accurate depiction of movement: the three men desperately try to break free from the hold of the sinuous serpents. No matter how much they struggle, they remain tragically entangled.

Most historians believe that the marble sculpture is a copy of an earlier bronze. Due to its style and subject matter, art historians believe the original Laocoön and His Sons was sculpted around 200 BCE in Pergamon. This theory is supported by Pliny the Elder who admires the piece in Volume XXXVI of Natural History. He attributes the work to three sculptors from Rhodes, and places its location in the palace of the Emperor Titus, where it possibly remained until its modern discovery.

The statue group was found on the Esquiline Hill in Rome and immediately identified as the Laocoön as described by Pliny the Elder. The group was excavated in February 1506 in the vineyard of Felice De Fredis. At the request of Pope Julius II, Michelangelo and Giuliano da Sangallo were present at the unearthing. Sangallo’s son, only 11-years-old at the time, wrote an account about the excavation over sixty years later:

The statue group was found on the Esquiline Hill in Rome and immediately identified as the Laocoön as described by Pliny the Elder. The group was excavated in February 1506 in the vineyard of Felice De Fredis. At the request of Pope Julius II, Michelangelo and Giuliano da Sangallo were present at the unearthing. Sangallo’s son, only 11-years-old at the time, wrote an account about the excavation over sixty years later:

“The first time I was in Rome when I was very young, the Pope [Julius II] was told about the discovery of some very beautiful statues in a vineyard near Santa Maria Maggiore [on the Esquiline Hill]. The pope ordered one of his officers to run and tell Giuliano da Sangallo to go and see them. He set off immediately. Since Michelangelo Buonarroti was always to be found at our house, my father having summoned him and having assigned him the commission of the Pope’s tomb, my father wanted him to come along too. I joined up with my father and off we went. I had climbed down to where the statues were, when immediately my father said, ‘That is the Laocoon, which Pliny mentions.’ Then they dug the hole wider so that that they could pull the statue out. As soon as it was visible everyone started to draw, all the while discoursing on ancient things, chatting about the ones [ancient statues owned by the Medici] in Florence.”[2]

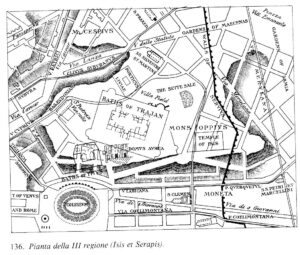

The exact spot of its finding was not clear for centuries, except for vague statements, such as “near Santa Maria Maggiore” or “near the site of the Domus Aurea.” The vineyard of Felice de Fredis, noted in the sales document to the Pope, was just inside the Servian Wall on the southern spur of the Esquiline, east of the Sette Sale (the cisterns) supplying the nearby imperial Baths of Titus and Trajan which were built over the reviled Domus Aurea of Nero. This area was once the site of the Gardens of Maecenas, where Tiberius later resided.[3] This information was ascertained from a document recording De Fredis’ purchase of the vineyard 14 months before the statue’s discovery. (De Fredis’ house survives today.)

Pope Julius II immediately acquired the group and had it displayed in the Cortile delle Statue (Courtyard of the Statutes), making it the centerpiece of the collection. A base was eventually added in 1511. The Laocoön’s discovery influenced art into the Baroque period, with Michelangelo particularly taken by the piece. The sculptural group was depicted in prints and small models, becoming famous throughout Europe. The work is widely regarded as one of mankind’s greatest artistic achievements. Countless writers have mused about its qualities, with Johann Joachim Winkelmann writing about the paradox of admiring beautiful in a depiction of death and failure. Johann Goethe wrote of the work, “A true work of art, like a work of nature, never ceases to open boundlessly before the mind. We examine, — we are impressed with it, — it produces its effect; but it can never be all comprehended, still less can its essence, its value, be expressed in words.[4]

The statue faced an uncertain future toward the end of the 18th century. In July 1798 it was taken to France in the wake of the French conquest of Italy. It was displayed when the new Musée Central des Arts, later the Musée Napoléon, opened at the Louvre in November 1800. After Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo, when much of the art plundered by France was returned, the Laocoön returned to the Vatican in January 1816.

Few pieces in existence today can match the superb provenience of Laocoön and His Sons, typically leaving antiquities collectors with limited knowledge when making a purchase. In truth, some collectors have developed a tolerance for scant information, accepting that some degree of risk will always be present in the market. In such cases, collectors rely on the information that is available, namely the work’s provenance since it reemerged into the public’s awareness. One exemplary piece with a rich provenance is a 900-year-old large black stone carving of Lokanatha from India sold through Christie’s Auction House in 2017.

Leiko Coyle with the record-breaking antiquity. Courtesy of Christie’s.

Standing nearly five feet tall and carved from a single piece of stone, the work depicts a seated Lokanatha Avalokiteshvara, the Buddhist deity embodying compassion. Lokanatha is identified by a seated Buddha set in the center of his crown and a long, blooming lotus draped over his left shoulder. The piece also features plump, youthful feet typical of portrayals of divinity and interlocking coils of hair (not unlike the serpents entangling Laocoön and his sons). Although the statue has lost both arms, a common occurrence for Buddhist statues that have survived to modernity, Lokanatha retains a striking and illuminating presence.

The work’s power is due in part to its impressive size, a trait that sets it apart from other works made during the same era. The piece is dated to the Pala Period of the 12th century, which was named for the expansive empire that then controlled what is now West Bengal in India and Bangladesh. This empire produced remarkably detailed and sophisticated works of sculpture, making pieces such as the Lokanatha highly sought after by collectors.

The physical characteristics are not the only thing that attracted bidders to this piece: it has a sterling provenance. “The most remarkable thing about this sculpture, besides its quality and sheer size, is its provenance,” says Christie’s specialist Leiko Coyle in the weeks leading up to auction.[5] Ms. Coyle worked with the consignor to successfully investigate the provenance of the exquisite piece. The work first reappeared in 1922 as the centerpiece of one of America’s first collections of Indian art, established by the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The work then entered a private European collection in 1976, where it remained for 40 years before going up for sale.

The catalog entry for the piece recounts the following information:

“It was first acquired in the year 1922 for the Boston Museum by none other than Dr. Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy (1877-1947)… In 1917, when the museum was already world famous for its rich collection of Chinese and Japanese art, it obtained a substantial assemblage of Indian art from Coomaraswamy who had begun amassing the material mostly in India under the British Raj around 1910. At the time there was no restriction in the movement of art among the various nations or from continent to continent. One of the greatest patrons and benefactors of the museum Dr. Denman Ross (1853-1935), a wealthy Bostonian and a professor of art and design at Harvard University (as well as a MFA trustee) had been steadily forming a vast private collection of art of global diversity, including India since the late 19th century... Ross and Coomaraswamy had met in London in the first decade of the 20th century and it was largely due to their cooperation that the museum had secured the famous Goloubew Collection of Indian and Persian paintings in 1914 which Coomaraswamy would publish a few years after joining the museum in 1917.”

The work’s history and public display assured buyers with a level of confidence that the statue would likely not be subject to a repatriation claim. In a market with imperfect records, this is an ideal history.In the case of the Lokanatha, that confidence translated to a sale price of $24.6 million dollars, setting a record for South Asian art.

[1] http://www.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani/en/collezioni/musei/museo-pio-clementino/Cortile-Ottagono/laocoonte.html

[2] Letter of Francesco da Sangallo, quoted in Leonard Barkan, Unearthing the Past: Archaeology and Aestheticsin the Making of Renaissance Culture (1999)

[3] https://www.ancientworldmagazine.com/articles/laocoon-suffering-trojan-priest-afterlife/

[4] Upon the Laocoon

[5] 5 minutes with… A 900-year-old Indian Pala-period statue, Christie’s (Mar. 16, 2017), https://www.christies.com/features/Leiko-Coyle-with-a-South-East-Asian-Pala-figure-8088-1.aspx.