by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 27, 2022 |

Tiki statuette from the Marquesas Islands (currently in the Louvre)

Those who grew up watching The Brady Bunch re-runs on “Nick @ Nite” (or the popular series Scrubs) may recall a set of spooky episodes: the family’s ill-fated trip to Hawaii. What made the story arc so memorable was not the beautiful scenery, but that the narrative included a mysterious ancient curse. The curse comes into play when Bobby finds an ancient cultural artifact – a small tiki statue – and brings it home. Viewers quickly learn that whoever holds the statue experiences misfortune. The family ultimately returns the statue to a cave in order to break the curse, thus restoring peace and harmony to America’s favorite (1970s) TV family. As for Scrubs, main protagonists Turk and JD wear replicas of the tiki statue and face their own misfortunes, which they attribute to the curse.

These episodes are obviously fictional, but they illustrate an important aspect of cultural heritage; namely, how the provenance of an artwork or cultural artifact can influence modern perceptions and inspire stories that last for generations. In the case of the tiki statue, the modern misfortune attributed to the statue by the Bradys, Turk, and JD became part of its cultural identity.

Provenance

As we have highlighted in previous blog posts, provenance is an essential aspect of cultural heritage objects, as it reflects their history and cultural significance within a larger context. Not only does provenance delineate the proper origin and ownership of a piece, it also illuminates how contemporary culture influences the way an artifact is perceived in modern society. As part of our series of Halloween-themed posts, we are examining paintings, artifacts, and architectural sites whose provenance includes a spooky legend in modern culture. (You can also find last year’s “Unlucky Mummy” blog post here and the ghoulish frescoes of a Roman church here.

A Cursed Painting

The Rokeby Venus is Velázquez’s only surviving nude, and it is known to have a mysterious aura with a tendency to incite psychosis in its viewers. Diego Velázquez, a leading artist in King Phillip IV’s court in Spain, is the artist behind the hauntingly beautiful Rokeby Venus. More correctly referred to as The Toilet of Venus, the work goes by the name The Rokeby Venus in many modern descriptions after the English mansion (Rokeby Park) from where it was located from 1813-1906. The work depicts the goddess Venus gazing at a mirror being held by Cupid, who is shown as serving the goddess while she reclines. The hazy, unfocused gaze of the goddess makes it unclear whether Venus is using the mirror to view her own reflection or whether she is staring judgmentally at the viewer. This visual trick serves to both captivate and unnerve the audience, a dynamic that is particularly heightened by the historical origin of the work.

The Rokeby Venus is Velázquez’s only surviving nude, and it is known to have a mysterious aura with a tendency to incite psychosis in its viewers. Diego Velázquez, a leading artist in King Phillip IV’s court in Spain, is the artist behind the hauntingly beautiful Rokeby Venus. More correctly referred to as The Toilet of Venus, the work goes by the name The Rokeby Venus in many modern descriptions after the English mansion (Rokeby Park) from where it was located from 1813-1906. The work depicts the goddess Venus gazing at a mirror being held by Cupid, who is shown as serving the goddess while she reclines. The hazy, unfocused gaze of the goddess makes it unclear whether Venus is using the mirror to view her own reflection or whether she is staring judgmentally at the viewer. This visual trick serves to both captivate and unnerve the audience, a dynamic that is particularly heightened by the historical origin of the work.

Velázquez’s seductive portrayal of the goddess of love would have been a bold choice in light of the highly conservative mores of the Spanish court, heavily influenced by Catholicism. While modern viewers may find the piece less shocking than its original audience, the Rokeby Venus could be read as intentionally prurient, given Spanish politics at the time.

Psychosis

Venus’s overt sexuality and youthful beauty pinpoint the origins of the alleged curse. When the work was inherited by the 13th Duchess of Alba as part of her duchy, the renowned beauty hung the portrait on display in her quarters. But like the portrait of Dorian Gray brought to life by Oscar Wilde centuries later, the painting became a sinister reminder of the viewer’s mortality. According to rumor, the aging Duchess seems to have been unfamiliar with the concept of aging gracefully. Incensed by the unchanging youthfulness of Venus, while she, herself, battled the demons brought on by her deteriorating looks, the Duchess is believed to have committed suicide in response. Though there may have been other explanations for her tragic early death, her family and friends attributed the cause to none other than The Rokeby Venus.

When the work was next acquired by Don Manuel Godoy following the Duchess’s alleged suicide, the curse of The Rokeby Venus once again brought about its owner’s downfall. Prior to owning the painting, Godoy was – by all accounts – truly living his best life. As a respected and celebrated politician, he became extremely influential in the Spanish Royal Court. Then, Napoleon came into the picture. Suffice to say, it is difficult to blame the entire collapse of the Spanish imperial empire on a single individual. Even so, Spanish citizens gave it their best shot when they elected Godoy as their universal scapegoat. Godoy was eventually exiled from Spain and became a prisoner of Napoleon himself, later living a life of obscurity in Paris. His extreme reversal of fortune was blamed on the cursed Rokeby Venus.

After ruining Godoy’s life, The Rokeby Venus seemed content to withdraw for a while. During the next few changes of ownership, there were no reports of misfortune brought on by the painting. But then, in 1914, The Rokeby Venus curse reared its head. After being purchased by the National Gallery in London, the painting cast its malevolent spell on its next (and most recent) victim.

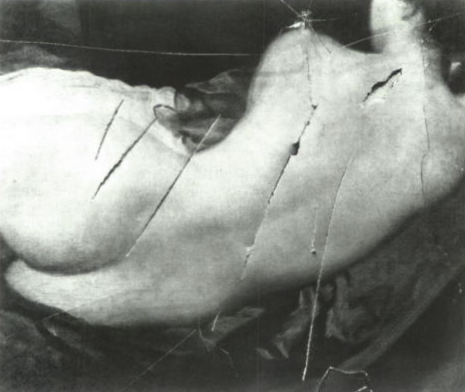

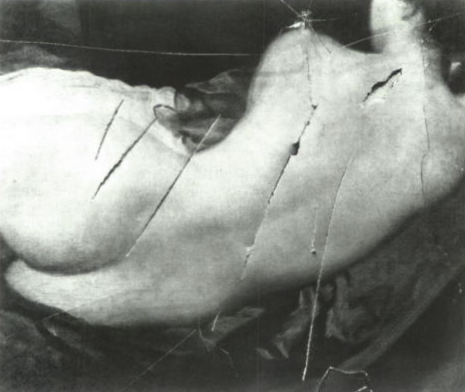

The slashed painting

Late on the night of March 10, 1914, English suffragette Mary Richardson broke into the National Gallery. She was armed with a meat cleaver and a single-minded goal: to destroy The Rokeby Venus. After slashing the painting seven times, she was apprehended by museum guards, who were perplexed: why attack this canvas? By way of motive, “Slasher Mary” (as she became known in the press) claimed that the Venus’ bare, rotund backside caused men to “gape at her” all day long, as if spellbound, when they visited the museum. She emphasized that the slashing was done in protest of the lascivious male gaze, and to support the advancement of women in their battle for political rights after the arrest of fellow suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst. In light of her statements, we are left to wonder whether Mary was really driven by political dogma, or whether she too was a victim of the madness said to be brought on by the painting’s display, which had lain dormant for a century. While the real answer is unknown, the spooky season invites us to imagine that Slasher Mary was driven to the brink by the painting’s alluring power.

An Unusual History

No matter what your opinion is of The Rokeby Venus’ alleged curse, the documented history of strange occurrences attributed to its ownership has become an important part of the work’s provenance. The stories behind The Rokeby Venus illustrate how all aspects of a work’s life – beginning with its origin and continuing through its interaction in a modern context – create a vivid tapestry of life behind what would otherwise be a merely decorative object. How a culture understands and makes sense of a piece gives the piece context, longevity, and life. For now, we continue to admire The Rokeby Venus, but let’s do so from afar.

The Rokeby Venus’s Provenance

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Feb 13, 2022 |

In honor of Valentine’s Day, the latest blog post in our Provenance Series centers on the stories of famous lovers and the art inspired by them.

Most people are familiar with playwright William Shakespeare’s famed star-crossed lovers, Romeo and Juliet. This pair from Verona has been immortalized in music, films, subsequent works of literature, and countless works of art. However, there are other ill-fated romantic couples that deserve to share the artistic spotlight.

Dante and Betrice by Henry Holiday

Dante Alighieri, widely credited as the father of modern Italian language, wrote his magnum opus in the 13th century after falling in love with a woman known as Beatrice. Dante admired her from a distance, having only met with Beatrice twice, the first time when they were both nine years old. These interactions moved him so profoundly that Beatrice is widely credited as Dante’s muse even though she was married to another man. Beatrice first appears in Dante’s autobiographical text La Vita Nuova, where she is portrayed as a courtly lady. Beatrice died in 1290. Dante then composed a three-volume narrative poem describing the author’s journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise, where he is eventually reunited with his lady love. This work, The Divine Comedy, is considered one of the great masterpieces of world literature and it was deeply inspired by Dante’s feelings for Beatrice. Indeed, Beatrice serves as the epitome of grace and beauty. She guides the pilgrim Dante into heaven, where his worldly love is transformed into divine love.

Paolo and Francesca da Rimini by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

While Dante and Beatrice meet a happy end in the spiritual realm, other couples in The Divine Comedy are not so fortunate. Paolo Malatesta and Francesca da Rimini were real-life contemporaries of Dante who make an appearance in Canto V of the Inferno. Francesca was the wife of Paolo’s brother, who killed them both in a rage after he discovered their secret union. As adulterous lovers, the pair is bonded together for eternity in a fiery whirlwind, symbolizing their uncontrollable lust. But it seems that Dante empathized with Paolo and Francesca’s plight; he wrote that they fell in love while reading medieval romances, particularly those depicting Lancelot and Guinevere (another doomed duo). Upon hearing this, Dante is overcome with pity and weeps for their fate. Despite only occupying 69 lines in Dante’s epic poem, this depiction influenced subsequent generations of artists, particularly the Romantics in the 19th century.

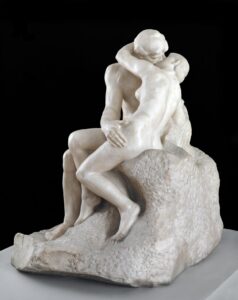

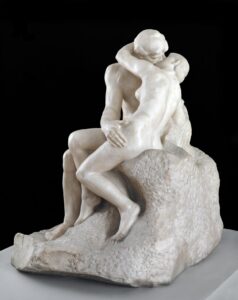

The Kiss, by Auguste Rodin

The poet’s own idealized yet bittersweet love was a favorite subject of the Pre-Raphaelite painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti, whose father was a Dantean scholar and who was in fact named after the Florentine poet. Rossetti used Elizabeth “Lizzie” Siddal and Jane Morris as models for Beatrice. In a case of life imitating art, Rossetti’s relationships with Siddal and Morris both ended unhappily. Rossetti painted Beata Beatrix after Siddal’s tragic death from an overdose of laudanum in 1862. The painting has various renditions, all placing the titular Beatrice (with Siddal’s characteristic red hair) in a beam of light, symbolizing her spiritual transfiguration. Later, Auguste Rodin’s famous 1880s sculpture “The Kiss” was originally titled “Francesca da Rimini.” The original pose was reportedly so passionate that it was censored at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair due to fears that it would incite “lewd behavior.” Rodin was eventually persuaded to change the monumental marble’s name. Yet Paolo and Francesca still appear in the bronze work “The Gates of Hell,” directly inspired by Dante’s Inferno.

Even 700 years after his death, Dante’s work remains highly prized. In 2017, three “tome-raiders” stole over £2 million worth of antiquarian books (over 160 items) from a London warehouse. The stolen property included a rare 1569 edition of The Divine Comedy. The thieves managed to evade the security system by entering the warehouse from above. They bored holes into the reinforced glass skylights and lowered themselves 40 feet on ropes, similar to the film Mission Impossible. The criminals likely received inside information on the location of the valuable books, leading to the heist. The international rare book market is worth approximately $500 million a year. Unfortunately, that means that thieves target valuable manuscripts for the illicit trade. Unfortunately, book theft has been on the rise. However, because of the notoriety of the stolen works, here the thieves’ options were to issue a ransom demand or attempt to sell the goods on the black market for a fraction of the price (5-10%). Fortunately, the books were recovered in Romania in 2020 before they were offered for sale. The crime was linked to various organized crime families with “a history of complex and large-scale high value thefts.”

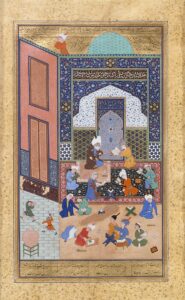

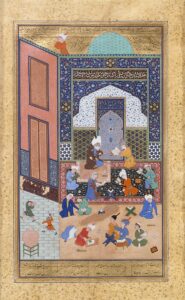

“Laila and Majnun in School”, Folio 129 from a Khamsa (Quintet) of Nizami of Ganja. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Moving further east, the tale of Layla and Majnun served as inspiration for artists. While the story originated in Arabic, it passed into Persian, Turkish, and Indian languages, denoting its popularity. In the 7th century, Bedouin Qays ibn al-Mulawwah fell in love with Layla bint Sa’d. These feelings were reciprocated, although the intensity of Qays’ obsessive passion expressed through poetry won him the epithet Majnun (meaning “possessed” or “mad”). Layla’s family, concerned about this outrageous public conduct, married her to another man. Upon hearing the news, Majnun exiled himself to the desert and adopted an ascetic lifestyle. Layla eventually became ill and died – some say of heartbreak. Majnun was later found dead in the wilderness near her grave, after carving three verses of poetry nearby proclaiming his undying love for Layla.

This tale has been told and re-told countless times because its themes of love and loss are universal. Majnun predated Dante by over half a millennium, but both poets were changed by their love, seeking to transcend physical bonds and attain a perfect, spiritual love. One of the most recognized versions of Layla and Majnun comes from a narrative poem composed in 1188 by Persian Nizavi Ganjavi. The story made it as far as Azerbaijan. There it became the Middle East’s first opera in 1908 thanks to renowned composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov. A scene from the poem was even depicted on the reverse of commemorative coins minted in 1996 for the 500th anniversary of Fuzûlî’s life, who originally adapted the story into Azerbaijani in the 16th century.

Layla and Majnun continue to fascinate people. In 2007-2008, Harvard University Art Museums hosted an exhibition on the representations of Majnun in Persian, Turkish, and Indian painting. Several manuscripts have been reproduced online, allowing viewers to immerse themselves more fully in the colorful world of these tragic lovers. The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Brooklyn Museum of Art have a series of Iranian wall paintings depicting the couple, as well as illuminated folios showing how they fell in love at first sight. The Cleveland Museum of Art also has a painting of the lovers meeting in the wilderness, as does the British Museum. Depictions of Layla and Majnun are so esteemed that modern fakes have been created to dupe potential buyers.

An authentic illustration at Harvard, “Illustrated Manuscript of Layla and Majnun,” has an interesting past. It is an illustrated copy of Hamdi’s version of Laila and Majnun, penned in 1499. This Turkish work was styled after the work of Jami, the famed Persian poet. The copy at Harvard is not dated, but notes on the manuscript indicate that it was copied in or around 1579, and that the copy may have been intended for the grand vizier at that time. However, subsequent owners are a mystery, and the work bears the square and oval seals of other owners. The manuscript contains 123 folios containing text and seven illustrations. The last folio likely contained a colophon (a printer’s mark), but unfortunately it is lost— the book continues a replacement folio. In addition, the lacquer binding on the book is also not original; it probably belonged to a Qajar manuscript of the late 18th century from Iran. Interesting, the inner sides of the book covers have been reversed to serve as outside covers.

The volume was eventually found its way to France. It likely was sold in Paris by Jean Soustiel in the 1970s to Edwin Binney, 3rd, and it was eventually bequeathed to Harvard University Art Museum in 1985.

Provenance: [Jean Soustiel, Paris, possibly May 1975], sold; to Edwin Binney, 3rd, by 1977, bequest; to Harvard University Art Museum, 1985.

We hope you have enjoyed this foray into works of art inspired by love and passion.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Nov 9, 2021 |

This entry in our ongoing Provenance Series addresses the phenomenon of unexpected archaeological discoveries and their role in spurring historical and cultural research.

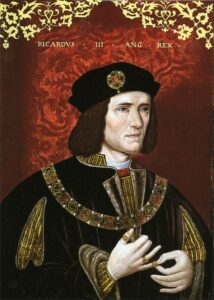

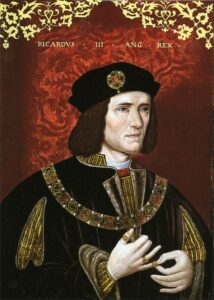

Portrait of Richard III in the National Portrait Gallery

Archeologists often spend years digging for and uncovering cultural heritage artifacts around the world. These artifacts serve as windows into the past and are pivotal in piecing together the history of the world and its myriad cultures. Some famous discoveries, however, were found entirely by accident rather than by careful planning. For example, in 1974, a group of Chinese farmers digging a well struck the head of a clay figure with their shovels. The resulting excavation revealed an ancient tomb with thousands of life-size sculptures depicting horses and warriors in full armor and battle formation, guarding the remains of an emperor. We now know of the sculptures as the Terra Cotta Warriors. In 1947, a Bedouin goat and sheep herder searching for his lost goat happened upon a cave that contained papyrus scrolls later confirmed to be the Dead Sea Scrolls. These contain some of the earliest known writings from the Bible and new fragments are still being discovered today.

While some discoveries were unexpected because they were found by accident, other discoveries are shocking due to the location where they were found. The body of Richard III, a king from the Plantagenet line who ruled England during the medieval Wars of the Roses (and later inspired one of Shakespeare’s plays), was famously uncovered in a parking lot in Leicester in 2012, after a group of archeologists from the local university and members of the Richard III Society coordinated efforts to find his body. Previously, it was believed that Richard III had been buried in Greyfriars Church in Leicester, which was likely destroyed during the reign of Henry VIII.

Over the past few years, there have been several notable unexpected discoveries, including the following:

4,000-year-old Log Coffin in a Pond at an English Golf Course

A 4,000-year-old log coffin containing human remains and a “perfectly preserved ax” was discovered in a small pond at the Tetney Golf Club near Grimsby, England. The club owner’s feared that the discovery would hurt business, and the excavation team sought to obtain sufficient information about the artifacts. Hence, although the discovery was made in the summer of 2018, it was not announced until this past September.

Three years ago, workers on the golf course were using a large excavator to carry out improvements to the pond. Unexpectedly, it collided with a very large, hard object. The owners of the course notified local authorities and luckily Hugh Willmott, an archeologist and senior lecturer at the University of Sheffield, and his archeological team were working at a nearby excavation site. They were able to arrive at the golf course the next day to carry out rescue measures.

Over the past three years archeologists, historians, and conservationists have been completing preservation works on these fragile artifacts. The coffin is around three meters long and one meter wide and is believed to be from the Bronze Age (since log coffins are only known to have been used then). The man in the coffin was estimated to be tall for that time (5 foot 9 inches), approximately in his 30s or 40s at the time of death, and likely someone of great stature in his community. The axe is considered rare, as only 12 of this type have been discovered in Britain. It has a wooden handle and a stone head, and is believed a “symbol of authority” rather than a tool used in practice.

Given the size of the coffin, the conservation process is still under way. Once complete, the coffin and axe will be displayed at the Collection Museum, an art and archeological museum in Lincolnshire. The discovery has been called a “brilliant learning experience” and is expected to produce valuable information on ancient regional burial practices.

Roman Artifacts Discovered Under an Abandoned Medieval Church near London

A CGI image showing what St. Mary’s Church may have looked like when built. Image: courtesy of HS2

Less than 150 miles from the golf course, another major find was discovered. Earlier this month, a team unearthed three Roman statues and a rare glass jug as they concluded their dig at St. Mary’s Church in Stoke Mandeville, a town 46 miles outside of London.

The “once in a lifetime” and “uniquely remarkable” find included two full stone torsos and heads of an adult man and woman, and a stone head of what appears to be a child. The lead archeologist noted the exceptional preservation of the sculptures, commenting: “[Y]ou really get an impression of the people they depict—literally looking into the faces of the past is a unique experience.” In addition, the team also uncovered pieces of a very rare and surprisingly intact hexagonal glass jug, for which there is only one other comparable item; the other job was discovered in Tunisia and is now on display at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The artifacts were discovered at the site of an ancient Norman church. Researchers believe this site might originally have been a Bronze Age burial site. It was then the site of a Roman mausoleum built during the Roman occupation of Britain. Finally, it served as the site of St. Mary’s church, which was erected around 1080 C.E, renovated in the 13th 14th, and 17th centuries, and eventually torn down in the mid-20th century. This site’s rich history has been at the center of other archeological discoveries, including 3,000 bodies at the burial site of the church, Roman cremation urns, and painted walls and roof tiles.

This dig, funded by the U.K.’s national Department of Transport, is one of 60 sites that will be excavated ahead of the construction of the new H2S high-speed railway. This new, controversial railway will connect the expanse of the United Kingdom, but some surveys suggest that there are nearly 1,000 potential excavation sites along the proposed 350-mile route. It remains to be seen whether other archaeological discoveries will come to light.

Subway Station Development in Rome Leads to Additional Discoveries

In Rome, archeologists have been excavating at Amba Aradam in preparation for a new subway station that will connect Rome’s city center to towns in the eastern perimeter of the metropolitan area. Because the subway line is being built over 100 feet below ground, this has allowed archeologists to excavate much deeper than usual and, as a result, make a number of significant discoveries.

A Roman domus (not the one found under the subway station)

In 2016, the dig uncovered a military barrack from the 2nd C.E., during the rule of Emperor Hadrian. The find was so impressive that the government plans to create the city’s first “archaeological station.” Two years later, the team found a domus, or house, with a central courtyard, frescoed walls, patterned mosaic floors, a fountain, at least 14 rooms, rare wooden artifacts, and a similar sized structure 40 feet below ground, that is believed to have been used as a warehouse. This house likely belonged to the commander of the previously discovered military post. Given that the five-foot walls of the house were filled with dirt, researchers believe that it may have been buried intentionally in the third century, just prior to the construction of the walls of Rome in 271 C.E. As works on the subway line are ongoing, the likelihood of future discoveries remains a tantalizing possibility.

While some discoveries take place in the ground, some occur underwater.

Hoard of Roman Coins Found Along the Spanish Coast

In August 2021, two men on a family vacation were snorkeling when they came upon a stash of Roman coins – one of the largest of its kind ever discovered in Europe. The coins, dating back to the 4th-5th centuries C.E., had fallen into a rock crevice 20 feet underwater in Portitxol Bay by Xàbia, a popular tourist resort. The men removed eight coins with a Swiss Army knife and contacted the local authorities once they had inspected their find after surfacing. Authorities returned to the dive site with a team of underwater archaeologists from the University of Alicante and the Spanish Civil Guard. The team ultimately retrieved 53 coins, 3 nails and lead fragments (likely once part of the chest containing the hoard). The coins are in excellent condition, allowing researchers to read their inscriptions and identify the Roman rulers they depict. Rather than being lost in a shipwreck, the coins were probably hidden intentionally by a wealthy landowner to protect them from barbarian invaders during the decline of the Western Roman Empire. The individual most likely sank a boat in the bay with the intention of returning to claim his property but died before doing so. The coins will be restored and exhibited at the Soler Blasco Archaeological and Ethnographic Museum in Xàbia, while the regional government of Valencia is sponsoring further underwater excavations in the area.

Crusader Sword Discovered Off the Coast of Israel

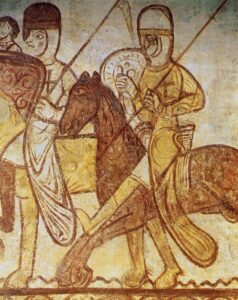

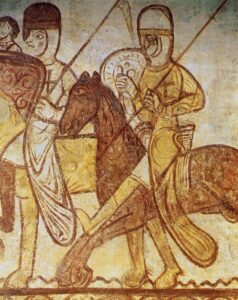

12th Century painting of a Crusader

In October 2021, an amateur diver found a 900-year-old sword dating back to the Crusades off the northern coast of Israel. The sword, as well as other ancient artifacts, became visible after sands shifted on the sea floor. It was covered in seashells, barnacles, and other forms of sea life but is otherwise preserved in perfect condition. The “beautiful and rare find” belonged to a knight, although further restoration is required to identify whether it is of Christian or Muslim origin, as they typically used swords of a similar size and shape. Since the sword was buried in a deep layer of sand and not exposed to oxygen, it avoided rust and other degradation. Archaeologists expect further artifacts to surface, particularly since the site was once a hotbed of mercantile activity. In the meantime, the sword has been taken to a scientific laboratory under the auspices of the Israel Antiquities Authority for cleaning and further research.

We hope you have enjoyed reading about these surprising archaeological discoveries. Amineddoleh & Associates continues to remain invested in the preservation of historical and cultural artifacts. You can access the other entries in our Provenance Series here and read about our firm’s services here.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 29, 2021 |

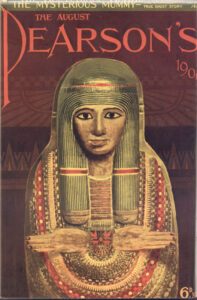

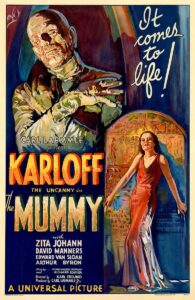

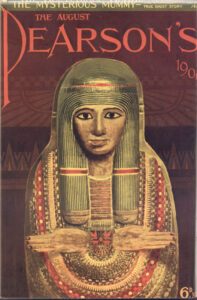

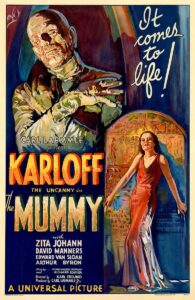

Cover of 1909 Pearson’s Magazine featuring the Unlucky Mummy

Just in time for Halloween, this spooky entry in our Provenance Series explores the strange case of the “Unlucky Mummy,” an ancient Egyptian artifact held by the British Museum since 1889 and rumored to have played a part in several tragic events during the last 150 years. The name of the object is misleading, as it is not an actual mummy, but rather a painted wooden “mummy board” or inner coffin lid depicting a woman of high rank. Mummy boards were placed on top of mummies, covered in plaster, and decorated elaborately with protective symbols of rebirth. The Unlucky Mummy was discovered in Thebes, an ancient hub for religious activity and the site of a renowned necropolis. It dates back to 950-900 B.C.E. While the lid does contain hieroglyphic inscriptions, these only refer to religious phrases; the identity of the deceased remains unknown. In the early 1900s, British Museum specialists believed that she may have been a temple priestess or a member of the royal family, but this was never confirmed by supporting evidence.

According to the museum’s records, the mummy board was originally acquired by an English traveler in Egypt during the 1860s-1870s. The mummy itself was most likely left in Egypt, since it has never formed part of the British Museum’s collection. The traveler was part of a group of Oxford graduates touring Luxor, who drew lots to haggle over the coffin lid. All four companions suffered unfortunate fates soon after this purchase. One of the men disappeared into the desert, one was accidentally shot by a servant and had his arm amputated, one lost his entire life’s savings, and one fell severely ill and was reduced to poverty. The mummy board then passed to the sister of one of the men, Mrs. Warwick Hunt, whose household became plagued by a series of misfortunes. When Mrs. Hunt attempted to have the coffin lid photographed in 1887, the photographer and porter both died, and the man hired to translate the hieroglyphs committed suicide. Clairvoyant Madame Helena Blavatsky allegedly detected an evil influence emanating from the mummy board, and convinced Mrs. Hunt to dispose of the object by donating it to the British Museum. Yet tales of the curse would follow. In 1904, journalist Bertram Fletcher Robinson published an article in the Daily Express titled “A Priestess of Death,” detailing the mummy board’s grisly exploits. When he died suddenly three years later, this was attributed to the Unlucky Mummy’s vengeance from beyond the grave. Even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes and avowed spiritualist, claimed that the mummy’s spirit had used “elemental forces” to strike down Robinson.

One of the more sensational stories is that the mummy board was on the SS Titanic in 1912 and caused the ship to sink. However, this is only a rumor; the Unlucky Mummy has been on public display since the 1890s, except during WWI and WWII when it was placed in storage for safekeeping. It first left the British Museum in 1990 for a temporary exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia, and it made it back to London safe and sound. In fact, much of the mummy’s malevolent backstory was invented by English editor William T. Stead, who possessed a fascination with the supernatural. Ironically, Stead perished on the Titanic – but the Unlucky Mummy’s legacy lives on. It is allegedly responsible for multiple murders, illnesses, injuries, hauntings, eerie noises, flickering lights, and other suspicious activity.

One of the more sensational stories is that the mummy board was on the SS Titanic in 1912 and caused the ship to sink. However, this is only a rumor; the Unlucky Mummy has been on public display since the 1890s, except during WWI and WWII when it was placed in storage for safekeeping. It first left the British Museum in 1990 for a temporary exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia, and it made it back to London safe and sound. In fact, much of the mummy’s malevolent backstory was invented by English editor William T. Stead, who possessed a fascination with the supernatural. Ironically, Stead perished on the Titanic – but the Unlucky Mummy’s legacy lives on. It is allegedly responsible for multiple murders, illnesses, injuries, hauntings, eerie noises, flickering lights, and other suspicious activity.

For those who wish to see the Unlucky Mummy in person, it is currently located in Room 62 of the British Museum. Hopefully, its curse won’t follow you home…

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 26, 2021 |

Today, the Gilbert Trust for the Arts in London announced the return a 4,250-year-old Anatolian gold ewer from the Gilbert Collection to Turkey. The Gilbert Collection was created by Arthur Gilbert (1913-2001), who amassed an outstanding collection of British and European decorative arts that is currently on long-term loan to the Victoria & Albert Museum (the V&A). Unbeknownst to Gilbert, the ewer was the product of illegal excavation and export. This came to light in 2019, after the Gilbert Trust for the Arts, which is responsible for managing the collection, performed an extensive provenance research project revealing the ewer’s connection to an unscrupulous antiquities dealer who concealed its true origins. Our founder, Leila A. Amineddoleh, played a role during this process as she shared her expertise in repatriation matters with the Gilbert Trust’s researchers and provided advice on what approach to adopt (based on legal and ethical grounds).

Today, the Gilbert Trust for the Arts in London announced the return a 4,250-year-old Anatolian gold ewer from the Gilbert Collection to Turkey. The Gilbert Collection was created by Arthur Gilbert (1913-2001), who amassed an outstanding collection of British and European decorative arts that is currently on long-term loan to the Victoria & Albert Museum (the V&A). Unbeknownst to Gilbert, the ewer was the product of illegal excavation and export. This came to light in 2019, after the Gilbert Trust for the Arts, which is responsible for managing the collection, performed an extensive provenance research project revealing the ewer’s connection to an unscrupulous antiquities dealer who concealed its true origins. Our founder, Leila A. Amineddoleh, played a role during this process as she shared her expertise in repatriation matters with the Gilbert Trust’s researchers and provided advice on what approach to adopt (based on legal and ethical grounds).

As a result of its discussions with the Turkish Ministry of Culture, the Gilbert Trust officially donated the ewer to the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara and commissioned a leading contemporary metalsmith to create a piece addressing the object’s history, to be displayed at the V&A in December. This recreation will allow the ewer to remain present in the museum’s galleries and initiate a constructive dialogue on the importance of proactive provenance research, collaboration, and exchange. While other institutions are sometimes wary of repatriating objects without a legal requirement to do so, the Gilbert Trust’s actions demonstrate that it is possible to return cultural objects in a way that is both respectful to current possessors and takes the source country’s wishes into consideration, leading to a mutually beneficial solution.

The Ewer’s Provenance

Not only is the ewer a stunning example of ancient metalwork, it also possesses a fascinating history. This masterpiece was created by a Hattian goldsmith living in Anatolia over 4,000 years ago. The ewer was formed by embossing a single sheet of gold with complex patterns, including an ancient symbol of the sun, in order to accompany a Hattian ruler into the afterlife. When Gilbert acquired the ewer in 1989, he was dazzled by the evocative story as well as its beauty. However, because Gilbert was not very experienced in collecting these types of objects (this was the only archaeological object he ever bought), the seller was able to conceal the ewer’s illicit origins and misrepresent the origins of the piece.

Not only is the ewer a stunning example of ancient metalwork, it also possesses a fascinating history. This masterpiece was created by a Hattian goldsmith living in Anatolia over 4,000 years ago. The ewer was formed by embossing a single sheet of gold with complex patterns, including an ancient symbol of the sun, in order to accompany a Hattian ruler into the afterlife. When Gilbert acquired the ewer in 1989, he was dazzled by the evocative story as well as its beauty. However, because Gilbert was not very experienced in collecting these types of objects (this was the only archaeological object he ever bought), the seller was able to conceal the ewer’s illicit origins and misrepresent the origins of the piece.

In fact, Bruce McNall – the antiquities dealer who sold the work to Gilbert – later admitted to smuggling ancient artifacts out of source countries like Italy, Greece and Turkey. He worked alongside his partner, Robert E. Hecht, to sell items to unsuspecting buyers. McNall is a colorful figure who once owned Thoroughbred racehorses as well as sports teams (the Los Angeles Kings of the National Hockey League and the Toronto Argonauts of the Canadian Football League), enjoying a great deal of commercial success. However, his fall from grace in the early 1990s after defaulting on a $90 million loan resulted in bankruptcy and a 6-year stint in prison. McNall’s autobiography, published in 2003, details his partnership with Hecht and offers a glimpse into the world of illicit antiquities trafficking. According to the book, at one point Hecht occupied the dubious honor of being the world’s largest source of recently discovered antiquities, which he was able to procure thanks to monetary resources and an extensive network of grave robbers, smugglers, and intermediaries. Once items were obtained, they passed through countries without export controls and then onto Hecht, who sold them on to a collector or dealer. In order to sell the illusion that an item’s provenance was above board, Hecht would spin tales about its location in private homes and the like for the past several decades. As his reputation – and notoriety – increased, buyers would come to Hecht knowing that he could procure rare and valuable pieces. This included McNall, who later opened a gallery on Rodeo Drive in Los Angeles supplied mainly by Hecht’s dubious dealings. Both men drove the market for ancient art amongst the wealthy, creating false sales receipts and invoices from foreign-based companies (usually set up by McNall and Hecht) to cover their tracks.

Notably, Hecht was also tied to the Euphronios Krater later returned to Italy by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 2005, Hecht was charged with trafficking in looted antiquities alongside former Getty Museum curator Marion True and Italian dealer Giacomo Medici, but the case was dismissed in Italian court because the statute of limitations expired before the verdict was issued. He moved to Paris in the wake of the scandal, where he eventually passed away in 2012 – although his legacy lives on in the remaining looted objects that passed through his hands and are dispersed throughout the world.

The Importance of Provenance Research

During the period when McNall and Hecht were active, provenance research was not given the same importance it holds today. For the majority of purchasers, including museums, not asking in-depth questions about provenance or looking the other way when confronted with suspicious ownership histories was considered the norm. However, nowadays museums and private collectors increasingly acknowledge the crucial role of provenance research in upholding the legitimacy and ethical role of cultural institutions as stewards for the public.

It is commendable when a collection proactively engages in discussions with foreign entities to right a past wrong. By following this course of action, it is possible for all stakeholders to determine the best outcome for displaced antiquities, without resorting to contentious and costly litigation (an expense that is burdensome for both private institutions and government entities). As such, creative results are possible, as in the Gilbert Trust’s agreement with Turkey. The Gilbert Trust made the decision to engage in proactive discussions with Turkey, a nation known to aggressively protect its cultural heritage and demand the repatriation of looted objects. However, by digging deeper into its collection to understand their histories, the ewer will finally return to its home, the Gilbert Collection will retain its unblemished reputation, and the V&A is engaging the public in discussions concerning ownership, history, and museum ethics.

It is commendable when a collection proactively engages in discussions with foreign entities to right a past wrong. By following this course of action, it is possible for all stakeholders to determine the best outcome for displaced antiquities, without resorting to contentious and costly litigation (an expense that is burdensome for both private institutions and government entities). As such, creative results are possible, as in the Gilbert Trust’s agreement with Turkey. The Gilbert Trust made the decision to engage in proactive discussions with Turkey, a nation known to aggressively protect its cultural heritage and demand the repatriation of looted objects. However, by digging deeper into its collection to understand their histories, the ewer will finally return to its home, the Gilbert Collection will retain its unblemished reputation, and the V&A is engaging the public in discussions concerning ownership, history, and museum ethics.

The Rokeby Venus is Velázquez’s only surviving nude, and it is known to have a mysterious aura with a tendency to incite psychosis in its viewers. Diego Velázquez, a leading artist in King Phillip IV’s court in Spain, is the artist behind the hauntingly beautiful Rokeby Venus. More correctly referred to as The Toilet of Venus, the work goes by the name The Rokeby Venus in many modern descriptions after the English mansion (Rokeby Park) from where it was located from 1813-1906. The work depicts the goddess Venus gazing at a mirror being held by Cupid, who is shown as serving the goddess while she reclines. The hazy, unfocused gaze of the goddess makes it unclear whether Venus is using the mirror to view her own reflection or whether she is staring judgmentally at the viewer. This visual trick serves to both captivate and unnerve the audience, a dynamic that is particularly heightened by the historical origin of the work.

The Rokeby Venus is Velázquez’s only surviving nude, and it is known to have a mysterious aura with a tendency to incite psychosis in its viewers. Diego Velázquez, a leading artist in King Phillip IV’s court in Spain, is the artist behind the hauntingly beautiful Rokeby Venus. More correctly referred to as The Toilet of Venus, the work goes by the name The Rokeby Venus in many modern descriptions after the English mansion (Rokeby Park) from where it was located from 1813-1906. The work depicts the goddess Venus gazing at a mirror being held by Cupid, who is shown as serving the goddess while she reclines. The hazy, unfocused gaze of the goddess makes it unclear whether Venus is using the mirror to view her own reflection or whether she is staring judgmentally at the viewer. This visual trick serves to both captivate and unnerve the audience, a dynamic that is particularly heightened by the historical origin of the work.

One of the more sensational stories is that the mummy board was on the SS Titanic in 1912 and

One of the more sensational stories is that the mummy board was on the SS Titanic in 1912 and

Not only is the ewer a stunning example of ancient metalwork, it also possesses a fascinating history. This masterpiece was created by a Hattian goldsmith living in Anatolia over 4,000 years ago. The ewer was formed by embossing a single sheet of gold with complex patterns, including an ancient symbol of the sun, in order to accompany a Hattian ruler into the afterlife. When Gilbert acquired the ewer in 1989, he was dazzled by the evocative story as well as its beauty. However, because Gilbert was not very experienced in collecting these types of objects (this was the only archaeological object he ever bought), the seller was able to conceal the ewer’s illicit origins and misrepresent the origins of the piece.

Not only is the ewer a stunning example of ancient metalwork, it also possesses a fascinating history. This masterpiece was created by a Hattian goldsmith living in Anatolia over 4,000 years ago. The ewer was formed by embossing a single sheet of gold with complex patterns, including an ancient symbol of the sun, in order to accompany a Hattian ruler into the afterlife. When Gilbert acquired the ewer in 1989, he was dazzled by the evocative story as well as its beauty. However, because Gilbert was not very experienced in collecting these types of objects (this was the only archaeological object he ever bought), the seller was able to conceal the ewer’s illicit origins and misrepresent the origins of the piece. It is commendable when a collection proactively engages in discussions with foreign entities to right a past wrong. By following this course of action, it is possible for all stakeholders to determine the best outcome for displaced antiquities, without resorting to contentious and costly litigation (an expense that is burdensome for both private institutions and government entities). As such, creative results are possible, as in the Gilbert Trust’s agreement with Turkey. The Gilbert Trust made the decision to engage in proactive discussions with Turkey, a nation known to aggressively protect its cultural heritage and demand the repatriation of looted objects. However, by digging deeper into its collection to understand their histories, the ewer will finally return to its home, the Gilbert Collection will retain its unblemished reputation, and the V&A is engaging the public in discussions concerning ownership, history, and museum ethics.

It is commendable when a collection proactively engages in discussions with foreign entities to right a past wrong. By following this course of action, it is possible for all stakeholders to determine the best outcome for displaced antiquities, without resorting to contentious and costly litigation (an expense that is burdensome for both private institutions and government entities). As such, creative results are possible, as in the Gilbert Trust’s agreement with Turkey. The Gilbert Trust made the decision to engage in proactive discussions with Turkey, a nation known to aggressively protect its cultural heritage and demand the repatriation of looted objects. However, by digging deeper into its collection to understand their histories, the ewer will finally return to its home, the Gilbert Collection will retain its unblemished reputation, and the V&A is engaging the public in discussions concerning ownership, history, and museum ethics.