The Marble Bust found in Texas that will be returned to Germany

Amineddoleh & Associates is proud to announce its role in a recent antiquities matter, whereby a Roman marble bust looted during WWII will be restituted to the Bavarian government in Germany. Below, we share details about the bust’s provenance, examples of other cultural objects looted during World War II, the vital work by experts in establishing provenance, and our role in this important cultural return.

I. HISTORY OF THEFT DURING WWII

Much of the literature about WWII-era looted art focuses on thefts perpetrated by the Nazi Party. The Nazis pillaged on a continental scale – appropriating about 20% of all art in Europe at the time. They were notorious for confiscating artworks they deemed “degenerate,” although other works of art were also swept up in their violent mass seizures. One example is the extensive Czartoryski family collection from Poland, which included Lady with an Ermine by Leonardo da Vinci (later recovered) and a portrait of a young man by Raphael (still missing). After the occupation of Paris in 1940, over 20,000 looted works were taken to the Jeu de Paume gallery, and were kept in a place known as “The Room of the Martyrs.” While Hitler and high-ranking officials had first pick of the loot, German officers could later select masterpieces of their choice. The remainder were slated for destruction, but some evaded this fate thanks to the efforts of art historians and the famed Monuments Men (this title is a misnomer, as this group of British and American members included women).

Looting is often a crime of opportunity, and soldiers on all sides of a conflict may take advantage of the situation by partaking in the appropriation of stolen valuables. Allied soldiers during WWII were no exception. Some of the goods pilfered by Allied troops, like cigarettes and household goods, are relatively inexpensive or nearly worthless by today’s standards. But others – including paintings, rare coins, historic photos, musical instruments, and antiquities – possess great artistic and cultural value. Those valuables continue to be found to this day, sometimes in surprising locations. Some have been returned to the heirs of the original owners while others are involved in ongoing litigation.

Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer

In one instance, a member of the U.S. Army stole a collection of medieval religious objects that had been hidden in a cave for safekeeping during the war. The soldier mailed these priceless artifacts home to his family in Texas. These items, known as the Quedlinburg Treasure, included a jeweled 9th-century manuscript written entirely in gold (the Samuhel Gospel). Decades later, the soldier’s heirs reached an agreement with Germany and returned the items in exchange for $2.75 million. Another case involved a pair of portraits by Albrecht Dürer stolen from a museum in East Germany during the war. These were taken by an American serviceman and later bought by a New York collector, Edward Elicofon, for $450. Although Elicofon was purportedly unaware of the paintings’ provenance, a friend recognized the works from a book on art stolen during WWII. After the museum filed a lawsuit in New York, the court compelled Elicofon to transfer ownership and possession of the works back to Kunstsammlungen zu Weimar (Weimar Art Collection).

Perhaps the best-known case involves Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, known as the Woman in Gold. This gilded painting was forcibly seized by the Nazis after the owners, a Jewish family, were forced to flee Austria in fear of their lives. The portrait is called “the Mona Lisa of Austria.” Along with other works from the Bloch-Bauer’s collection, the portrait wound up in the Austrian State Gallery, but the heirs to the estate fought to recover their family’s lost property. Eventually, after litigation in the U.S. and arbitration in Austria, the Bloch-Bauer heirs succeeded. The dramatic tale became the subject of a film starring Helen Mirren as the main claimant, Maria Altmann, and the painting was later sold in 2006 for $135 million – a record price at the time.

II. AN ART LOVER DISCOVERS THE MARBLE BUST

Not all art and heritage restitutions involve contentious battles. The most recent example of a voluntary return of valuable WWII-looted art can be found in the just-announced agreement between Germany and our client, Laura Young.

The Marble Bust safely strapped in Ms. Young’s car with a seatbelt

Ms. Young happened upon the Marble Bust in the unlikeliest of places: a goodwill thrift shop near her home in Austin, Texas. She purchased the artifact and immediately realized it was more than it appeared to be. The 52-pound Marble Bust, standing at 19 inches tall, was in fact an extremely valuable antiquity. After she drove the Marble Bust home (responsibly strapped into her car with a seatbelt), Ms. Young began digging into its past and discovered the remarkable nature of her find.

Ms. Young later confirmed that, unbeknownst to the goodwill thrift shop owner, the Marble Bust depicts famed Roman commander Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus, known simply as Drusus Germanicus or Drusus the Elder. She went on to discover that the Marble Bust has a significant provenance, including links to royalty.

The Marble Bust’s Provenance

- A Roman Marble Portrait Head of Drusus Germanicus (early 1st century AD)

- Acquired by King Ludwig I of Bavaria (before 1833)

- Exhibited in the Pompejanum, Aschaffenburg, Germany (presumably by 1848)

- Stolen during WWII (1944 or 1945)

- Consigned to a goodwill shop in Austin, Texas (Unknown date)

- Purchased by Laura Young (2018)

- Title transferred to Bayerische Verwaltung der staatlichen Schlösser, Gärten und Seen (the Bavarian Administration of State-Owned Palaces, Gardens and Lakes) (2021)

- Loan to the San Antonio Museum of Art (2022-2023)

A Bit of Roman History

To truly appreciate the richness of the Marble Bust’s provenance, a bit of history is required.

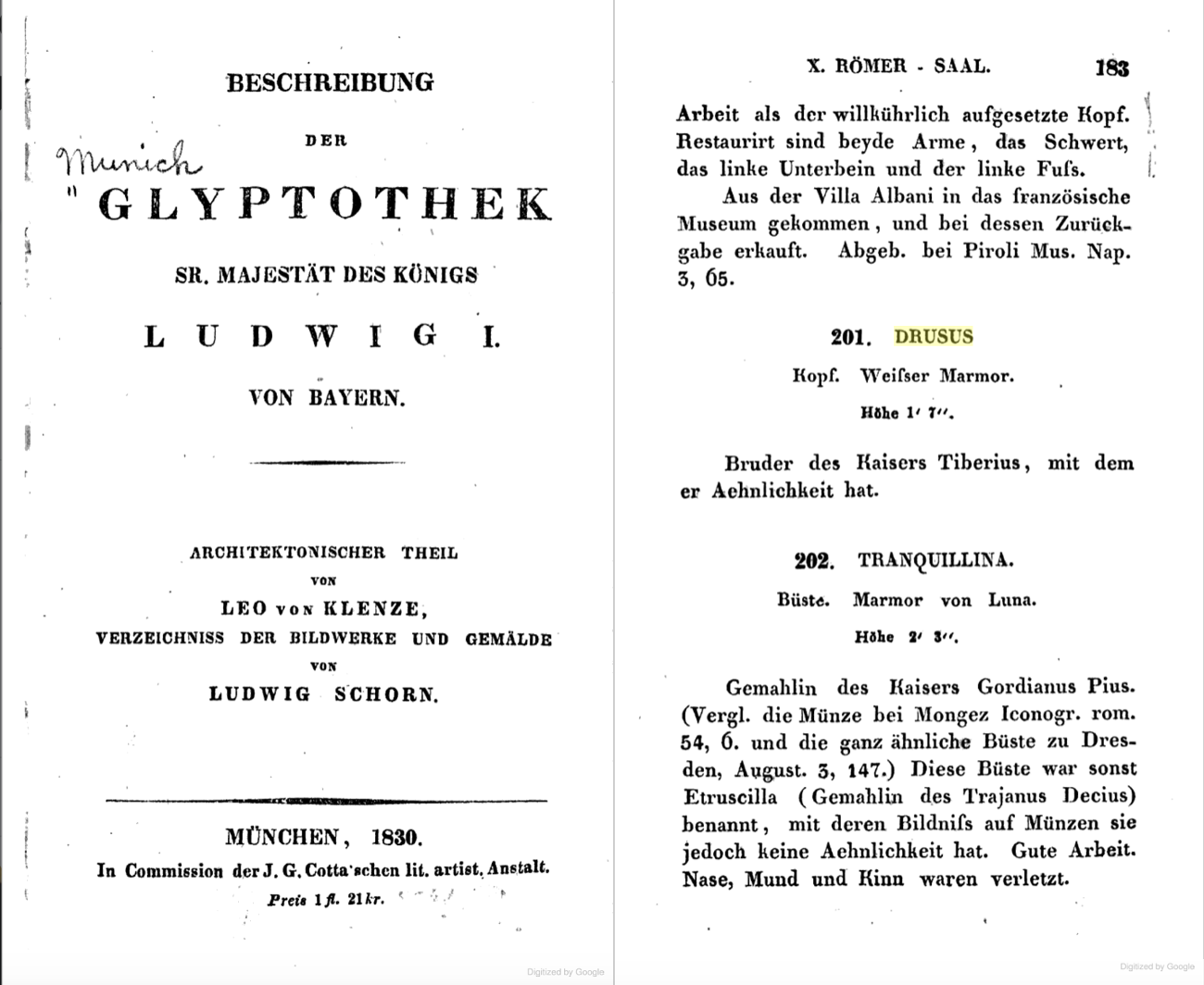

Left, cover of 1833 catalog of King Ludwig I’s antiquities collection , right, description of Drusus (the Marble Head) listed in the catalog

Image from google books digitized version of the catalog

Born on January 14, 38 B.C. to Livia Drusilla and Tiberius Claudius Nero, Drusus Germanicus was the legal stepson of Livia’s second husband, Octavian (later Emperor Augustus and great-nephew of Julius Caesar). Drusus was born shortly after his mother’s divorce, and his mother immediately married Octavian, who historians suspect was Drusus’ true father. Drusus Germanicus eventually became the commander of the Roman forces occupying the German territory between the Rhine and Elbe Rivers. In 9 B.C., Drusus reached the Elbe River, but he was thrown from his horse and died 30 days later from the injuries he sustained. For his conquest of Germania, he received the posthumous honorific title “Germanicus.” The Marble Bust of Drusus Germanicus traveled to Germany nearly two millennia later after its acquisition by the King of Bavaria, Ludwig I, at some point prior to 1833.

Although Drusus was lesser known than some other members of his family, portrait heads of this figure are rare (perhaps due to Drusus’ early death) and highly prized.

Ludwig I and the Pompejanum

After its acquisition by Ludwig I, the Marble Bust was transferred to a most fitting location – the Pompejanum. The Pompejanum (or Pompeiianum) is a replica of a Roman townhouse in Pompeii. Overlooking the Main River in the Bavarian town of Aschaffenburg, the museum was already a popular tourist destination in the 19th century. The Pompejanum was commissioned by Ludwig I, who was inspired, like many cultural enthusiasts, by the excavations at Pompeii.

Ludwig I was both an art lover and a great patron of the arts. During his reign from 1825 through 1848, he commissioned major museums and art projects throughout Bavaria and the rest of Germany in a bid to elevate Munich to the status of rival European art capitals, like Rome and Paris.

His passion for art was first awakened on a trip to Italy from 1804 to 1805. After that trip, the future king became a voracious collector. Much like today’s collectors, he sent agents across Europe to acquire masterpieces. (One of his art dealers, Johann Martin von Wagner, was noted for his unerring eye, scholarly talent, and great commercial aptitude.) With an unlimited amount of money to draw on from his royal coffers, Ludwig I scooped up many highly sought-after pieces. To display his massive collection, Ludwig I commissioned the construction of a number of major museums. One of his first projects was the Glyptothek, which was used to house ancient sculptures. Another, the Staatliche Antikensammlungen (State Collections of Antiquities), was designed in 1848. The works from that institution formed part of the extensive collection of the Bavarian Royal Family.

Ludwig I’s taste in art also ventured beyond the ancient world. In 1836, he created the Alte Pinakothek, the largest museum in the world at the time of its inauguration. Ahead of his time, Ludwig I also established one of the first contemporary art museums in the world–which was unfortunately destroyed by bombing during WWII.

Ludwig I had a deep appreciation for ancient masterpieces and structures evoking the classical era. Projects inspired by this passion include the Propylaea, a monumental city gate constructed as a copy of the Athenian Acropolis and ultimately dedicated as a memorial for Ludwig I’s son Otto, who ascended to the throne of Greece in 1832. It was financed by Ludwig I’s private resources after his abdication, and serves as a symbol of friendship between Greece and Bavaria. While he was still a young crown prince, Ludwig I conceived the project of Walhalla, a temple erected to honor famous Germans. This hall of fame honors nearly 200 laudable people spanning 2,000 years of German history, including both male and female politicians, sovereigns, scientists, and artists, from Albrecht Dürer to Sophie Scholl. Although it is named after the Norse mythological heaven for warriors, the temple was built in the Greek Revival Style and modeled after the Parthenon. The temple continues to be used today, and 19 busts, including one of Albert Einstein, have been added to the collection since WWII.

Pompejanum in Aschaffenburg, Germany, as restored today

© Carole Raddato (owner of Following Hadrian)

Ludwig I also aspired to bring a bit of ancient Rome to Bavaria. As such, he commissioned the Pompejanum, mentioned above, which was constructed between 1840-1848. Designed by architect Friedrich von Gärtner, it was loosely modeled on the House of the Diosuri (Casa dei Dioscuri) in Pompeii. The villa was never intended to be used as a residence; rather, it has always served as a museum. Located near Schloss Johannisburg (one of Ludwig I’s residences), the king could admire it from his window and make frequent visits. Completed with a Mediterranean-style garden and filled with reproductions of mosaics, architectural forms, and artifacts, the king could escape to Italy with just a short trip to the Pompejanum.

Visitors came to the Pompejanum because it was, and perhaps still is, the most accurate reconstruction of a Roman villa in the world. The ground floor features an entrance hall, the guest room, the kitchen, the dining room, and atrium, all organized around two courtyards. The interiors were painted in the Pompeiian fresco style, and the floors feature copies or adaptations of ancient works and Roman mosaics. The collection included Roman marble sculptures, bronze statuettes and glasses, and household items, as well as two god’s thrones made of marble.

Destruction of the Pompejanum

The Pompejanum destroyed after WWII bombings

Sadly, as often happens during conflict, the damage to the museum’s physical structure led to the loss of its collection. The Pompejanum and the surrounding areas were heavily damaged by Allied bombing in 1944 and 1945. Some of the museum’s objects survived bombing only to be looted. But nothing looted from the museum was ever sold by the museum or German government, and thus title to any looted property remained with the Bavarian State. Under U.S. common law principles, valid title to artwork cannot be transferred through looting. There must be a legitimate transaction for title to vest legally in a subsequent purchaser. This means that the Bavarian State continues to maintain a legal claim of ownership over objects that were taken from the Pompejanum.

The Pompejanum Today

The Pompejanum was eventually restored during several phases, the first beginning in 1960. The restoration was completed in 1994, and the villa reopened to visitors that year as the museum of the Bavarian Palace Department and the State Antiquities Collections. Today, it is open to visitors from the spring through the fall.

III. AN ART EXPERT ILLUMINATES THE MARBLE BUST’S PROVENANCE

Establishing the provenance of artwork and antiquities is essential, particularly for objects displaced during times of conflict. It is important not to underestimate the role of art experts in determining provenance, as well as the return and restitution of looted objects. Due to their specialized knowledge and access to resources that are not necessarily available to the public, art experts play a crucial role in establishing the provenance of works and alerting owners to potential red flags. It is always important for purchasers of artwork with unclear provenance or gaps in the chain of ownership to consult experts and ensure that title has been properly transferred.

This pre-war-photo shows the Bust, together with another (today in the Antikensammlungen), standing in the Atrium at the entrance of the Tablinum.

To research her new-found treasure, Ms. Young contacted Sotheby’s. The auction house’s consultant researcher in Ancient Greek and Roman sculpture, Jörg Deterling, identified the subject of the Marble Bust as Drusus Germanicus and alerted Ms. Young that the work had gone missing from the Pompejanum decades ago. Before being looted, the Marble Bust had been displayed in the Atrium, at the entrance of the Tablinum that led to the Pompejanum. Although the exact path of the Marble Bust from Bavaria to Texas is unknown, it is safe to assume that it was looted either by an American serviceman who brought it back to the U.S. or by someone who eventually sold it to an American, likely during WWII or immediately after the end of the conflict.

According to Sotheby’s, Mr. Deterling has been “responsible for many returns, restitutions, and repatriations over the years, but his name has never appeared anywhere in connection with them.” Here, he once again played an instrumental role in the return of a valuable artwork by informing Ms. Young about the historical significance and provenance of her find.

IV. AMINEDDOLEH & ASSOCIATES HELPS MS. YOUNG RESTITUTE THE MARBLE BUST TO GERMANY

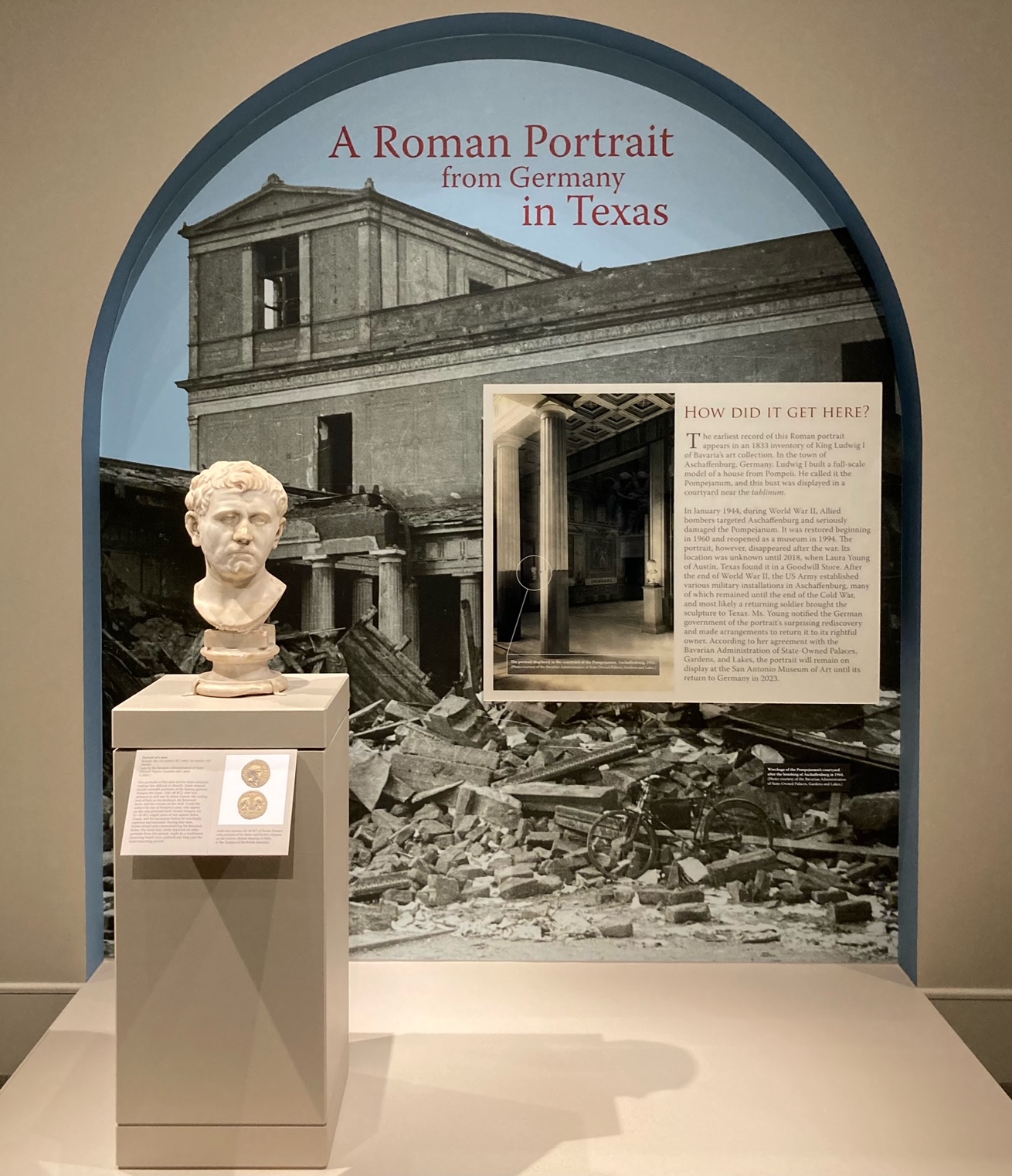

Drusus Germanicus on display at the San Antonio Museum of Art

After being informed of the Marble Bust’s provenance, Ms. Young worked with Amineddoleh & Associates to voluntarily transfer title to Bayerische Verwaltung der staatlichen Schlösser, Gärten und Seen (the Bavarian Administration of State-Owned Palaces, Gardens and Lakes), a government agency in Bavaria, Germany. As part of the restitution agreement, the Bavarian agency committed to loaning the Marble Bust to the San Antonio Museum of Art where it is expected to remain on view until its scheduled return to Germany in 2023.

Rather than sell the Roman bust on the antiquities market, where she could have made hundreds of thousands of dollars, our client instead chose to act ethically and return the bust to its rightful home. We worked with Ms. Young to communicate with German authorities, negotiate the transfer of title, ensure proper acknowledgement of Ms. Young’s actions, and request the work’s temporary display in Texas where its story and our client’s role could be further relayed. The Marble Bust’s journey is an extremely important story to tell. It reflects our passion for the past and collecting, the value of museums in providing access to heritage and knowledge, the unfortunate displacement and destruction of national and cultural heritage during conflict, and the hope that people and institutions will choose to act ethically and protect our shared heritage.

In fact, earlier this week the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston announced the return of a looted marble sculpture to Italy. As in the case with Drusus Germanicus, the object was likely stolen during WWII. The MFA had purchased the antiquity from a Swiss dealer in 1961 for $750. Other records of its whereabouts prior to the purchase are lost, but the dealer had represented that the object originated from Rome. Unfortunately, the MFA’s sculpture had suffered significant damage, such as the loss of facial features, including its nose, mouth and lower left cheek. The Boston museum worked with the Italian Ministry of Culture to effectuate the return of the looted antiquity.

At Amineddoleh & Associates LLC, we are proud to represent clients who value cultural heritage and consult us in matters involving provenance, authentication, ownership, and restitution. In doing so, they help ensure that cultural heritage is protected and safeguarded for current and future generations while being shared with as many people as possible. Thank you to The Art Newspaper for sharing details about this story HERE.