Authenticating artwork can be a complex endeavor at the best of times. Because the value of artwork – both aesthetic and monetary – is subjective, it relies on a complex process involving authentication. In layman’s terms, authentication is ascertaining whether a work is original and can be attributed to a certain artist. However, when an authentication is questioned, this inevitably leads to disputes. There is no shortage of cases involving inauthentic artworks created by forgers (such as Wolfgang Beltracchi and Pei Shen Qian in the infamous Knoedler Gallery scandal), but a rather unique situation arises when artists themselves disavow their work. Can it still be considered authentic in such circumstances? Who is the rightful person to determine the authorship of a work – the themselves, a seller, a buyer, or an expert?

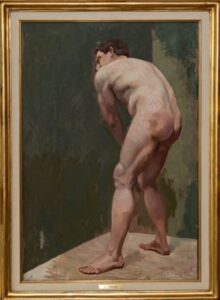

Standing Male Nude, by Lucian Freud

Photograph Courtesy of Thierry Navarro

Lucian Freud’s Standing Male Nude – A Case Study in Authentication and Disavowal

In the case of Lucian Freud, one of the leading English artists of the 20th century, his own denial of a painting was not considered conclusive enough to classify the work as inauthentic. In the mid 1990s, the painting, Standing Male Nude, was purchased by a Swiss art collector. The collector recalls that a few days later, he was contacted by Freud who wanted to repurchase Standing Male Nude, offering him double what he had paid. Upon the collector’s rejection of this offer, the artist became furious and said that unless the collector sold him the work, he would deny having painted it and leave the collector unable to sell. The Freud estate subsequently refused to authenticate the painting, and the collector’s piece languished in limbo for decades.

However, this past November, a team of art experts found definitive evidence confirming what the artist had denied: the painting was, in fact, an original Freud. Scientific tests involved taking pigment samples and using infrared imaging to compare Standing Male Nude with other authentic works by the artist. The work was found to have “an absence of negative indicators for [Freud’s] authorship” by a leading British expert, Dr. Nicholas Eastaugh. These findings were supported by groundbreaking AI technology used by Dr. Carina Popovici at Swiss company Art Recognition. As a result of their own research into the work’s provenance, the collector and private investigator Thierry Navarro believe that the painting was a self-portrait and that Freud was embarrassed by the nude of himself. Although the figure in the portrait is viewed from behind, the facial features appear to match photographs of Freud. Prior to the collector’s acquisition, the painting had hung in a Geneva flat used by fellow artist Francis Bacon at a time when the city served as a “bubble” for the gay community. This helps explain why Freud was so intent on recovering the work.

By creating an authenticity question, the painting’s marketability and resale value was sharply limited. Only works with certificates of authenticity or similar guarantees by living artists will fetch high prices on the legitimate market. Freud’s paintings are worth millions – a lifesize nude of his muse Sue Tilley sold in 2015 for £35.8 million at Christie’s. Previously, another portrait of Sue sold in 2008 for $33.6 million, setting a record at the time for any living artist.

Essentially, authentication can “make or break” the worth of a painting because its attribution is critical. As more and more people view art as an investment and separate asset class, authenticity goes to the core of how the art market operates. But this is not a new phenomenon.

Hahn v. Duveen: The Authentication Case that Rocked the Art World

In 1920, legal disputes concerning art gained worldwide attention when the owner of a painting, believed to be by Leonardo Da Vinci, sued an art dealer who questioned the authenticity of the subject artwork. Dealer Joseph Duveen was one of the world’s best known and successful dealers. Although Duveen had never seen the painting or examined it in person before rendering his opinion, he reasoned that the painting in dispute could not be authentic because the genuine version of the work was in the Louvre. His statement made the painting worthless and unsellable due to the dealer’s sway over other collectors. This case, Hahn v. Duveen, was described as “the world’s most celebrated case of art litigation – a hearsay case with a picture as defendant.” In particular, Duveen was sued for libel; a legal claim that requires the substance of a statement to be false and made with malice.

Clipping from The Illustrated London News of La Belle Ferronière, July 18, 1931 from a Duveen Brothers scrapbook

The court’s opinion criticized the art market and the authentication process: “[a]n expert is no better than his knowledge. His opinion is taken or rejected because he knows or does not know more than one who has not studied a particular subject. . . . Because a man claims to be an expert, that does not make him one.” Hahn v. Duveen, 234 N.Y.S. 185, 190 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1929). Nonetheless, the hold of connoisseurs like Duveen is not so easily dispelled. The market relies heavily on subjectivity when assigning value to works. What makes one artist more valuable than another is not a straightforward matter, and courts in New York (the heart of the global art market) have consistently declined to regulate how the market operates, arguing that it is a matter for participants and experts to decide, as they have the required specialized knowledge. Whether this “hands off” approach is appropriate or not is a question for another day, but it is worth noting that the parties in Hahn v. Duveen settled out of court without a firm attribution in place. Decades later though, Duveen was vindicated when the work sold as a “copy” for $1.5 million in 2011 (likely due to the work’s fame as a result of the litigation).

The situation becomes even more complicated when the person refuting the authenticity of a work is the artist, and not merely someone who “studied a particular work.” How does authentication come into play at such a time?

Authentication as a Three-Legged Stool

In the art market, authentication is often compared to a three-legged stool, which relies on three prongs: forensics, provenance, and connoisseurship. (1) Forensics relies on ever-developing technology to run a myriad of scientific tests on the work. These tests determine certain physical attributes of the painting that can lead to a conclusion supporting its authenticity. However, forgers are also aware of the tests that are run on these works and are able to avoid detection by employing creative methods, such as artificially aging works or using the same pigments as the original artists. (2) Provenance looks at historical evidence tracing the ownership of the work. Ideally, the history of the work can be traced back to the artist without any gaps. (3) The final prong relies on connoisseurs who use their expertise and judgment to determine whether they believe that a work is authentic. This type of evaluation, also known as stylistic analysis, relies on the expert’s “eye” to recognize the artist’s unique style, including the subject matter, brushwork, choice of colors, and composition.

Authentication is established by balancing these three prongs. However, courts, as compared to the art market, tend to weigh these prongs differently. Court prefers the more concrete prongs of forensics and provenance research, whereas the market tends to rely upon connoisseurship. This may cause tension as a court can determine that a work is authentic by weighing the persuasiveness of expert credentials and testimony, but this will not necessarily be reflected in the market. In Greenberg Gallery, Inc. v. Bauman, 817 F.Supp. 167 (D.D.C. 1993), the court sided with plaintiff’s expert Linda Silverman in holding that a mobile sculpture, titled Rio Nero, was an authentic work by Calder, even though Klaus Perls, a renowned Calder expert, identified it as a copy. The court noted that as a trier of fact, it relied on a preponderance of the evidence. However, the art market operates in a very different manner and Perls’ opinion was seen as definitive. The mobile remained unsold for years.

A Lack of Definitive Answers: The Pollock Dilemma

Given that none of these three prongs provide conclusive results, each analysis may lead to contradicting conclusions. As a result,

Jackson Pollock painting. in his studio

Photo by Martha Holmes/The LIFE Premium Collection/Getty Images

many experts may disagree on the attribution of a work. For example, in 2013, the three prongs left the authenticity of a Jackson Pollock unclear. The work in question, a painting titled Red, Black & Silver, was allegedly created by Pollock for his lover Ruth Kligman. The artist’s widow, Lee Krasner, and the Pollock-Krasner Authentication Board disputed the claim. After Kligman’s death, her estate attempted to sell the work at auction in 2012, but it was withdrawn by Phillips so that further research could be performed.

The forensic evidence suggested that the work was done by Pollock. Scientific analysis found a polar bear hair embedded in the painting, which suggested that the painting was authentic since Pollock had a polar bear rug in his studio in 1956, and he was known to lay the paintings on the floor. But the provenance was less cer

tain. While a clear chain of ownership was identified, there was no historical documentation to verify this claim. Lastly, connoisseur Francis V. O’Connor stated that the work does not look like a Pollock. He opines that even if the work was made on Pollock’s estate, it wasn’t necessarily by Pollock’s hand. In this case, as in many others, the three prongs of the ‘three-legged stool’ analysis have resulted in an inconclusive determination as to the authenticity of a work. As a result, this work remains in limbo.

Protecting Expert Opinions: A Legal or Market Concern?

The lack of certainty in the authentication process has led many art experts to hesitate when offering opinions about authenticity. In many instances, art experts have provided their opinions, and their opinions have subsequently been proven wrong. When an art owner is harmed by the opinion of an expert, that owner may decide to sue. This has led many art experts to be hesitant to provide their opinions for fear of facing litigation. As a result, there are fewer connoisseurs providing opinions, thus resulting in a decline in the quality of connoisseurship.

Legal actions taken against authentication boards and experts affect the art market. In Thorne v. Alexander & Louise Calder Foundation, 70 A.D.3d 88 (1st Dept. 2009), the plaintiff sued the Calder Foundation because it declined to authenticate two theatrical stage sets and related materials designed by the artist. The court found that there was no legal basis to compel the foundation to issue an authenticity opinion, even though it would impact the sale price. The Andy Warhol Foundation has also faced its share of lawsuits, with Simon Wheelan v. The Andy Warhol Foundation, 2009 WL 1457177 (SDNY 2009) alleging that the foundation strategically refused to authenticate certain works to drive up the value of others and monopolize the market. While this case was ultimately withdrawn, it calls into question how experts are regulated to ensure good faith when issuing opinions.

Experts can face liability for incorrect opinions, even those given in good faith, under the theory of tort negligence, in addition to legal costs associated with defending themselves. A flurry of lawsuits culminated with Keith Haring Foundation disbanding its Authentication Committee in 2012. As a result, authenticators are not providing opinions, which is negatively affecting the art market. In response, a bill was introduced in the New York State Legislature in the spring of 2014. This bill, which would amend the New York Arts and Cultural Affairs Law, would protect art authenticators from “frivo

lous or malicious suits brought by art owners.” Authenticators are defined as individuals and entities “recognized in the visual arts community as having expertise regarding the artist” when rendering an opinion. A modified version of the bill was passed in 2015, but it remains to be seen whether this will provide a robust shield for art experts issuing authenticity opinions.

Moral Rights Legislation – a Shield or a Sword for Artists?

In many instances, artists are victims of the art market’s subjectivity when determining authenticity. For example, in Herstand Co. v. Gallery, 211 A.D.2d 77, (N.Y. App. Div. 1995), Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, a Polish-French modern artist known as Balthus, declared and signed that a drawing was not authentic. Despite Balthus’ confirmation, the court ruled in favor of the gallery selling the artwork, choosing to believe an expert’s testimony of authenticity over the artist’s own actions.

However, visual artists possess legal rights that can protect them and their works. Most countries have a moral rights system allowing an artist to protect their personal and reputational rights, in addition to their economic rights (such as copyright). For example, many countries grant artists the right to not have a work falsely attributed to them and to protect their honor and reputation with respect to their works.

In the United States, some of these rights have been codified in the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA). VARA is more limited than international art law, or the moral rights of other countries, such as France. Under VARA, an artist’s rights are limited to their lifetime and cannot be assigned or transferred. But VARA grants artists two overarching rights with respect to their authorship. First, artists have a right of attribution, so that an artist is recognized for works they create and are not associated with those that they did not create. Second, artists have a right of integrity to protect their reputation, such that they can disavow works that have been damaged, altered, or mutilated.

However, as seen in the case of Freud’s rejection of Standing Male Nude, artists can also create uncertainty and manipulate the authentication of their works for their own personal reasons.

Cowboys Milking, 1990, Cady Noland

Another artist, Cady Noland, disowned her work, rather than rejecting it outright. This occurred with two different works that were damaged or not properly stored and preserved. Her 1990 silkscreen on aluminum, Cowboys Milking, went up for auction at Sotheby’s but upon Noland’s inspection, she noticed that the corners of the aluminum were damaged. Similarly, Janssen Gallery stored Noland’s sculpture, Log Cabin (1990), improperly and the gallery restored the work without Noland’s consent. In each instance, Noland disowned the work, arguing that if the work were to be auctioned off with her name attached, it would prejudice her honor and reputation. Noland’s rejection of two sculptures spurred lawsuits from the owners, who were no longer able to sell the works for their full value.

Elyn Zimmerman, known for her large scale art sculpture installations, also rejected two projects from her list of works. In one instance, the work was not installed consistent with her design, and the contractor left a large hole in the sculpture. Zimmerman said that the work was past salvaging, and so decided not to put her name on the piece. Both Zimmerman and Noland exemplify ways in which some artists rely upon their reputational rights to remove any unwanted attributions.

Other artists simply reject any association with works so that they can assert control over their oeuvre.

Richard Prince is well-known today for his appropriations of advertisements and other popular images. However, before he gained acclaim in the 1980s, he had explored a variety of different mediums including paintings, drawings, collages, and etchings. In a 1988 interview with Flash Art magazine, Prince said he destroyed 500 of his early works. Prince said that he ripped up the works that he did not like from the mid to late 1970s and put them in garbage bags. However, several works from that period were already sold and were beyond his reach. Prince has claimed that these works no longer represent him as an artist. Over the years, Prince has taken several steps to disavow his early work and re-create his oeuvre beginning in the 1980s. On Prince’s website, his biography omits any exhibitions of his work before 1980, creating the public impression that his career began in that year. He also relied upon the copyright to his art, refusing any reproductions of these early works to be printed in books or catalogues. When a museum exhibited his early work, he refused to participate or grant the museum any rights for images or reproduction. Generally, major museums have followed Prince’s example; both the Guggenheim and Whitney Museums have only acknowledged and exhibited works from or after 1980 in their retrospectives of Prince.

Gerhard Richter in his studio with his paintings on the wall, February 1962.

Copyright and Photo by: Gerhard Richter 2020 Courtesy of the artist and the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Gerhard Richter, a German artist whose works have sold for record prices, remains in strict control of his catalogue raisonné to this day. Over the years, Richter has become an artist known for revising and editing his oeuvre. He has removed works from catalogues and rejected paintings from his early West German period. During this period, between 1962 and 1968, Richter went through a stylistic evolution in which he experimented with a figurative style. These realistic paintings varied greatly from his later abstract and photo-realist paintings. Richter’s revisions of the historical catalogues has sparked controversy. As the artist and creator of the paintings, he has a right to define his own body of work. Yet, using this right to modify these historical catalogues can create disputes and distrust in their historical accuracy, and rejecting works offhand can manipulate the market and the resale of works disowned by the artist.

Another famous artist, Pablo Picasso, famously said “I often paint fakes.” This statement questions the art market and the authentication of works but also causes problems for buyers. This was also reflected when Picasso rejected a painting later confirmed to be his original work. When he was handed a photograph of Erotic Scene (La Douceur), he said it was not his work, but just a “bad joke by friends”. The painting, gifted to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1982, sat in storage for several decades. In 2010, the Met prepared for a Picasso show and was faced with authenticity issues concerning the work. The museum ultimately confirmed that the painting was authentic despite Picasso’s statement.

Pest Control Logo

Photo from Pest Control website

As the art market has developed and the complexity of authentication leads to legal controversy and disruption, living contemporary artists have taken authentication into their own hands. Banksy has put a system in place that allows him to be the only authority on the authenticity of his work. This control is in part a by-product of his anonymity. In 2008, Banksy established Pest Control to serve as the sole authenticator of his works. Any Banksy sold after 2009 will be accompanied by a certificate of authenticity (COA) issued by Pest Control and they will retroactively issue COAs for any pre-2008 works they deem authentic. Establishing a third-party authenticator like Pest Control protects the artist’s rights, but it can also influence the market. As seen above, the artist does not always have the final say in the authentication of their works. Pest Control, however, has allowed Banksy to do so. In 2008, five works came up for auction at Lyon & Turnbull in London, and Banksy refused to authenticate them. Pest Control rejected the works’ authenticity and encouraged buyers to boycott the sale. As a result, none of the works were sold. Pest Control has given Banksy access to the art market, allowing him to control what is included in his body of work and sell his work without interference from, or reliance upon, the uncertainty of the three authentication prongs.

As exemplified by Noland, Zimmerman, Prince, Richter, and Picasso, artists have moral rights, and some artists exercise them once their art is on the market. Some artists rely on these rights to protect their work and reputation, others use them to subvert the art market, while others simply wish to remove or disassociate themselves from works they feel are inferior or not representative of their artistic vision and image. While the protection of authors’ rights is important, some question whether artists are abusing their power without considering the larger effects on the market. On the other hand, it may be argued that as the creators of artistic works, artists are in the best position to determine what should or should not be included in their body of work. While this may cause consternation for collectors seeking to resell artworks, there may be limited recourse.

Conclusion

Authentication and attribution is a tricky business. Even after centuries of the art market operating in more or less the same way – responding to supply and demand as well as subjective appraisal – there is still no magic formula to establish whether a work is authentic. Forensic and scientific analysis, combined with a work’s provenance, may provide evidence in support of authentication, but in the absence of a clear link to the artist, collectors risk works being called into question at a later date. Even if an artist is alive at the time the work is sold, there is no guarantee that he or she will wish to remain associated with it. This is why artists and collectors, no matter how new or experienced, should consult with reputable legal counsel to be aware of their rights and risks when engaging in art transactions.