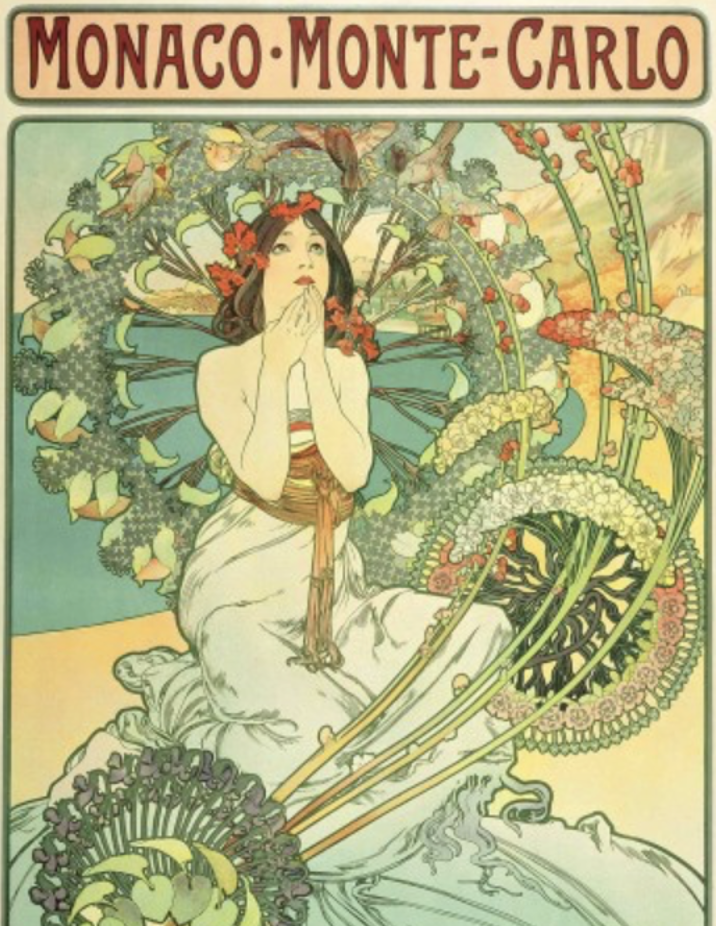

Art Nouveau fans rejoice: July 24th is the late Alphonse Mucha’s birthday. This year’s anniversary comes with a bit less fanfare than his 150th in 2010, when Google created a doodle on the artist’s behalf.

But even without a doodle from Google, Mucha’s legacy continues to influence art and artists around the world. One aspect of his enduring legacy is how his work influenced the rise of celebrity art. This phenomenon has been popping up more and more frequently in American culture, and no one (not even celebrities themselves) are immune from the draw of star power.

Modern Celebrities Embrace Art

No longer playing the role of pirate, actor Johnny Depp has swapped his sword for a paintbrush in real-life. It seems to have been a sound business move. The actor made a staggering $3.6 million selling works from his first “Friends & Heroes” art collection in 2022. His second, entitled “Friends & Heroes II” was released in February. It is comprised of four portraits of artists that have inspired Depp throughout his life: Bob Marley, Health Ledger, River Phoenix, and Hunter S. Thompson. An unbelievable answer to the classic “Dream guests at a dinner party?” question, if ever one existed. Almost already entirely sold out – all that remains on the Castle Fine Art website is a pack of all four prints, priced at a swashbuckling $20,416.67.

Depp’s foray into celebrity art highlights modern culture’s fascination with all-things celebrity. Are Depp’s works prized due to his creative talent as an artist? Or are the pieces selling because they are exclusively of famous celebrities? Or, possibly, Depp is able to sell out faster than Taylor Swift tickets because he, himself, is a celebrity? Which points to the threshold question: when did artists begin to feature celebrities in art? Many art historians look no further than the incredibly gifted Alphonse Mucha, who skyrocketed his own career to greater heights through his collaboration with a famous actress.

Rise of Celebrity Art

“If you have to explain to someone you’re famous, then you’re technically not that famous.”- David Spade.

The beauty of Alphonse Mucha‘s work stems from his deep passion as an artist. Many artists are known for having a lot of gusto, but Mucha really takes the cake. He was master of the Art Nouveau style of art, so masterful in fact that many credit his career for influencing major tenants of the age – politics, religion, philosophy, and – of all things – the career of one very famous actress named Sarah Bernhardt.

Alphonse Mucha, Poster for ‘La Plume’ magazine (1897). Image via muchafoundation.org.

Before we get to Sarah, a little more about our man Mucha. He was born on July 24, 1860, in a quiet town in Moravia. In his youth, Mucha was – in his own words – “preoccupied with observing.” This tendency to notice things around him manifested in a profound artistic talent. Young Mucha could be found making sketches and drawings for friends, family, and fellow townsfolk. His drawings were so prodigious that he collected quite a few fans, even in his early days. One fan was the town’s shopkeeper, who often slipped Mucha free sheets of a paper – a luxury of the day – in order for him to make his creations.

As Mucha grew older, his artistic talent also matured. When he was 18, he was ready to apply to the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. Unfortunately, he was rejected. The admissions office even went as far to suggest he take up a different, “less artistic” career. I’m not sure what they had in mind (medical school?), but fortunately for us, Mucha was not discouraged for long. He decided to simply carry on and continued to make art in whatever way he could.

A year later, Mucha had a bit of luck – an opportunity arose for an artist to work with a Vienna newspaper making advertisements. The pay was pitiful, and Vienna is freezing cold in winter. However, Mucha forged ahead, desperate to create. He applied, scored the gig, and packed his bags for his journey to the big city.

This was a turning point in Mucha’s development as an artist. He spent two years in Vienna, creating advertisements for the paper by day and taking art classes by night. What this did was cement in him a love for creating artwork that was accessible to the average, everyday person. He thrived on creating beauty in pamphlets, posters, and advertisements that most companies and institutions did not have the time or talent to make elaborate. We can start to see, from this period, the development of certain curvature in his lines, and repetition of old world-inspired motifs come up again and again in works that would inevitably become a part of an ordinary person’s daily life.

Mucha retained this love of creating beautiful and accessible work, while still seeking to enhance his skill as an artist through more formal training. Eventually, he applied to – and was accepted to enroll in – the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich in September of 1885. This provided Mucha with formal artistic skills, though it is important to note that Mucha is still believed to be largely self-taught as an artist (which could also mean that he ignored much of what was taught in school). From Munich, he made his way to Paris: the art capital of the world at the time.

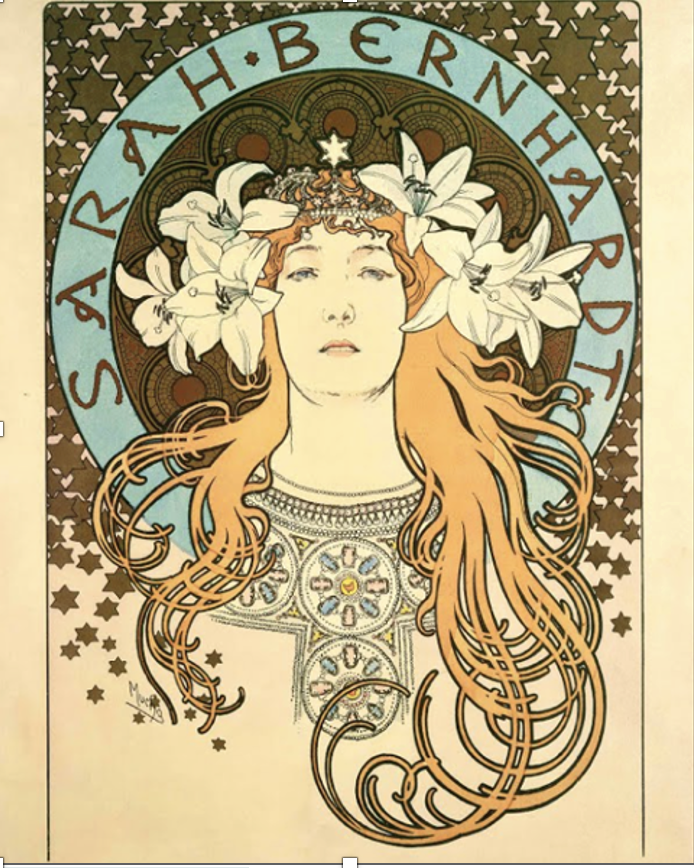

In the City of Lights, he established himself as a “reliable” illustrator (as noted by his biographers). The Paris theater scene is where the lives of Mucha and the phenom Sarah Bernhardt intersect. Sarah Bernhardt is often touted as the original “true superstar.” This is before the current fame-cycle of Hollywood starlets, who now can be seen as a dime a dozen, splashed across the covers of People magazine.

Sarah Bernhardt was the real-deal – a woman with the poise, charisma, and gumption to make a name for herself as an actress against the backdrop of a politically tumultuous city. Not only is she remembered as a strikingly impactful actress, known for her talent, she is also regarded as the first superstar known to personally exploit her own image and likeness for economic gain, and to raise her own fame. This is an important piece of the puzzle of a topic referred to as “publicity,” which we’ll address later.

Mucha began working with Bernhardt in December 1894, in a serendipitous sort of meeting that can only be attributed to fate. Bernhardt’s play, Gismonda, was set to open on January 4th, 1895. On December 26th, 1894 – just a few short days before opening night – the starlet decided that her show needed a new poster to publicize the play. Something dazzling. Something that would leave Paris speechless.

She turned to the manager of a Parisian printing firm for a new poster, pronto. Given the short notice, and the fact that Bernhardt approached the firm in the middle of the Christmas break, Maurice was short on options for the commission. In desperation, he turned to Mucha – truly the only option at hand – and begged him to take on the job. Ever the flexible type, Mucha agreed. And, in doing so, a true collaboration between two legendary artists was born.

The success of Mucha and Bernhardt’s eventual career-long collaboration is likely because the two saw eye-to-eye on Sarah’s talent.

Alphonse Mucha, Poster for ’Gismonda’ (1894). Image via muchafoundation.org.

In other words, Mucha was a fan. In creating the poster for Gismonda, he relied on his personal knowledge of the play itself, as well as his fascination with how Bernhardt depicted the title role. The result? A stunningly ethereal piece that focused the viewer of the poster on the actress herself, rather than on fussy knickknacks in the background. The poster was truly a spotlight on Sarah, in all her glory – and Sarah loved it.

Thus, the two kicked off a mutually beneficial partnership. Bernhardt became Mucha’s artistic muse and mentor in the industry. They also became very good friends. Each seemed impressed by the other’s commitment to creativity, and fervent refusal to be fenced in by artistic norms of the day. Sarah, for her part, pushed the boundaries of Parisian theater by lobbying for politically impactful roles. Mucha, on his end, blazed a trail as a high-end artist for the lower strata of society.

Much of the work Mucha did for Sarah was accessible to the everyday Parisian, because her giant posters were displayed on the street. And, he created many posters of Bernhardt in her various roles throughout the remainder of her career. Because Mucha continued to make Bernhardt the star of each new poster, his work served to elevate her career to even greater heights. In this way, Bernhardt was able to exploit her own image and likeness to increase her status as a public figure – and was one of the first known celebrities to ever do so.

The upside for Mucha was that, because of his work that featured Sarah, he became higher-in-demand as an artist for other jobs. Mucha became more famous and earned more money because he painted someone famous.

Collaboration v. Exploitation

Mucha’s portrayals of Sarah Bernhardt in his artwork were clearly a collaboration. But, using a celebrity’s image in a work of art does bring forth a question: when can an artist legally make use of a person’s image or likeness in a work of art, if use of that image increases the economic value of the work itself?

Modern Legal Framework & Application

To answer this question, two rights come into play. Both come from state, rather than federal law, and are mostly understood through case law.

The first right is called the right of privacy. This means is that private people have the right to prevent the public disclosure of their name and likeness by others. For example, if a company started using a private person’s face as the logo for a brand of salad dressing, that person could bring an action against that company claiming the right of privacy.

The second right, which sounds similar, but functions very differently, is called the right of publicity. That right means that a person has the right to exploit her own image and likeness for her own economic gain. Using the salad dressing example, this is why “Newman’s Own” salad dressing uses his face on the label. His company profits from the use of his public image on its products. The right belongs to Newman’s heirs, because the value of his image is the fruit of his own hard work as a famous actor. (Confusingly, what is referred to as the right of privacy in New York is, in fact, the right of publicity).

Sometimes, the aforementioned rules change if, instead of, as in the example, an advertiser using the celebrity’s image, the person using the celebrity’s image is an artist creating a work of art.

Some courts have held that any work created by an artist, even if it uses a celebrity’s image, is a form of free expression. The First Amendment protects free speech. Included in the many categories of free speech is art – it’s speech, even if it doesn’t make noise.

Courts that have broadly interpreted the First Amendment free speech protection in cases where an artist uses a celebrity’s image in their art have generally permitted it. According to these courts, if artist’s use of the celebrity image is a form of free speech, it is allowed. However, the application of this principle is not as straightforward as it might appear. While some courts have given artists broad discretion under the First Amendment to use celebrities in their works, other courts have sided with celebrity defendants, under the theory that the artist’s work violates the celebrity’s right of publicity.