Like other nations rich in archaeological material, Mexico has suffered a great deal of looting and illegal export of its cultural heritage over the past decades. Despite enacting protective legislation dating back to the late 19th century, cultural heritage objects from Mexico continue to be smuggled out of the country and sold on the open market. These items, many of which hail from pre-Columbian indigenous societies such as the Maya and Aztec, are highly prized by museums and private collectors alike. Stelae (free-standing commemorative monuments erected in front of pyramids or temples and made from limestone), polychrome vessels, jade and gold funerary masks, stone altars, and sculptured figurines are among the many types of objects offered for sale. This is a profitable business worldwide; according to Sotheby’s, its auctions of these items have reached nearly $45 million over the past 15 years. (One of our previous blog posts details the theft of pre-Columbian antiquities worth over $20 million from Mexico’s National Museum of Archaeology on Christmas Day 1985, and how authorities recovered them 3 years later.)

Pre-Colombian Stelea

Photo Credit: National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.

In light of these circumstances, Mexico has recently taken several concrete steps to strengthen efforts to track down and recover cultural and historical artifacts. In 2011, the National Institute for Anthropology and History (NIAH) announced the launch of a new unified database for cultural property, which allows for the inscription of cultural goods from anywhere within Mexico. Each item in the database is provided with a unique ID number and accompanying details (such as type, material, dimensions, and provenance), resulting in a publicly accessible and standardized system. This is an invaluable tool that will aid the government in protecting the country’s approximately 2 million movable artifacts.

Mexico has also implemented measures to further protect heritage items already removed from within its borders. In March 2013, the governments of Mexico, Guatemala, Costa Rica, and Peru contested the sale of pre-Columbian art from the Barbier-Mueller Museum at Sotheby’s Paris. All these countries have similar laws vesting ownership of antiquities in the State; therefore, they alleged that the sale was illegal because the objects were not accompanied by export licenses or sufficient provenance information confirming that the works were removed prior to the passage of the relevant laws. Nonetheless, the sale went ahead as planned. A French diplomat stated that the items did not appear on the Interpol database or ICOM Red List, and as such were not considered looted or stolen. (This statement was made even though pre-Columbian antiquities are underrepresented on both lists.) Ultimately, nearly half of the lots failed to sell, and the total sales proceeds fell far below the pre-sale estimate. Public pressure may have played a role in staving off bidders.

Despite this controversy, auctions of similar items have continued. In September 2019, Mexico and Guatemala jointly denounced the auction of pre-Columbian artifacts at French auction house Drouot. The auction house claimed the sale was “perfectly legitimate” and proceeded to sell 93% of the lots, netting $1.3 million for the sale. In response, the consigner, Alexandre Millon, stated that he was a victim of “opportunistic cultural nationalism.” This stoked further tension among countries of origin and market countries.

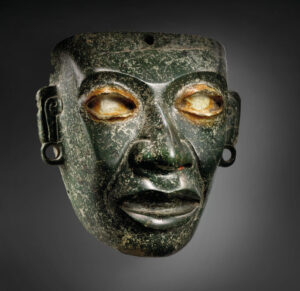

Teotihuacan mask, ca. 450–650

Photo Credit: Christie’s

In February 2021, NIAH lodged a formal legal claim against Christie’s over the sale of 33 pre-Columbian objects, including a stone sculpture of the goddess of fertility Cihuatéotl estimated at $722,000-$1.08 million and a Teotihuacán green stone mask of Quetzalcóatl estimated at $420,000-$662,000. Notably, the mask previously belonged to French dealer Pierre Matisse, son of artist Henri Matisse. While Christie’s maintained that it was confident in the legitimate provenance of the items, historian and archaeologist Daniel Salinas Córdova indicated that the circumstances under which the items had left their places of origin was still unclear. He reiterated that auctioning pre-Columbian antiquities is dangerous because it “promote[s] the commercialization and privatization of cultural heritage, prevent[s] the study, enjoyment, and dissemination of the artifacts, and promote[s] archaeological looting.” Although the sale proceeded and the legal claim has not yet been resolved, Mexico continues to enforce its patrimonial rights.

In September 2021, ambassadors from 8 Latin American Countries (Mexico, Bolivia, Costa Rica, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Panama, and Peru) banded together to stop an auction of pre-Columbian artifacts in Germany. Mexican Secretary of Culture Alejandra Faustro sent a letter to the Munich-based dealer, Gerhard Hirsch Nachfolger, citing Mexico’s 1934 patrimony law and reiterating the government’s commitment to recovering its cultural heritage. Mexico’s ambassador to Germany, Francisco Quiroga, even visited the auction house in person in an attempt to block the sale. A complaint was also filed with the Attorney General’s Office in Mexico. The auction took place, but of the 67 pieces identified as being Mexican, only 36 sold. Notably, one of the highlights – an Olmec mask with an estimate of €100,000 – did not achieve the reserve price.

That same month, Mexico announced the creation of a new team composed of National Guard personnel tasked with the recovery of stolen archaeological pieces and historical documents. The nation’s president, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, credited Italy with the idea. He stated, “Italy has a special body to recover stolen archaeological pieces. We are going to follow that example, I have given the instruction for the National Guard to constitute a special team for the purpose,” Lopez Obrador said.

As recently as November 2021, the Mexican government issued a letter questioning the legality of two auctions in Paris (at Artcurial and Christie’s) selling pre-Columbian objects. Embassy officials and the Mexican Secretary of Culture asked for the sales to be halted on the grounds that they “stri[p] these invaluable objects of their cultural, historical and symbolic essence, turning them into commodities or curiosities by separating them from the anthropological environment from which they come.” Only a few months earlier (in July), the governments of Mexico and France had signed a Declaration of Intent on the Strengthening of Cooperation against Illicit Trafficking in Cultural Property, which was meant to signal a recommitment towards the restitution and protection of each nation’s cultural heritage. Although Mexican officials appealed to UNESCO, bidding opened as scheduled on Artcurial’s online platform (with lots priced at $231-$11,600) and Christie’s earned over $3.5 million in its own sale. The day before the Christie’s sale, the embassies of Mexico, Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, and Peru in France issued a joint statement decrying the “commercialization of cultural property” and “the devastation of the history and identity of the peoples that the illicit trade of cultural property entails.”

Nonetheless, Mexico’s persistence has borne fruit. In September 2021, it was able to halt the sale of 17 artifacts at a Rome-based auction house. The Carabinieri TPC seized the objects after an inspection revealed that they had been illegally exported, and returned them to Mexico in October. The successful recovery of these objects demonstrates the importance of international cooperation. Many governments’ resources are stretched thin policing their own borders for cultural heritage smuggling and theft, and therefore greatly benefit from assistance by foreign law enforcement. It is also an example of how successful cultural diplomacy can be in the recovery of such objects.

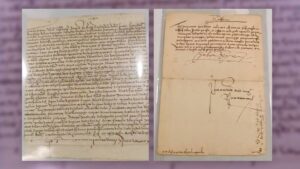

The letter signed by Hernán Cortés recovered by the Mexican authorities.

Photo Credit: The National Archives

In addition to law enforcement and government agencies, laypeople have a crucial part to play in the recovery of looted or illegally exported artifacts. For instance, a group of academics in Mexico and Spain helped thwart the sale of a 500-year-old letter linked to conquistador Hernán Cortés. The letter, dating back to 1521, had been offered for sale by Swann Galleries in New York in September 2021. It was expected to fetch $20,000-$30,000. By searching online catalogues of global auction houses and a personal trove of photographs depicting Spanish colonial documents, the group traced the letter’s provenance to the National Archive of Mexico (NAM), a UNESCO World Heritage Site. An image of the letter had been taken by a Mormon genealogy project, which provided supporting evidence. Furthermore, the group unearthed 9 additional documents linked to Cortés that had been sold at auction – including at Bonhams and Christie’s – between 2017 and 2020. One of these had been sold previously at Swann Galleries for $32,500 and later displayed at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York as part of an exhibition. It was confirmed that all the documents had been stolen from the NAM – they were surgically excised from books – and illegally exported. In response, Swann Galleries cancelled the planned auction. The purchaser of the aforementioned letter returned it in good faith to the auction house. Mexico’s Foreign Ministry enlisted the help of the US Department of Justice to repatriate the 10 manuscripts, in cooperation with the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office and Homeland Security Investigations. The manuscripts were formally handed over in September 2021.